|

Journal Transcends Time

Civil War Writings Touch Nassau Woman

By Derek L. Kinner

Georgia/Florida Times-Union Staff Writer

Photos by M. Jack Luedke / Staff.

February 23, 1997

Reprinted here by permission of the Florida Times-Union. Unauthorized

copies of this article are prohibited.

Fernandina Beach, Fla. – The journal

was buried in a box in a roadside vendor's makeshift flea market when

Robin Cross discovered it 18 years ago. Fernandina Beach, Fla. – The journal

was buried in a box in a roadside vendor's makeshift flea market when

Robin Cross discovered it 18 years ago.

Being a self-professed "book nut," Cross said she decided to buy the

book from the Nassau County flea market. She said she had no idea the

effect it would have on her life.

In the years since, the journal has formed a bond between

Cross and a

St. Marys woman she'll never know, a woman who was in her late 20's as the

Civil War raged through the United States. But Cross has learned a lot

about the history of the times from her occasional readings of the journal

and its newspaper clippings.

She also has learned a lot about Maria O. Bessent, the woman who put it

together.

"She's like a song that I hear in my head,"

Cross said of Bessent.

"She's like a melody dancing through time."

Looking back on her discovery of the journal, Cross said it was fate

that made her come upon it.

"I think Maria found me," Cross said.

The journal's find began a journey of information. Over the years,

Cross would pull out the journal during quiet times and read different

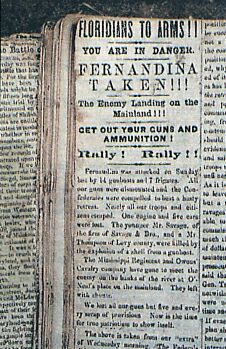

news clippings and entries. There were newspaper stories about a fire in

Jacksonville, war battles and obituaries.

"I was intrigued, of course," Cross says. "I had a full-time job and a

busy family, so I could only read it at times and then lay it aside."

"Though she learned a lot from the journal, the information that most

eluded Cross was Bessent's biographical history.

"I could not find any answers," she said. "I spoke to hundreds of

people but nobody knew who Maria Bessent was."

Then early last year, Cross found an entry that mentioned White Oak

Plantation. She called the plantation's archivist and learned that an

Abraham Bessent purchased the plantation in 1842.

The Bessents were a family of shopkeepers from St. Marys, and the

journal Cross had purchased was initially used as an account ledger of

sorts.

Cross

said the ledger was closed in 1854 and Maria Bessent began using it as a

scrapbook for articles. From poring over public records in Camden County,

Cross determined that Bessent family was a well-to-do family, which

afforded Bessent the luxury to pursue writing and not marry until she was

35. Cross

said the ledger was closed in 1854 and Maria Bessent began using it as a

scrapbook for articles. From poring over public records in Camden County,

Cross determined that Bessent family was a well-to-do family, which

afforded Bessent the luxury to pursue writing and not marry until she was

35.

When Bessent did marry, it was to Samuel

Burns, an Irish immigrant. Because they married outside the county,

Cross could only guess that the

approximate date would have been about 1873.

In 1874, Burns and his new wife purchased White Oak from Nassau County

commissioners. Cross said she had never found out how the county came to

own the property, but speculates it was put in receivership to pay Abraham

Bessent's back taxes.

Bessent and her husband ran White Oak as a 2,850-acre rice plantation.

Burns died in 1888 and his widow continued to run the plantation herself

until she sold it in 1893 for $1 to E.N. Stone. Cross said she has not

found any explanation for the sale.

Bessent then moved back to St. Marys, where she lived until she died in

July 1923 at the age of 91, Cross said.

Cross said her search's high point came earlier this month after a

discussion with a museum employee in Camden County who told Cross that

many Bessents were buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in St. Marys.

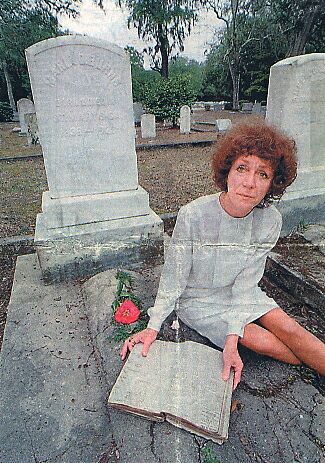

On Feb. 13, Cross and a friend drove up to St. Marys in the rain and

searched the cemetery for Bessent's headstone.

They found Bessent's grave and memorial about 20 feet away from her

husband, who is buried next to his first wife and children. Cross said

that before Maria Bessent married Burns, they had been neighbors.

"In death and in life, they are neighbors,"

Cross said.

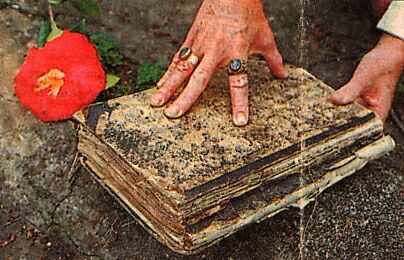

Cross

said just keeping the journal has been a miracle. She nearly lost it in a

fire in 1988, when the flames grew so hot they melted her brass bed. The

journal, one of the few things salvageable, was kept in a wooden box under

her bed and wasn't harmed. She also kept the journal with her during the

many years she lived on a a boat. Cross

said just keeping the journal has been a miracle. She nearly lost it in a

fire in 1988, when the flames grew so hot they melted her brass bed. The

journal, one of the few things salvageable, was kept in a wooden box under

her bed and wasn't harmed. She also kept the journal with her during the

many years she lived on a a boat.

Now 52 and a grandmother, Cross has a little more time to pursue the

story of Bessent's life. She said that March 1 will mark the 133rd

anniversary of the day Maria Bessent closed the journal.

"I'm attached to Maria," Cross says. "It's like the continuity of

intangibles over time. It's a quirk that I found it at all. Certainly,

it's a quirk that it survived the fire.

"On special evenings, I take out the book and look at it and wonder." |