|

EARLY DAYS OF

COASTAL GEORGIA

Photographs by

ORRIN SAGE WIGTHMAN

M.D., F.R.P.S., HON. P.S.A.

Story by

MARGARET DAVIS

CATE

Author of “Our Todays and Yesterdays”

Fort

Frederica Association, Publisher

St. Simons Island, Georgia

University of Georgia Press, Distributor

[Photos

colorized by Amy Lyn Hedrick using MyHeritage.com's

colorization tool]

Pg. 1

You may wonder why a collection of

pictures was made of Coastal Georgia scenes. It happened this way.

About 1936,

Margaret Davis Cate and I decided

that, as many of the historic landmarks were fast disappearing, it

was more or less a duty for her, as a historian, and for me, as a

photographer, to take this opportunity of preserving them for

posterity.

The tabby houses of two hundred years ago were falling

to pieces. The slave cabins were disintegrating, roofs had fallen

in, doorways were gone. But the land remained and in the cemeteries

we found the history of the early settlers. Also, we were able to

reach the home life of the Negroes, seeing them on the little plots

of land they owned and in their native environment—unspoiled and

natural. They were a lovable people, earnest, honest, and perfectly

happy in their surroundings. We have tried to preserve in

photographs and sketches the charm of these people, who are direct

descendants of the slaves of early times and retain the

characteristics of their forebears. They all tell a story—one which

we do not want to lose.

Mrs. Cate, who is familiar with the life and

character of the southern Negro, has been able to capture the spirit

of the times as no other person could possibly do it, as she had not

only the friendship but the confidence of these people.

We hope this book will fulfill the object for which it

was assembled.

ORRIN SAGE WIGHTMAN, M.D., F.R.P.S.,

HON. P.S.A.

Pg. 2

Dr. Wightman’s wonderful

pictures record for us visible evidence of our Coastal Culture. The

Military Era and the Plantation Era belong to history. Each had its

story and each produced its heroes. Oglethorpe and the

soldiers of Bloody Marsh will never be forgotten as they give life

and color to the Military Era. Neither should we forget the

Plantation Era which produced a Corbin and a Neptune.

Gone are the tabby walls and the way of life lived within these

walls.

In writing these stories to interpret

Dr. Wightman’s

pictures, all the knowledge gained in a lifetime of research was

used. For the scores for persons who have assisted in this study

throughout these years grateful appreciation is expressed.

However, especial acknowledgment is due to

Miss A.

Jane Macon; Miss Catherine Clark; Miss Ophelia Dent; Mrs.

Ruby Wilson Berrie: Miss Mary L. Ross; Mr. Richard A. Everett; Mrs.

Maude G. Lambright; Mrs. Mary Givens Bryan, Director of the

Georgia Department of Archives; Mrs. Lilla M. Hawes, Director

of the Georgia Historical Society; and to the Manuscripts Divisions

of the Libraries of the University of Georgia and Duke University,

and the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North

Carolina.

Pg. 3

This book is dedicated

by the authors to

ALFRED WILLIAM JONES

in appreciation of his work

in preserving the history

and traditions of the

EARLY DAYS OF COASTAL GEORGIA

Pg. 5

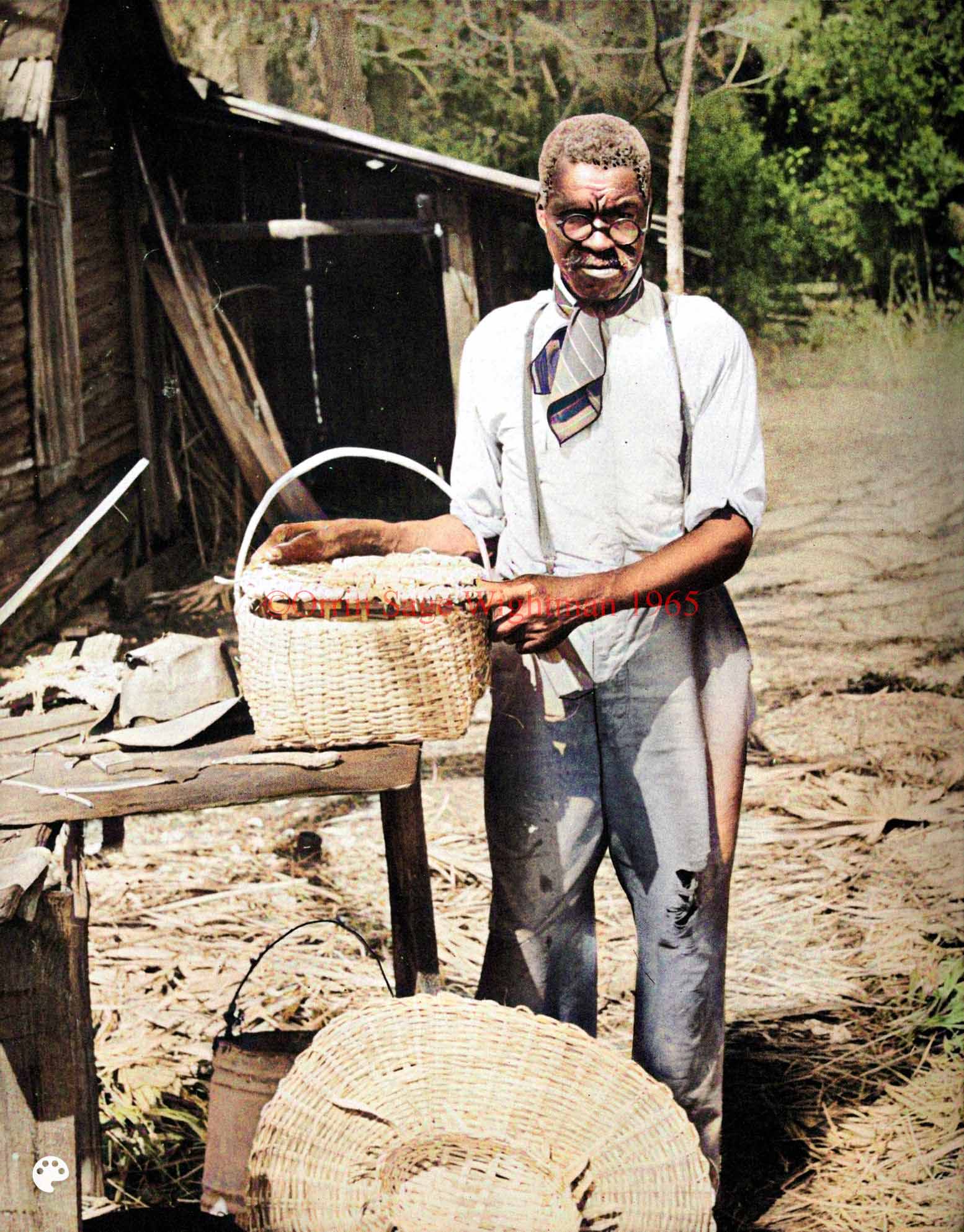

| Charles Wilson |

159 |

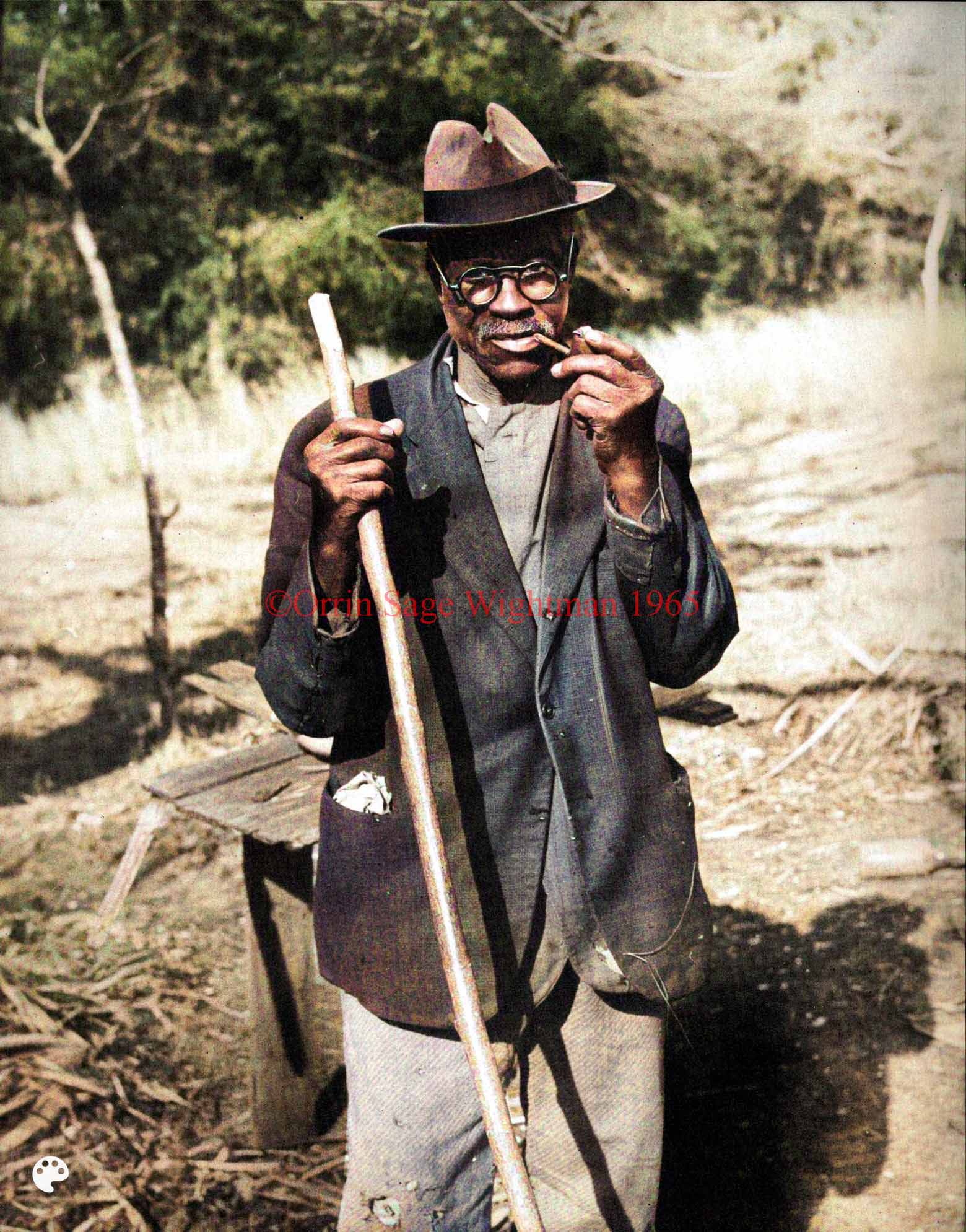

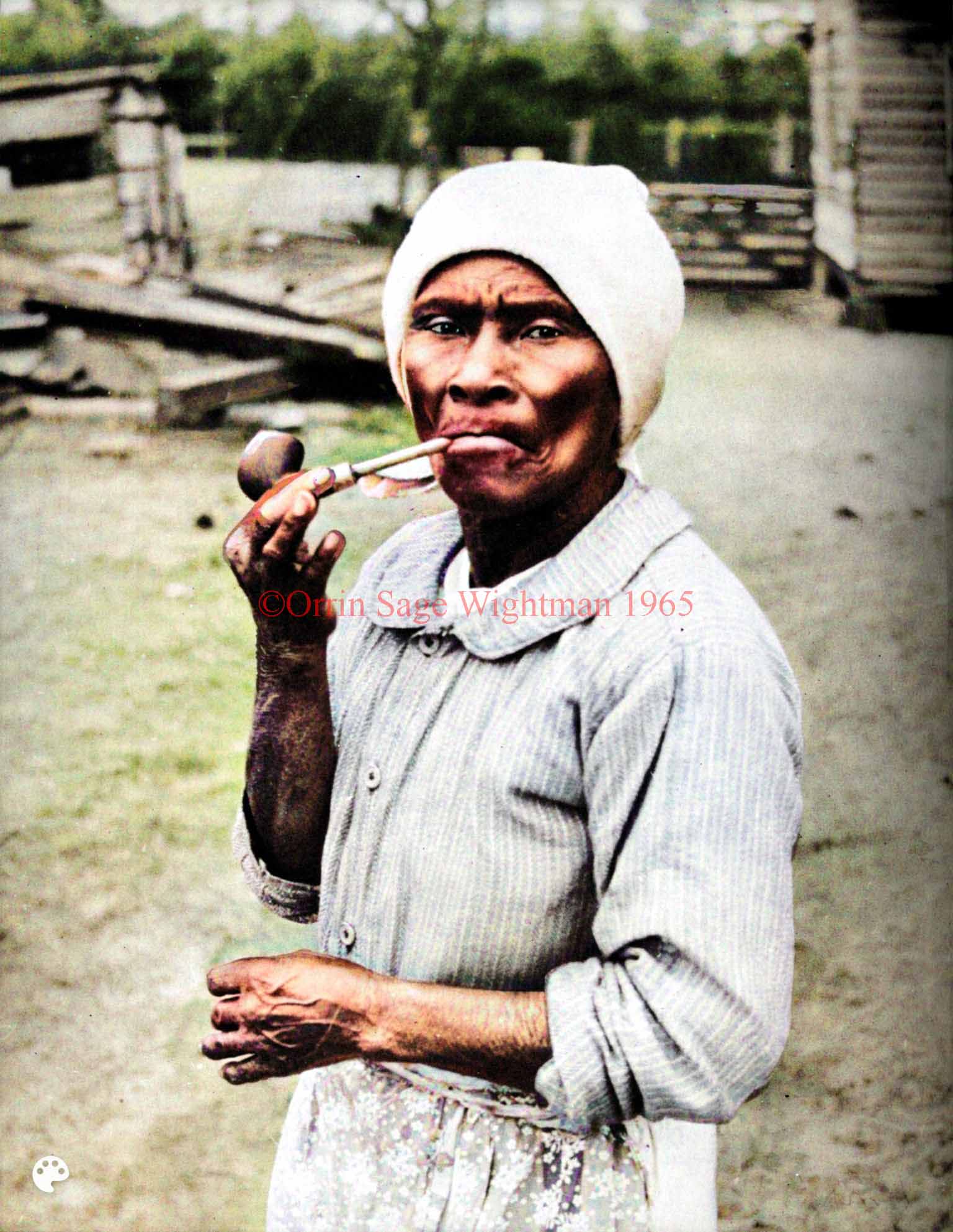

| Charles Wilson & his pipe |

161 |

| Charles Wilson & his horseshoe |

163 |

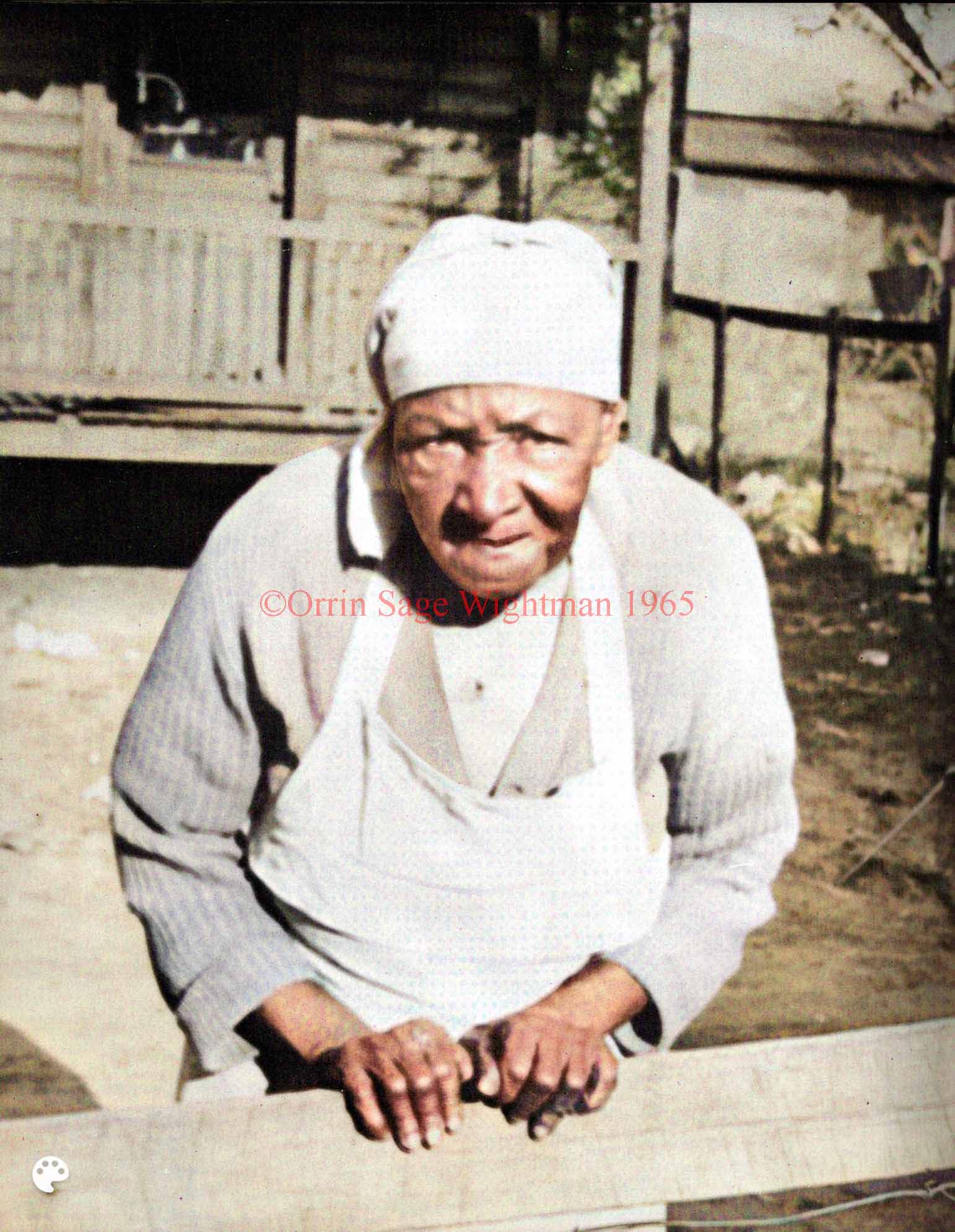

| Mary Williams |

165 |

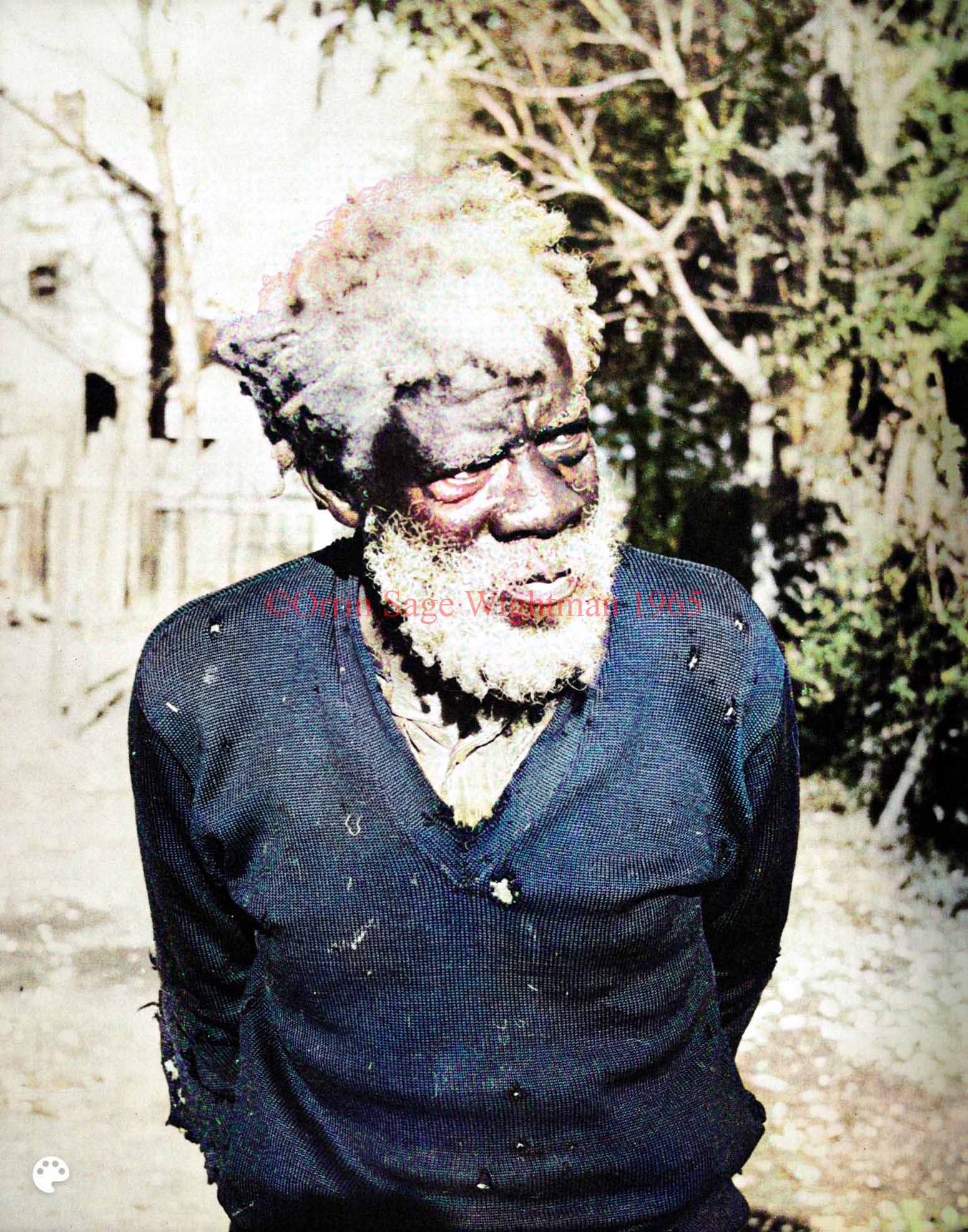

| Reverend Elijah J. Rozzell* |

167 |

| Dan Hopkins |

169 |

| Rufus McDonald |

171 |

| Ella Pinkney |

173 |

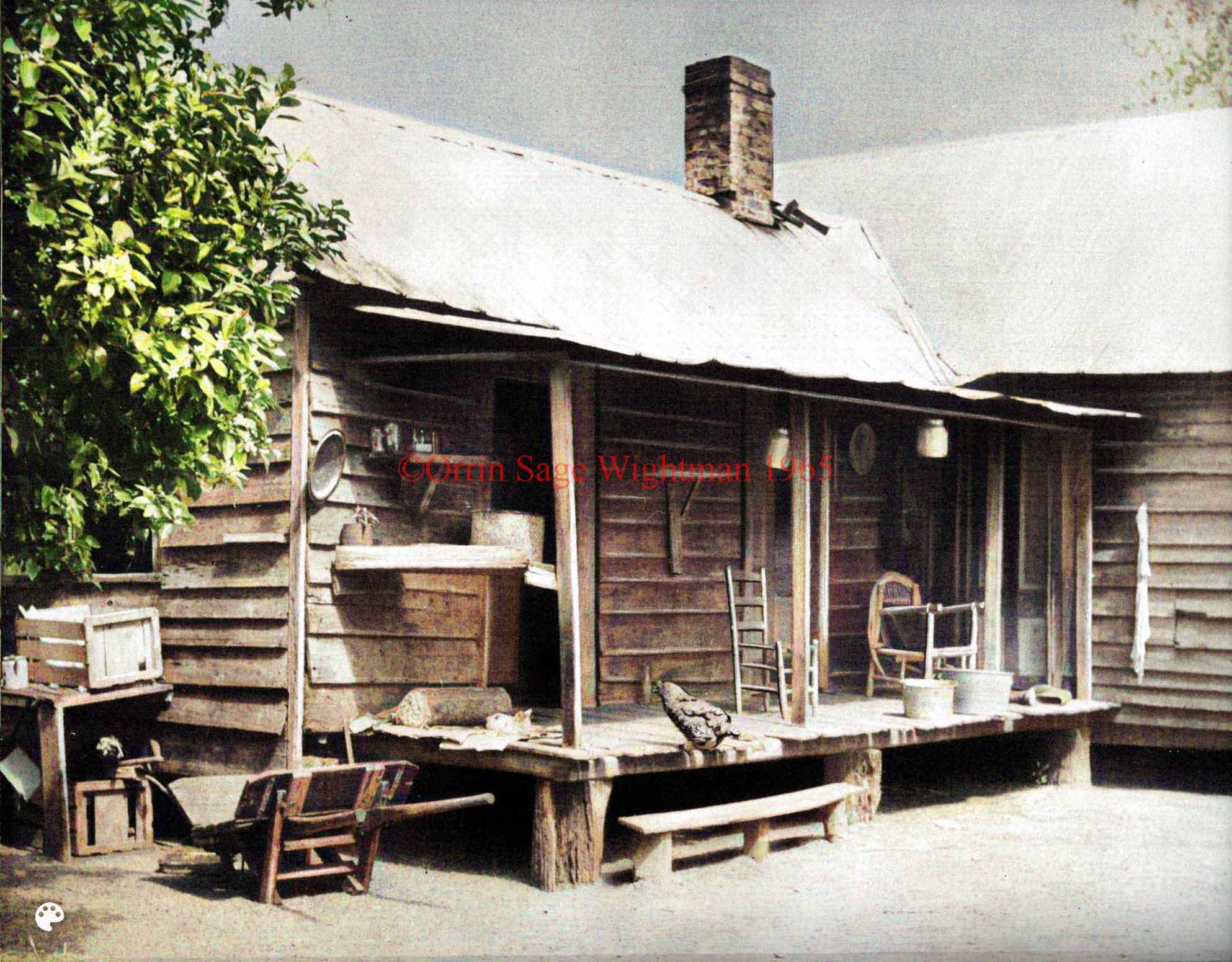

| Ella Pinkney’s Front Porch |

175 |

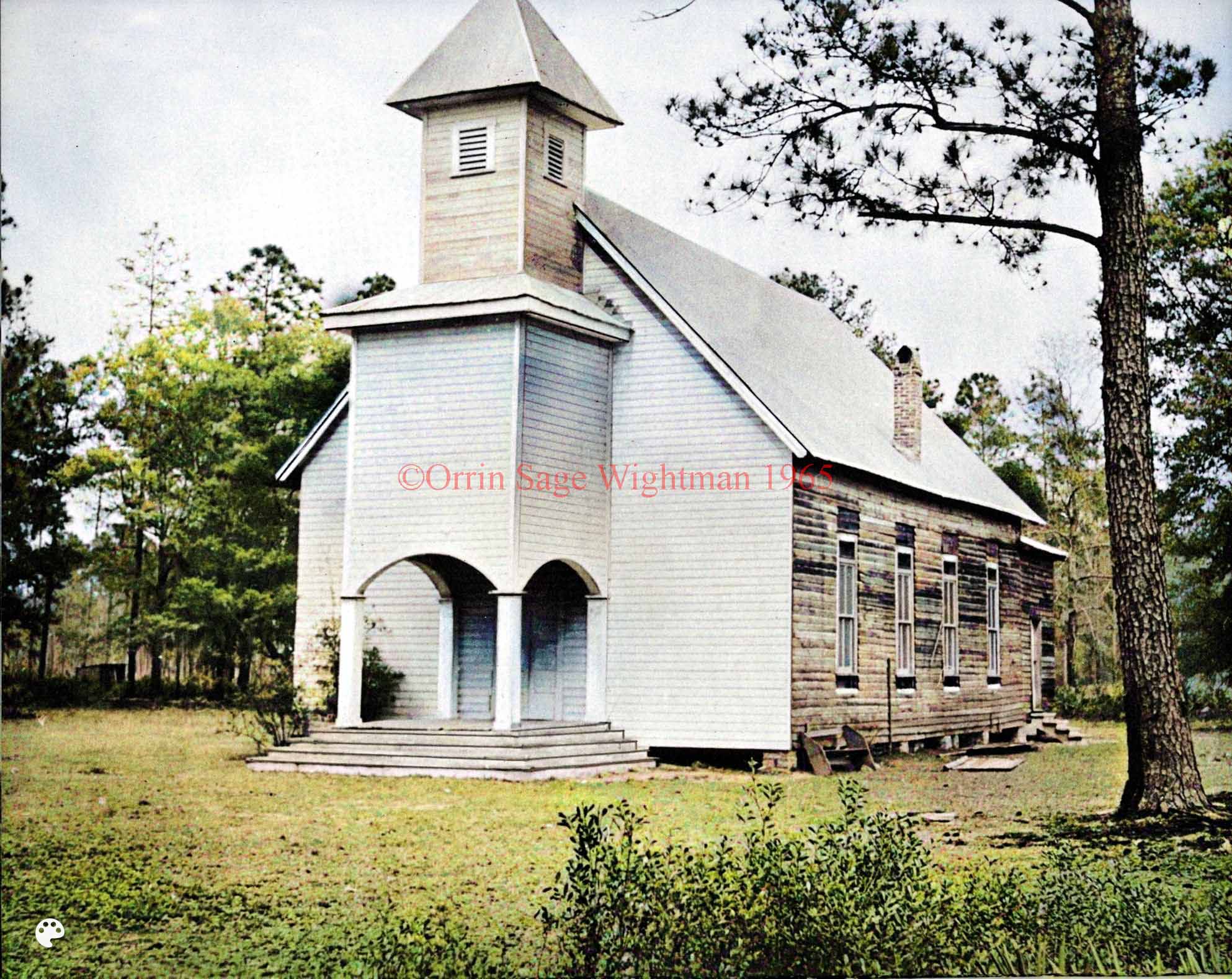

| Salem Baptist Church |

177 |

| Charles Alexander |

179 |

| Charles Alexander’s Mill |

181 |

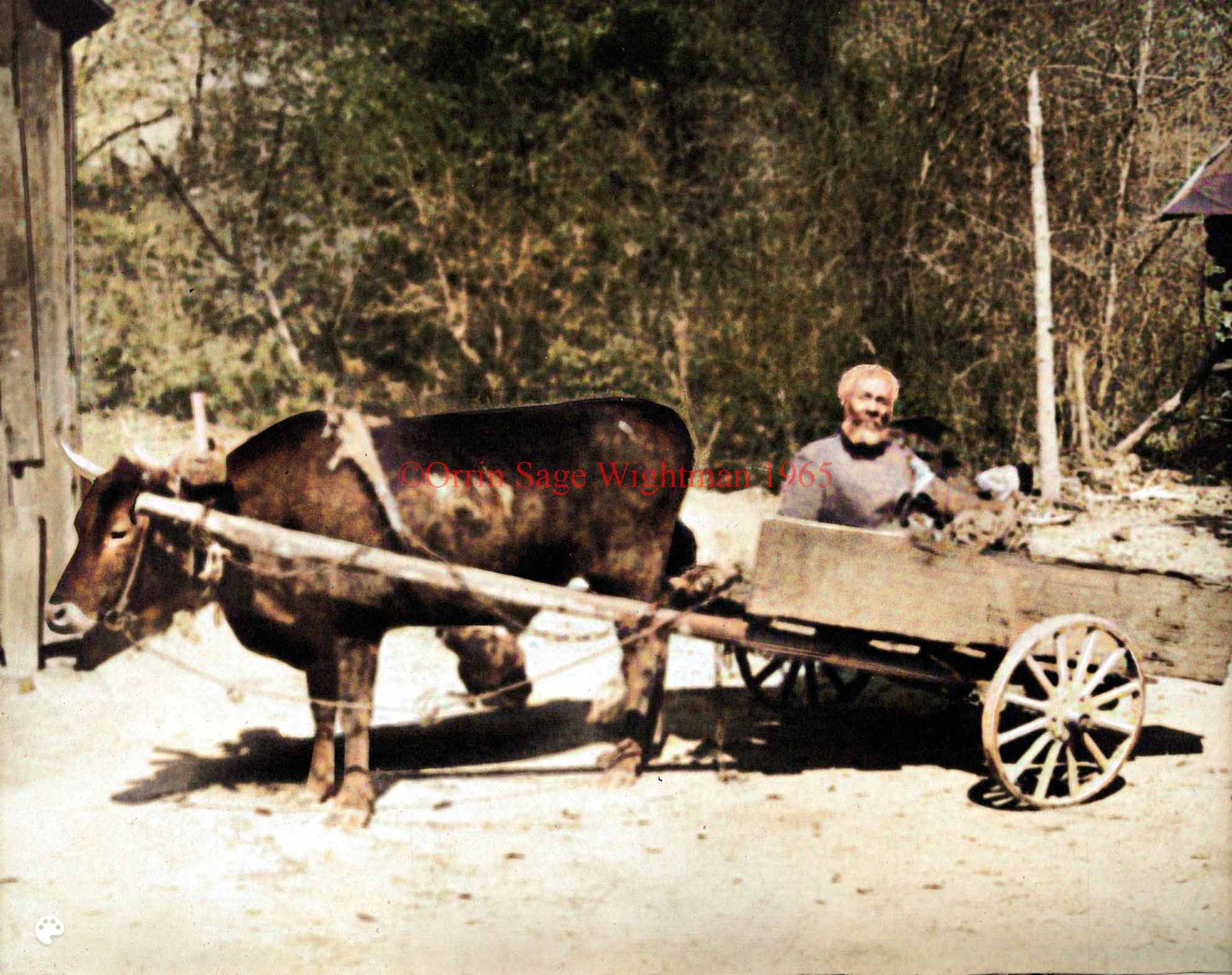

| Charles Alexander’s ox cart |

183 |

| Tyrah Wilson |

185 |

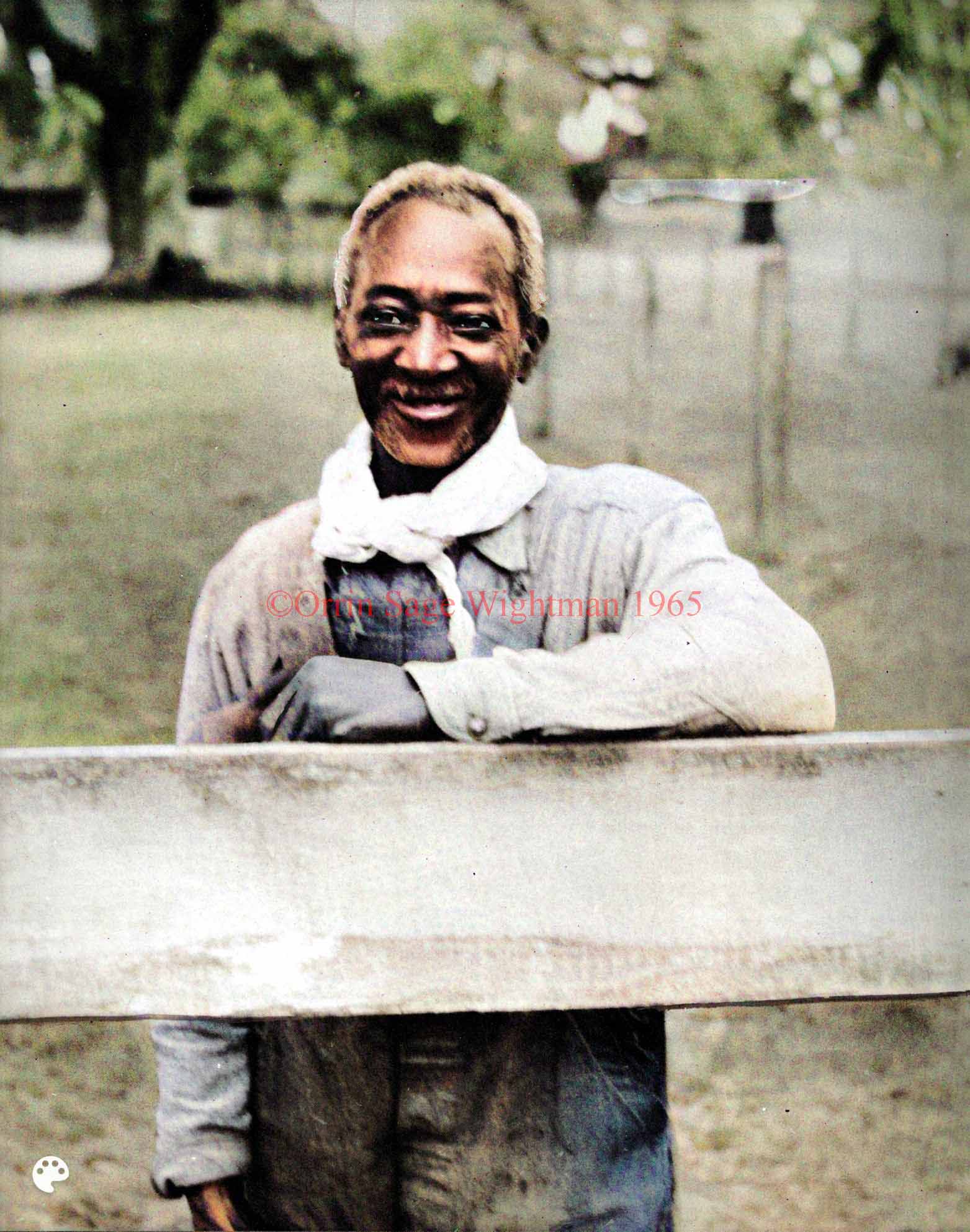

| Morris Polite |

187 |

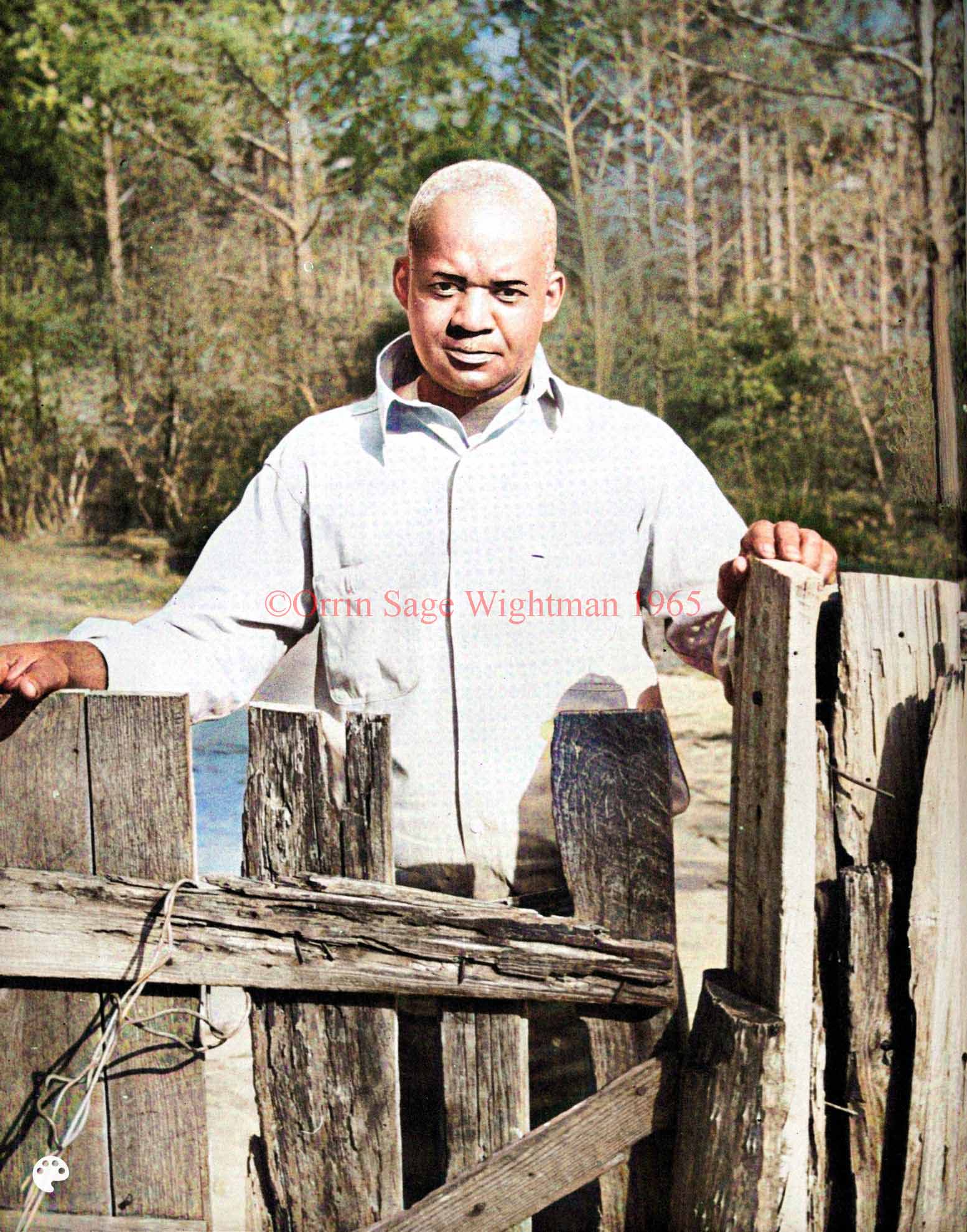

| London Polite |

189 |

| Jerry Harris |

191 |

| Jerry Harris’ back porch |

193 |

| Sibby Kelly |

195 |

| Bell Tower of Petersville Baptist

Church |

197 |

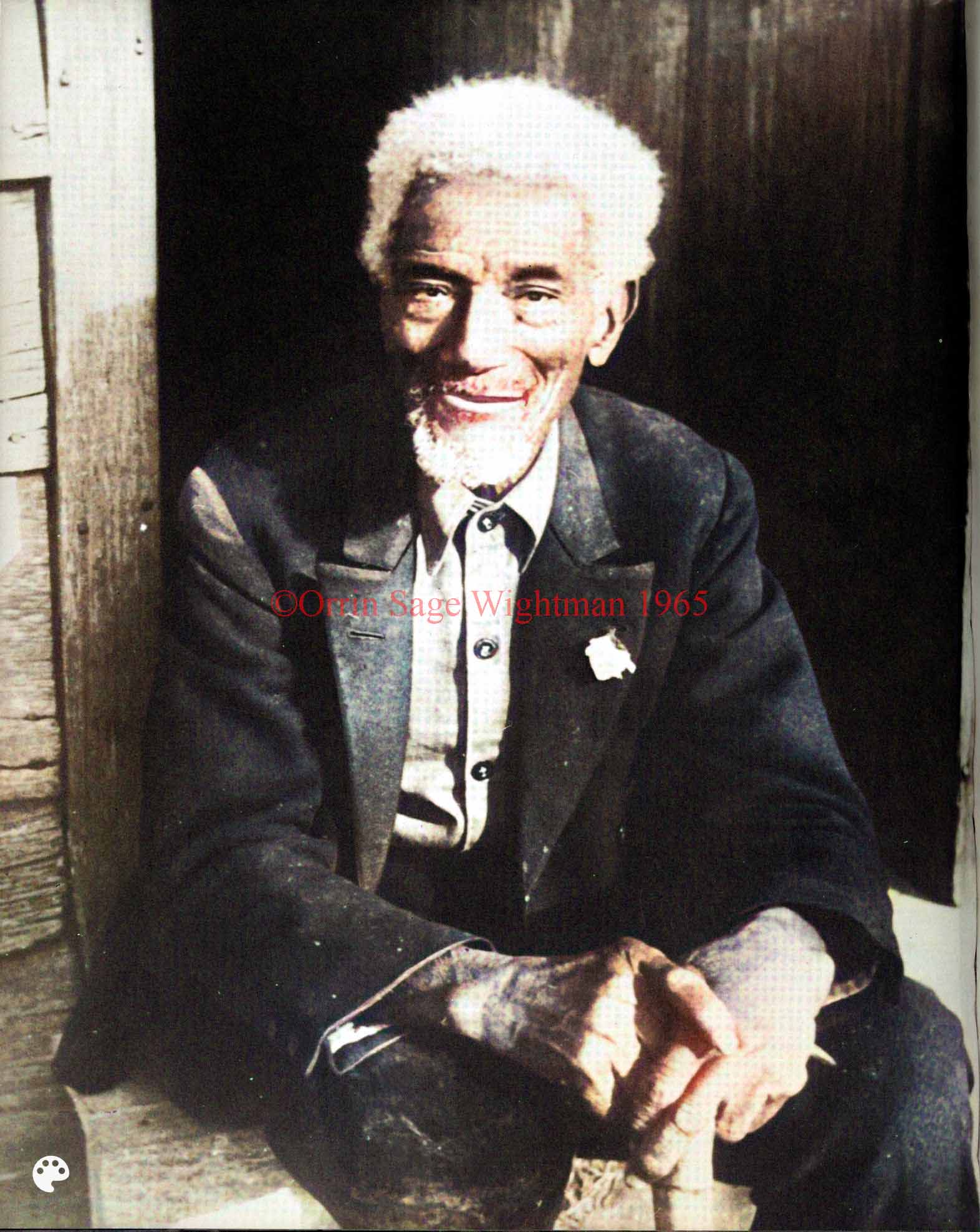

| Liverpool Hazzard |

199 |

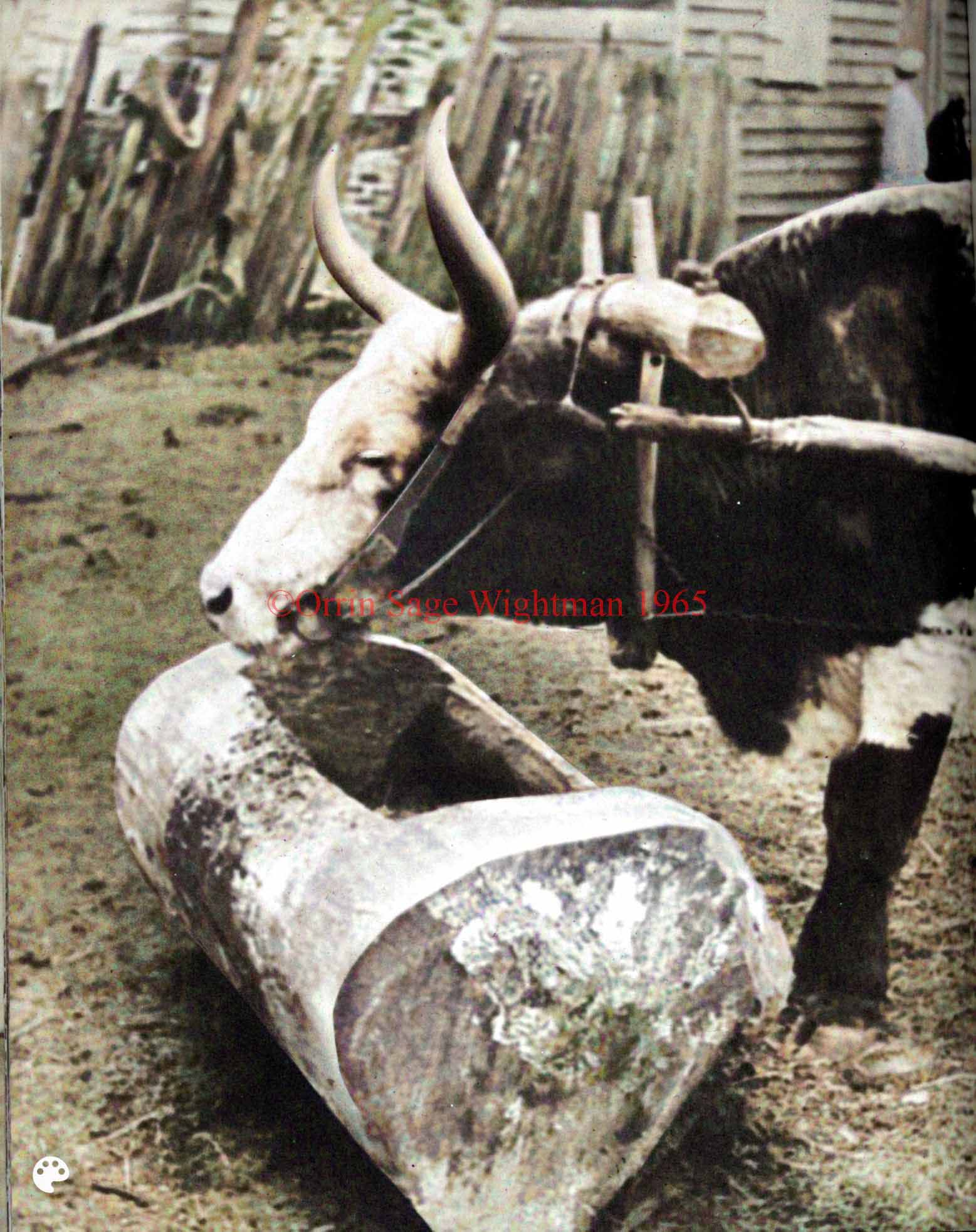

| Liverpool’s ox cart |

201 |

| Liverpool’s ox cart and trough |

203 |

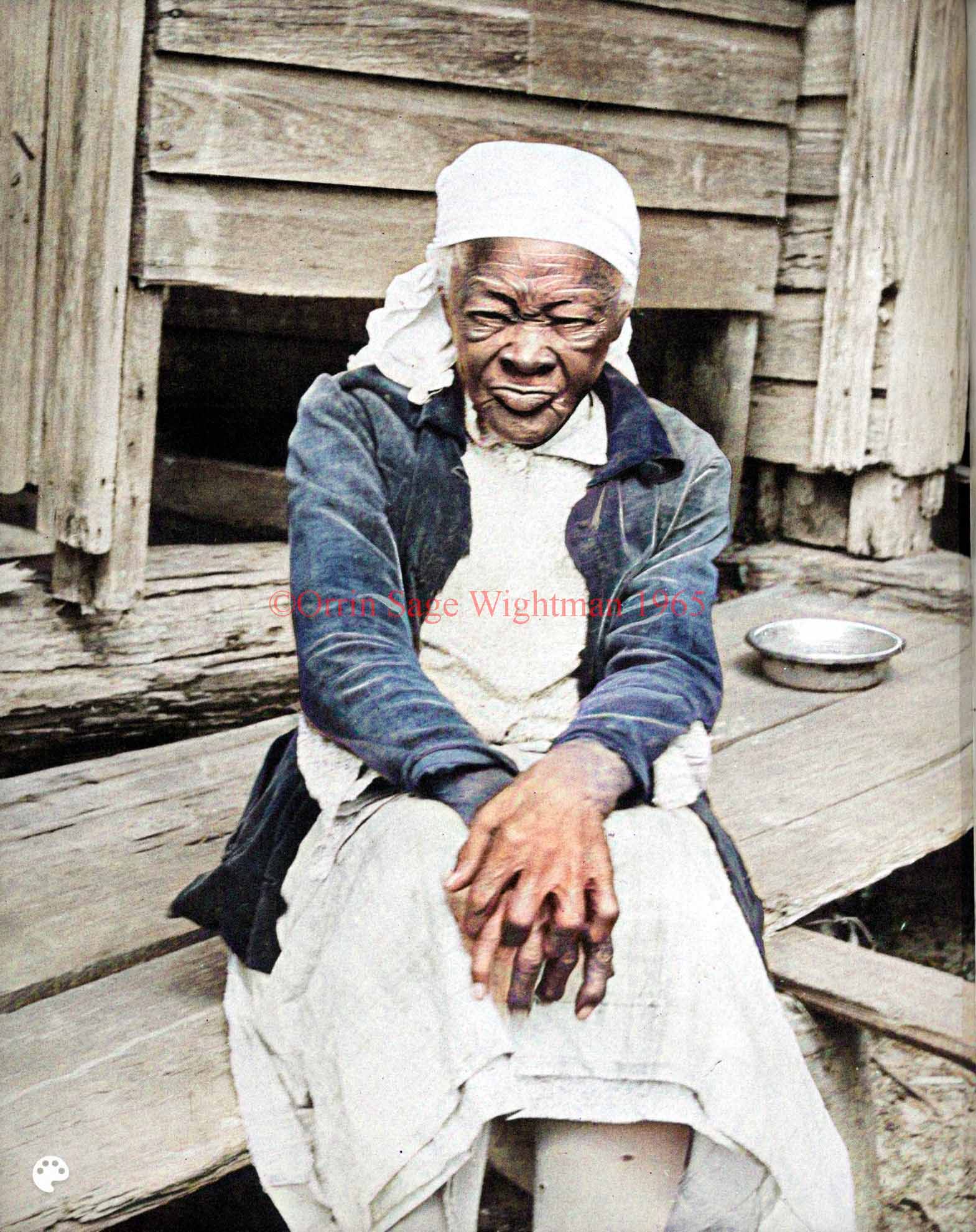

| Old Jane |

205 |

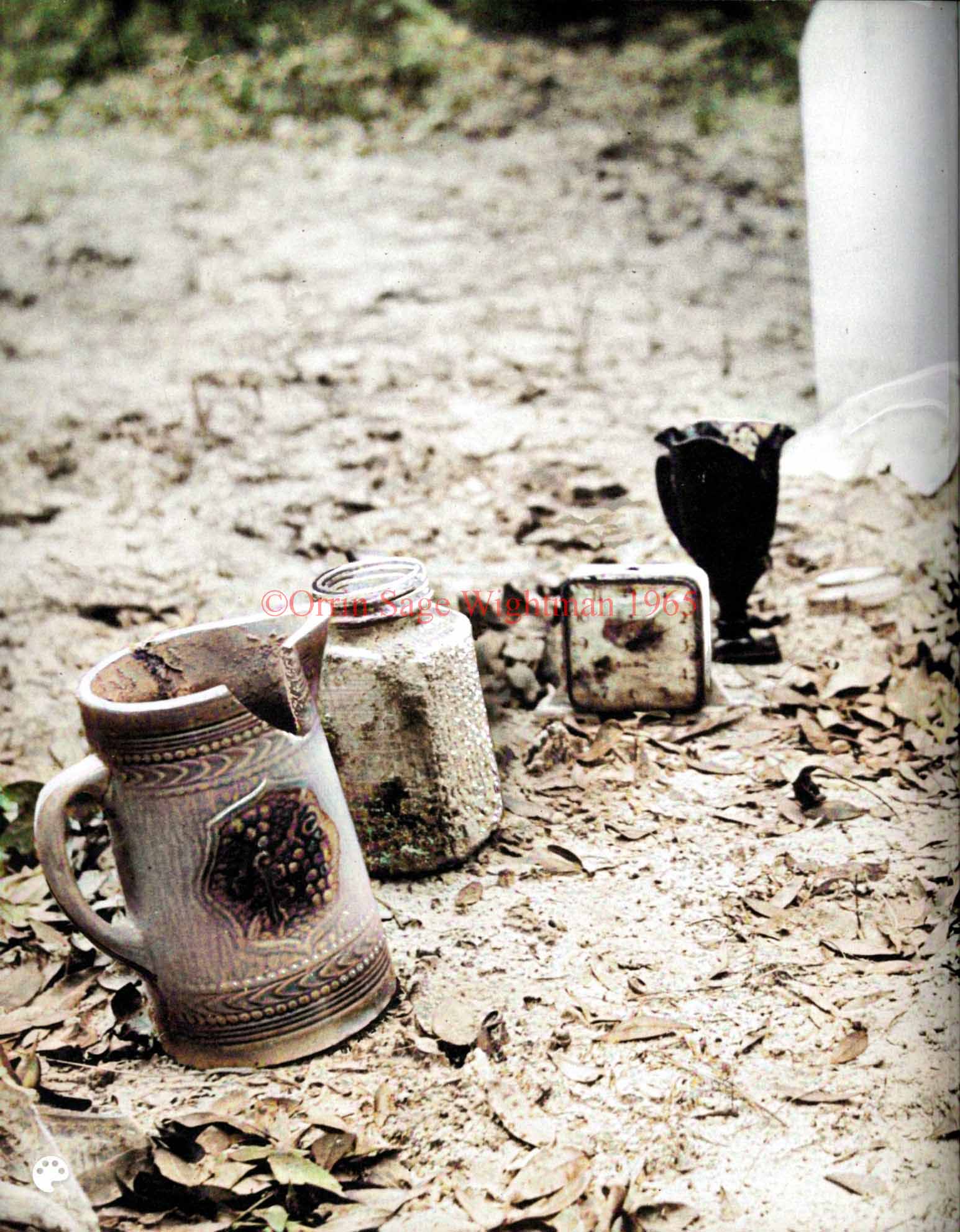

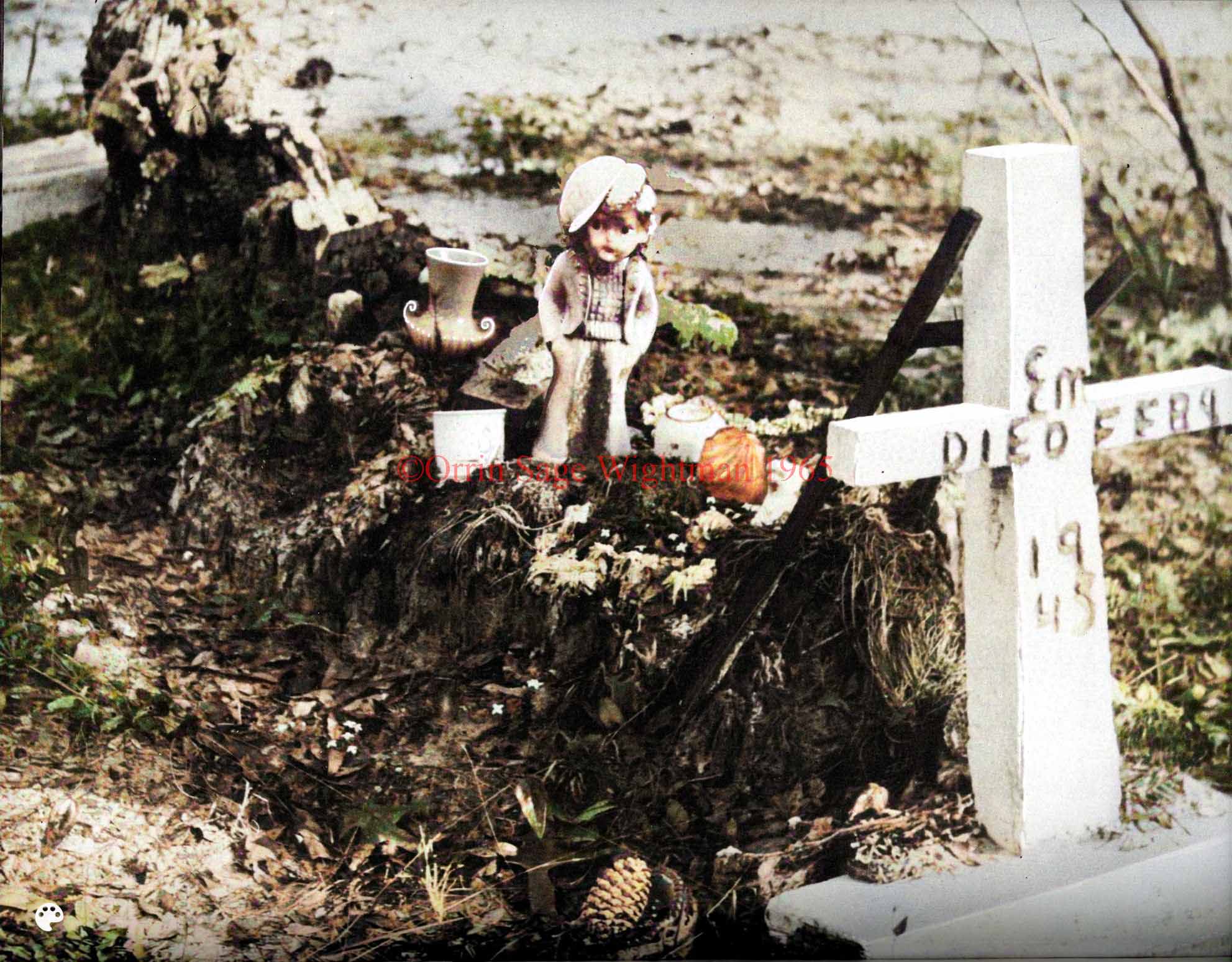

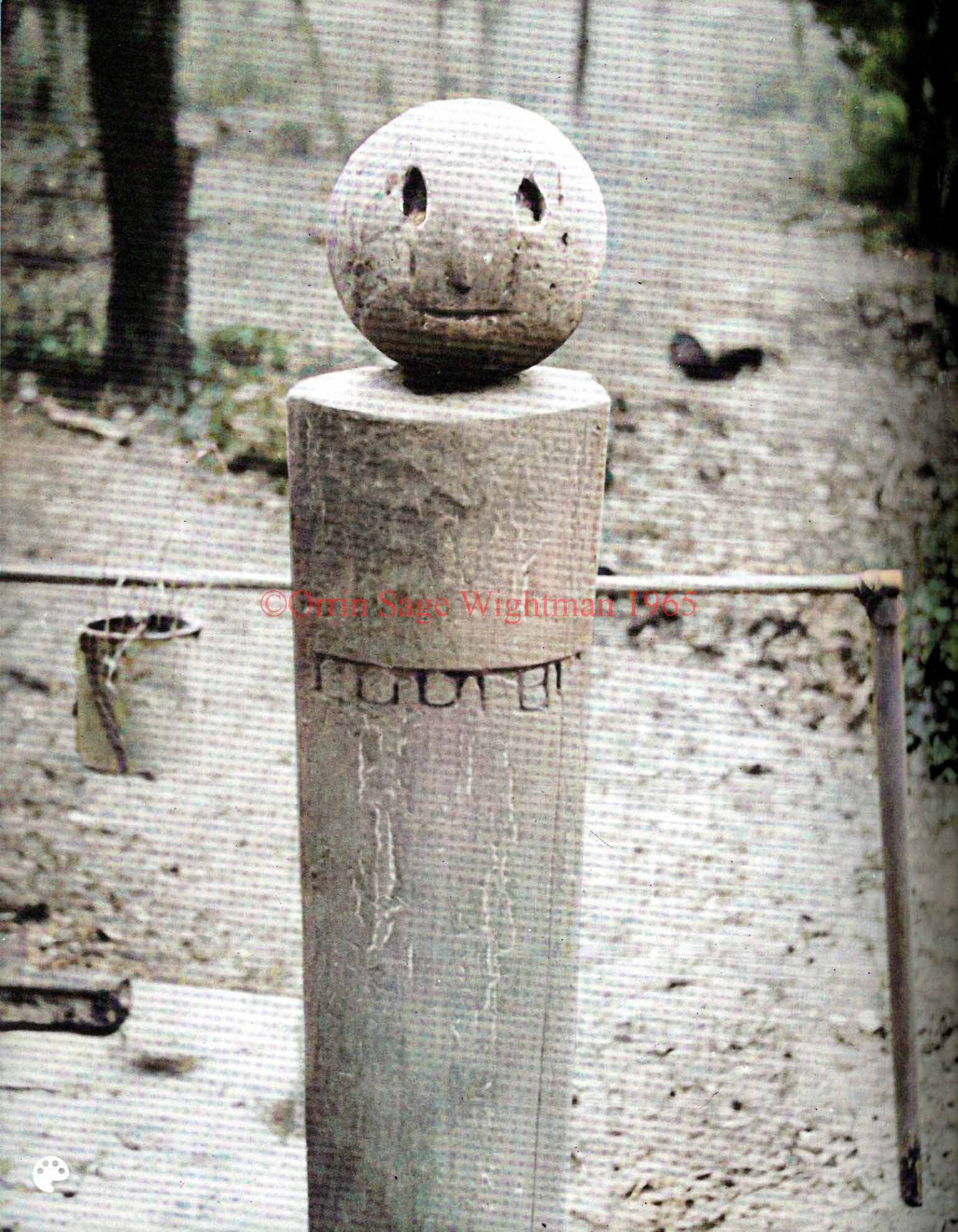

| Negro Graves |

207 |

| Jackie Coogan |

209 |

| A piggy bank |

211 |

| Superman |

213 |

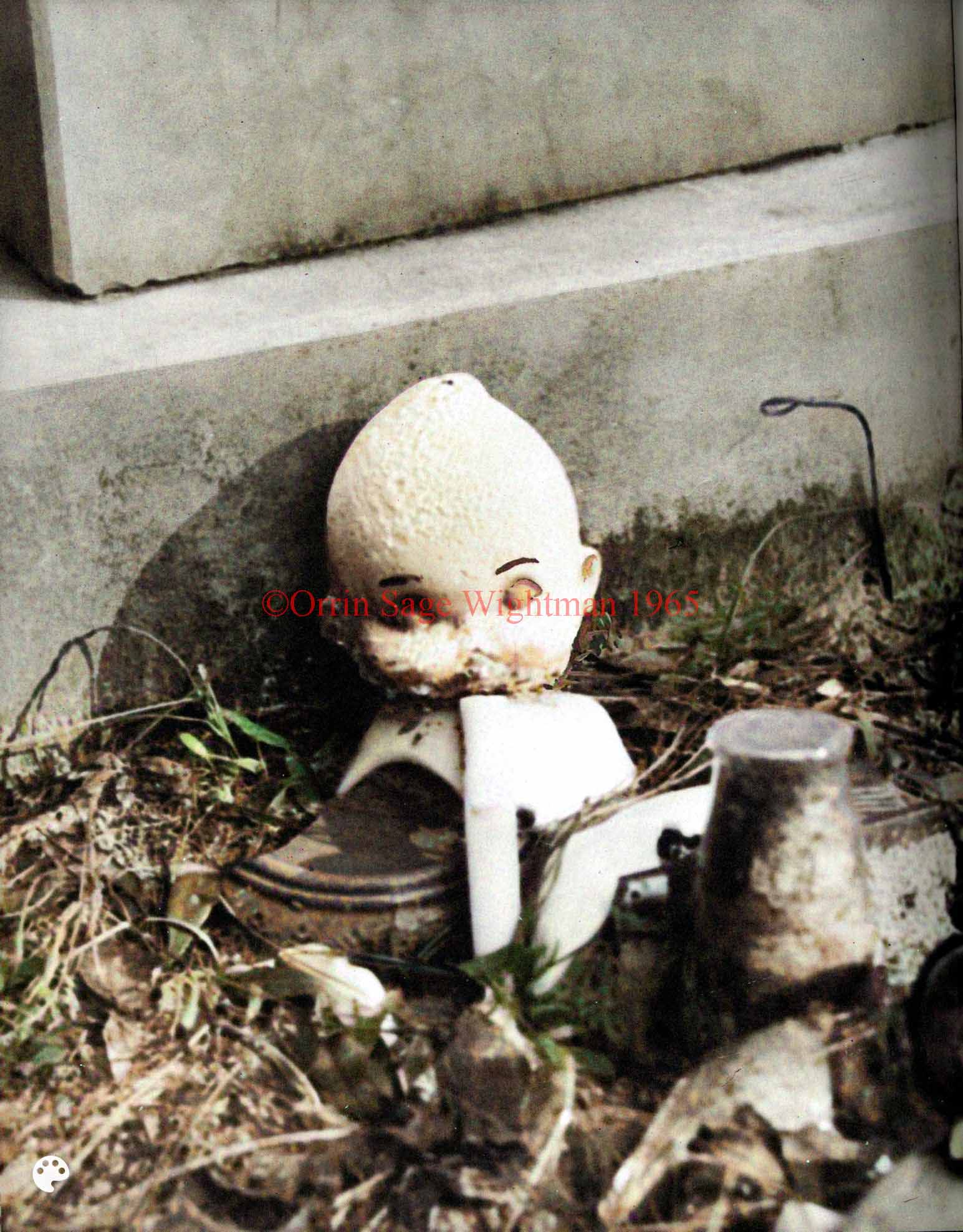

| Dolls' Head |

215 |

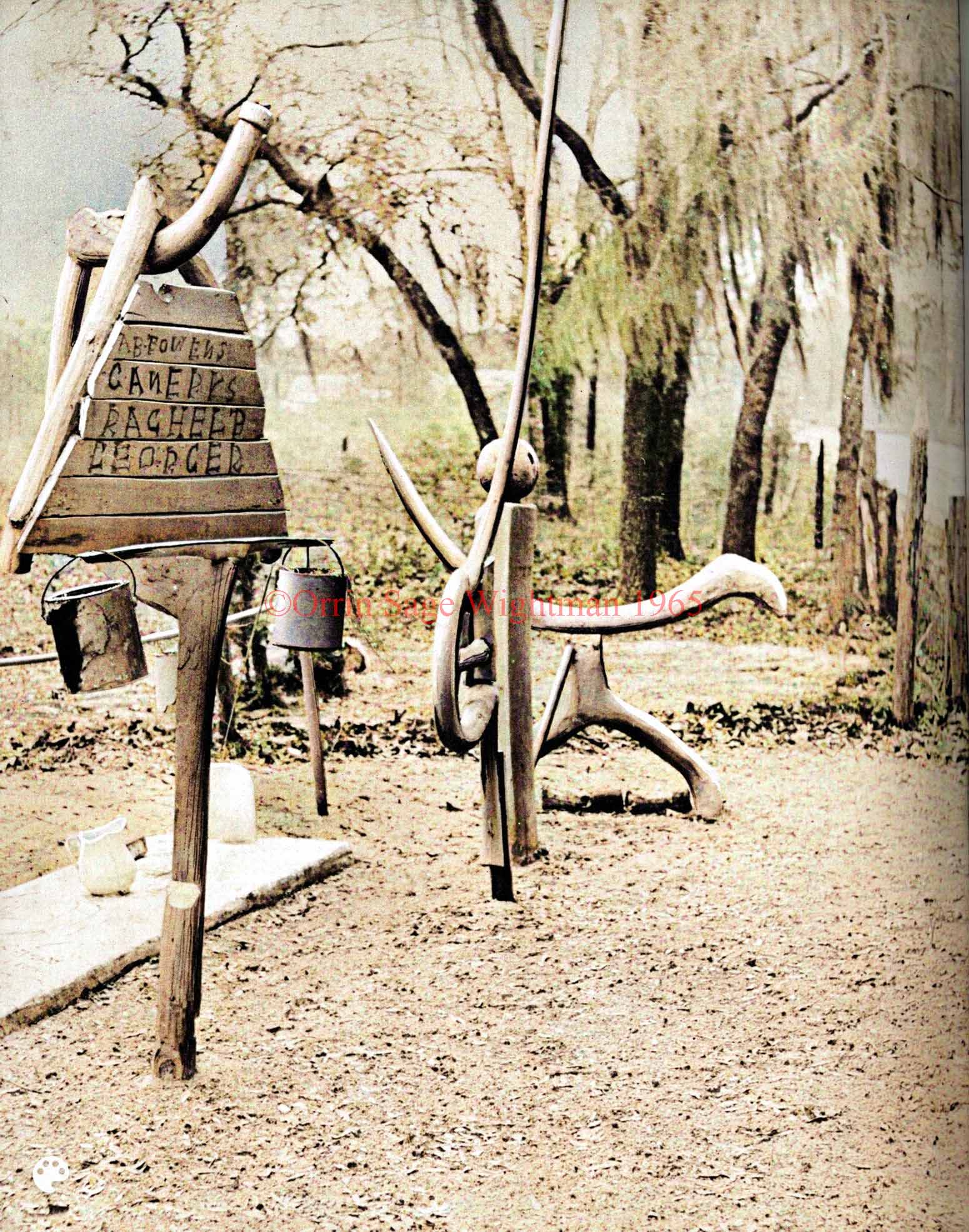

| Bowens' Family Burial Plot |

217 |

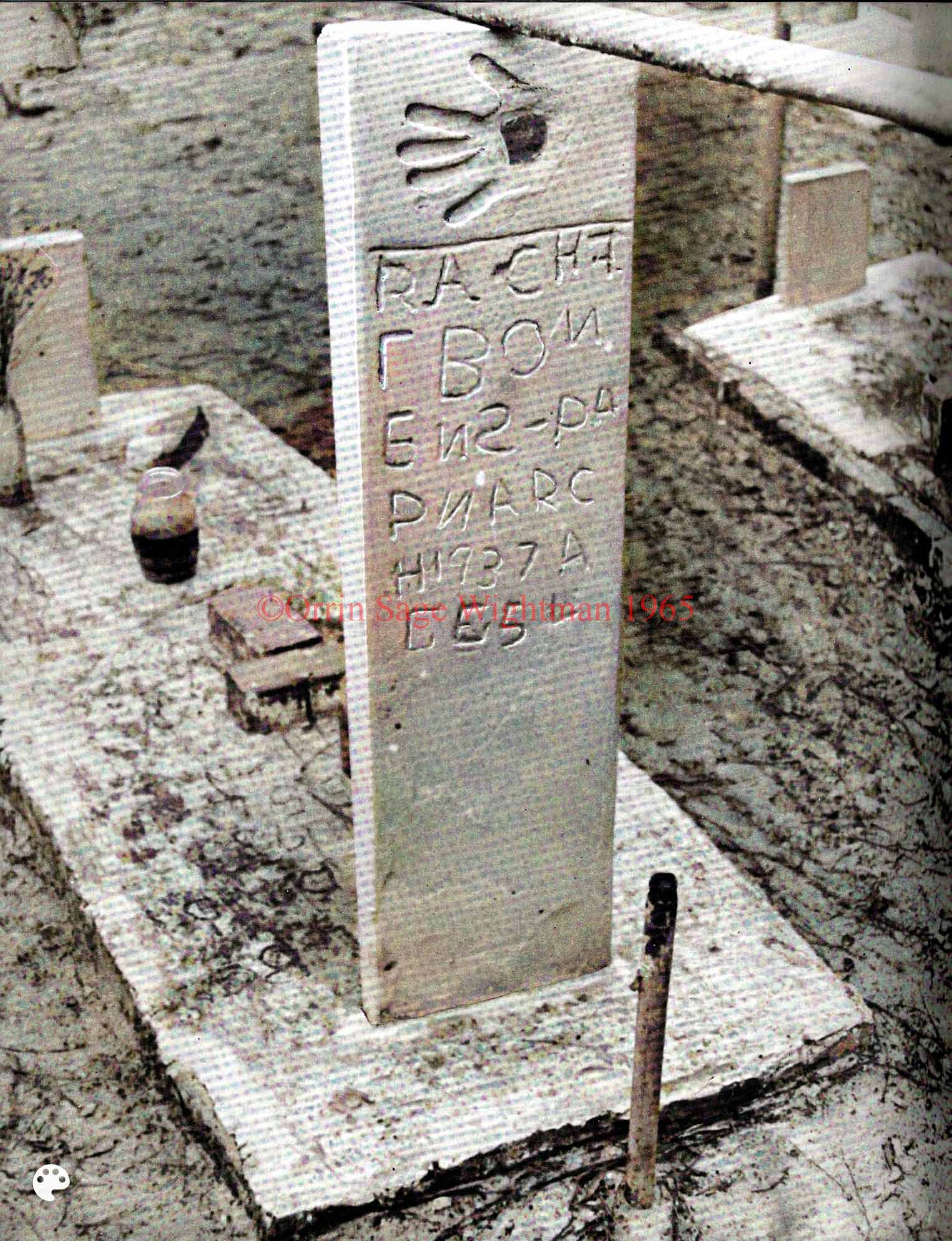

| The grave of Rachel Bowen-Pap |

221 |

| The grave of Reverend Aaron Bowens |

223 |

| The Historical background of St. Simons

Island |

224 |

*Original book made a typo in the page number

Pg. 6

Pg. 7

Contents

| Fort Frederica, St. Simons

Island, Georgia |

11 |

| Fort Frederica in the War of

Jenkins’ Earl |

13 |

| Old Frederica Cannon |

15 |

| The Barracks Building |

17 |

| The Town Moat |

19 |

| Foundations of Frederica’s Old

Houses |

21 |

| Hawkins-Davison Houses |

23 |

| Tabby |

25 |

| Fort St. Simons |

27 |

| Marker on Military Road |

29 |

| Military Road Near Bloody Marsh |

31 |

| Bloody Marsh Monument |

33 |

| Oglethorpe’s Home |

35 |

| Frederica’s Oaks |

37 |

| Frederica’s Old Burying Ground |

39 |

| Christ Church, Frederica |

41 |

| Couper Tombstones, Christ Church

Cemetery |

43 |

| Armstrong Tomb, Christ Church

Cemetery |

45 |

| Hazzard Vault, Christ Church

Cemetery |

47 |

| John Wylly’s Tombstone |

49 |

| Pink Chapel, West Point

Plantation |

51 |

| Slave Cabin, West Point

Plantation |

53 |

| Date Palm at Cannon’s Point |

55 |

| Ruins of the Kitchen, Cannon’s

Point Plantation |

57 |

| Slave Cabin, Butler Point |

59 |

| Hampton River at Butler Point |

61 |

| Mackintosh Vaults |

63 |

| Slave Cabins of Hamilton

Plantation |

65 |

| Ebo Landing |

67 |

| Ruins of Retreat Plantation

House |

69 |

| Retreat Avenue |

71 |

| Retreat Avenue and Baldwin’s

Ditch |

73 |

| Retreat Hospital |

75 |

| Sea Island Golf Club House |

77 |

| Slave Cabin of Retreat

Plantation |

79 |

|

Pg. 8

Contents

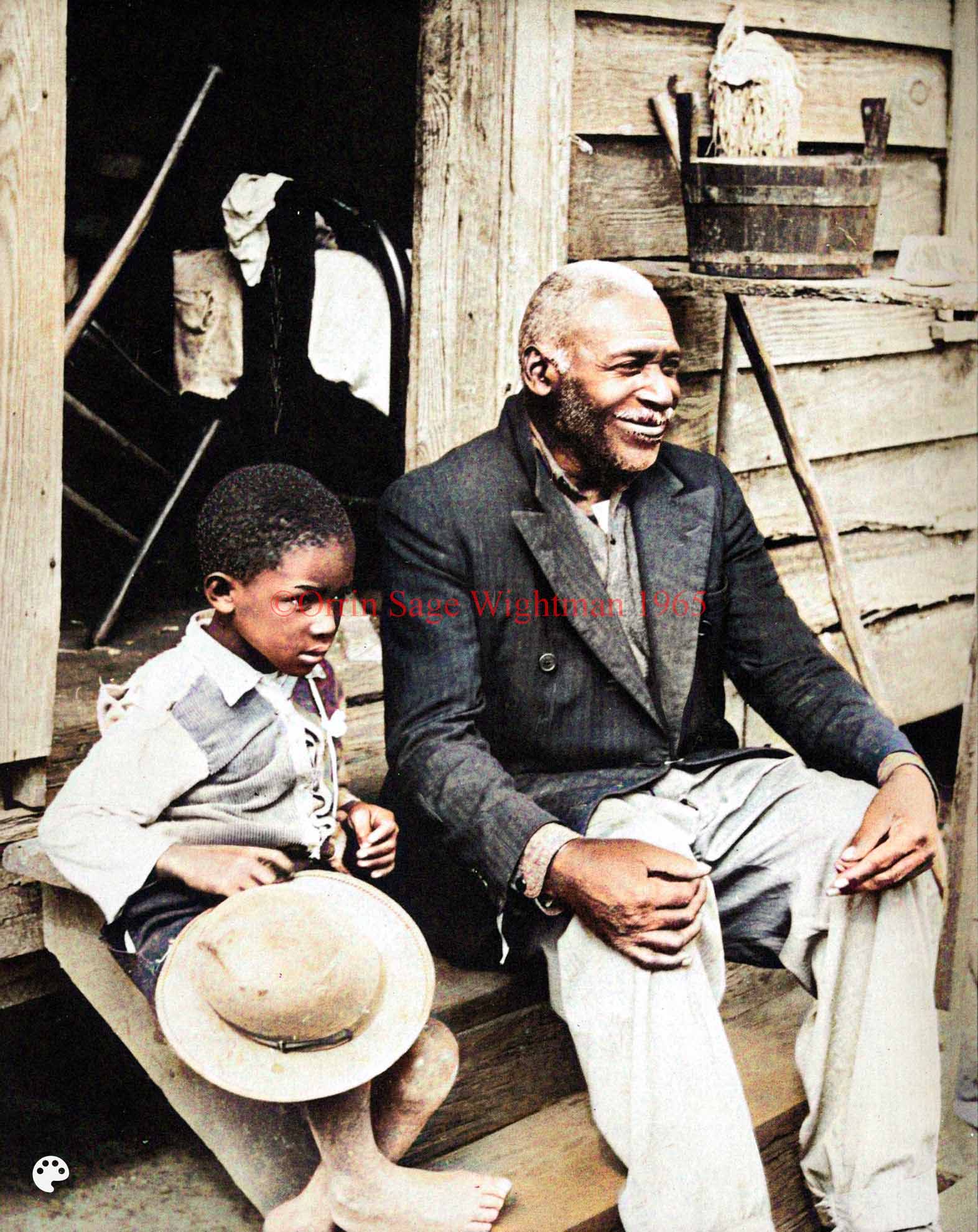

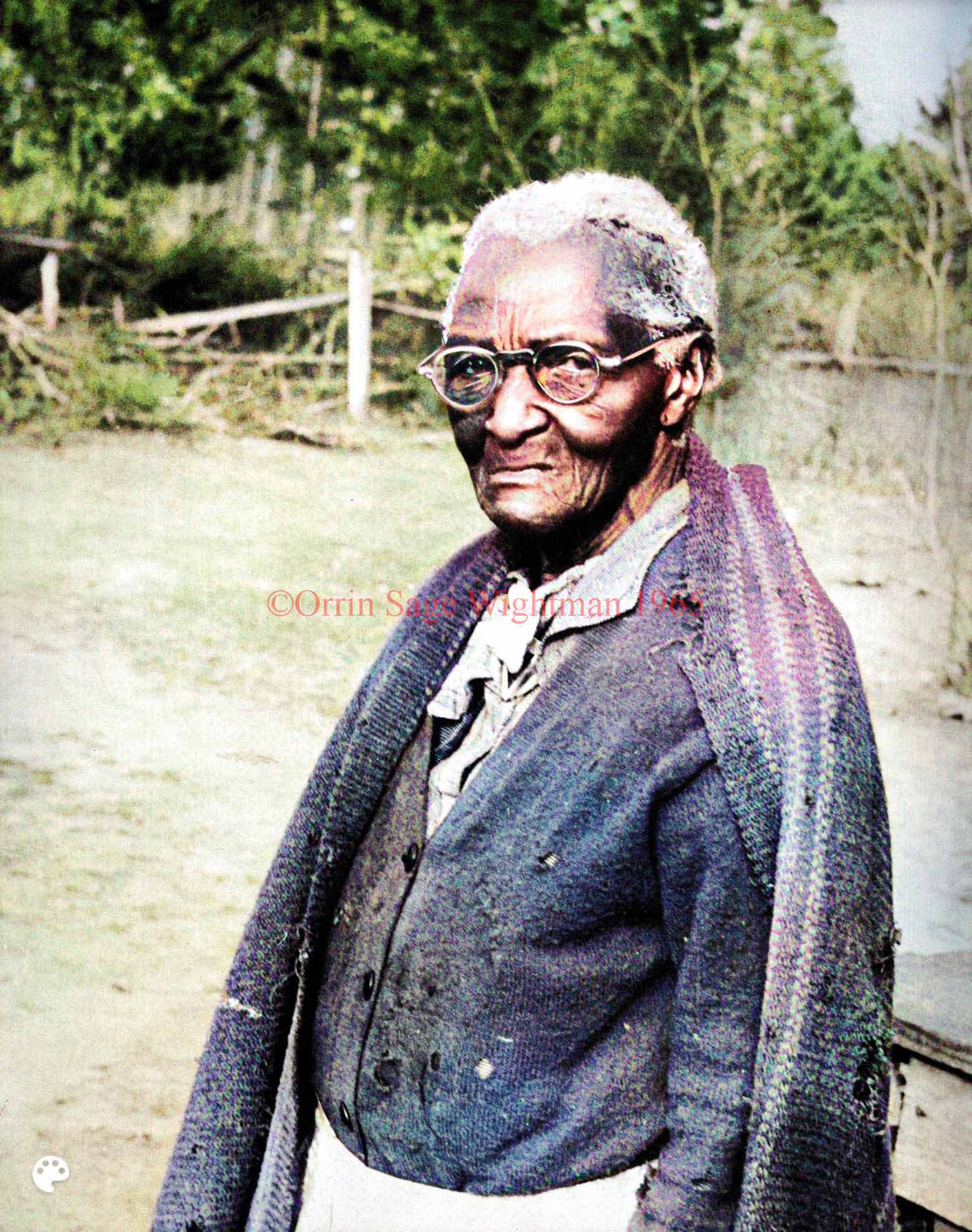

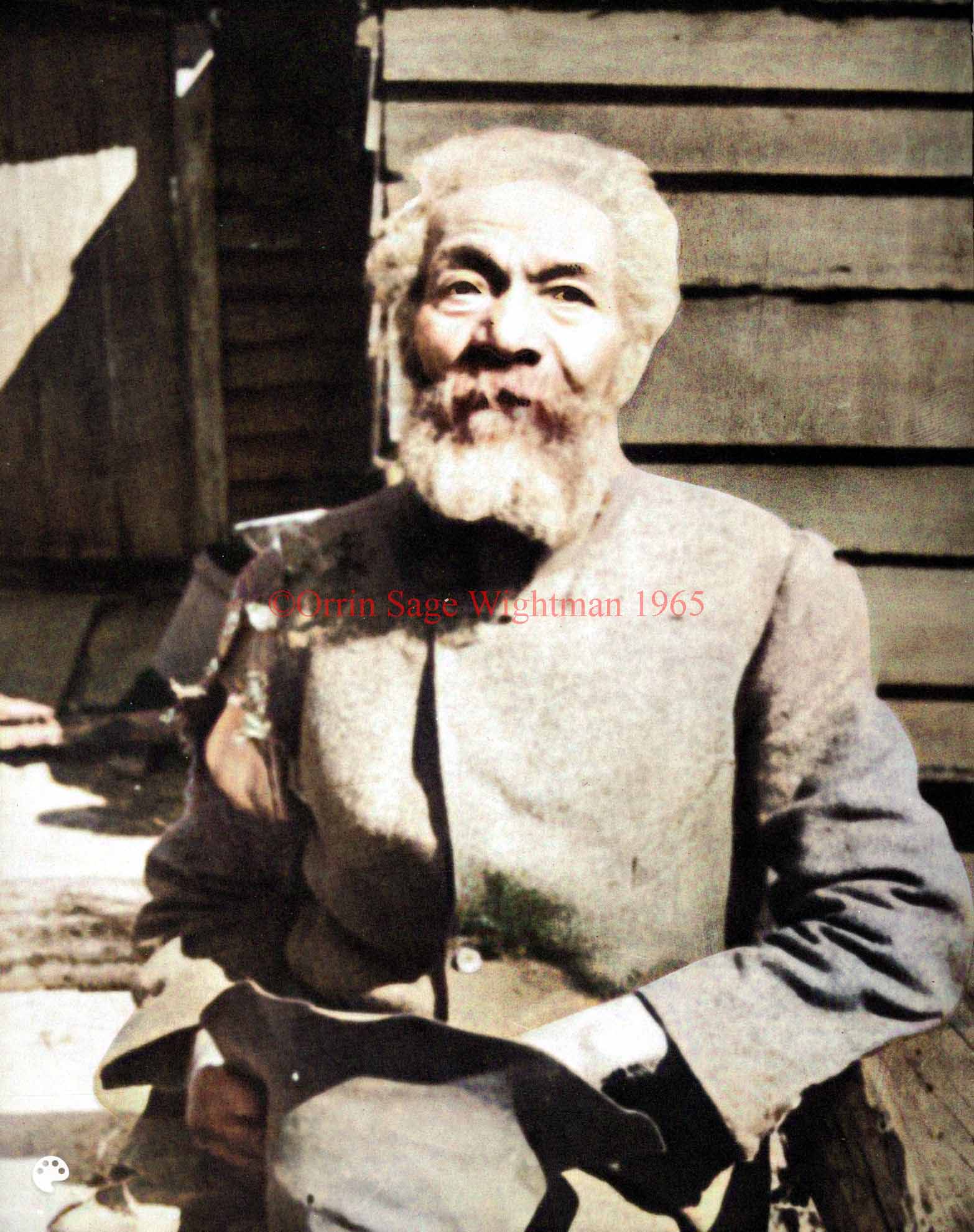

| Floyd White |

81 |

| Frizzle Chicken |

83 |

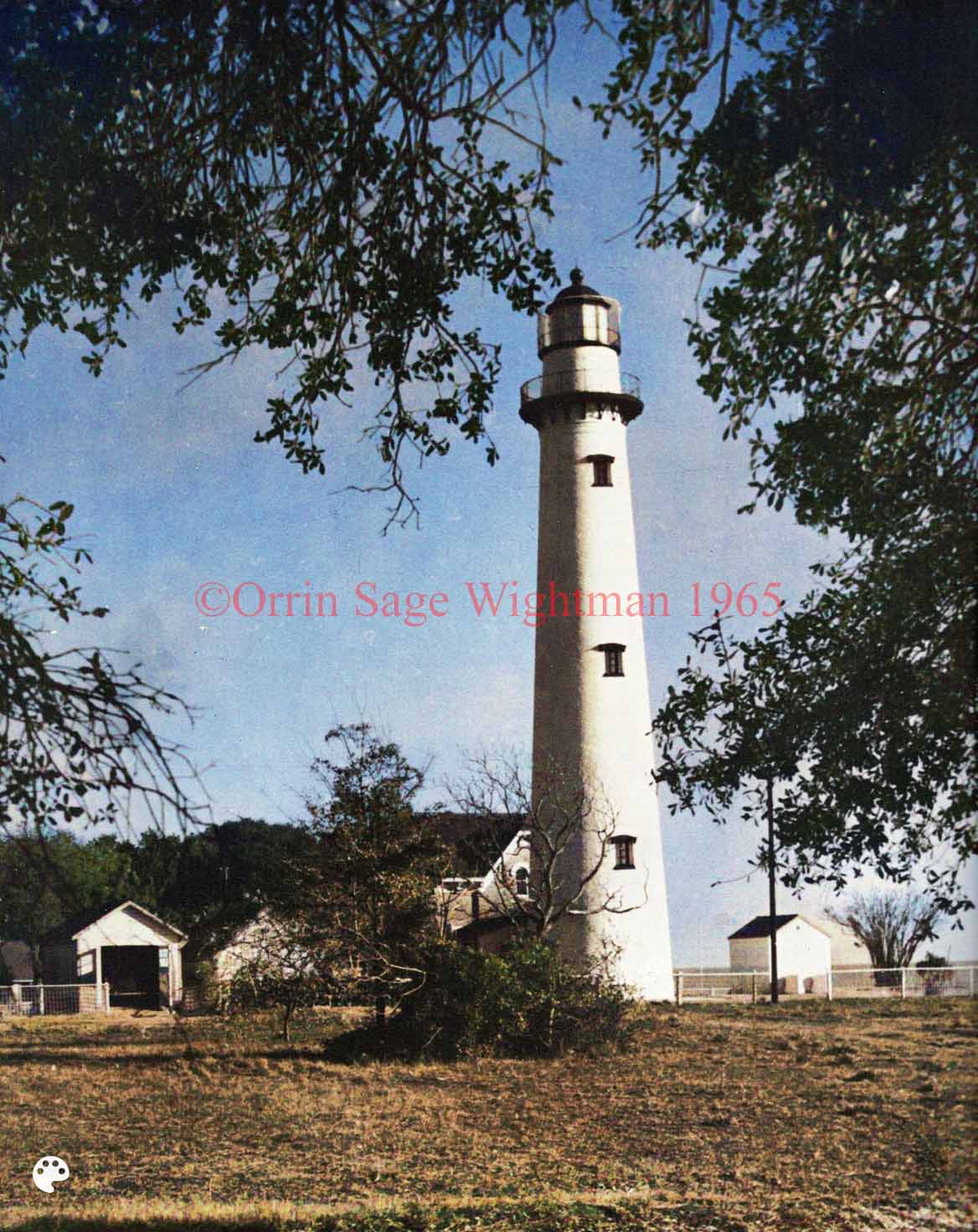

| St. Simons Lighthouse |

85 |

| Lanier’s Oak |

87 |

| The Marshes of Glynn |

89 |

| Lanier’s Marshes |

91 |

| Lovers’ Oak |

93 |

| Capt. Mark Carr, Brunswick’s

First Settler |

95 |

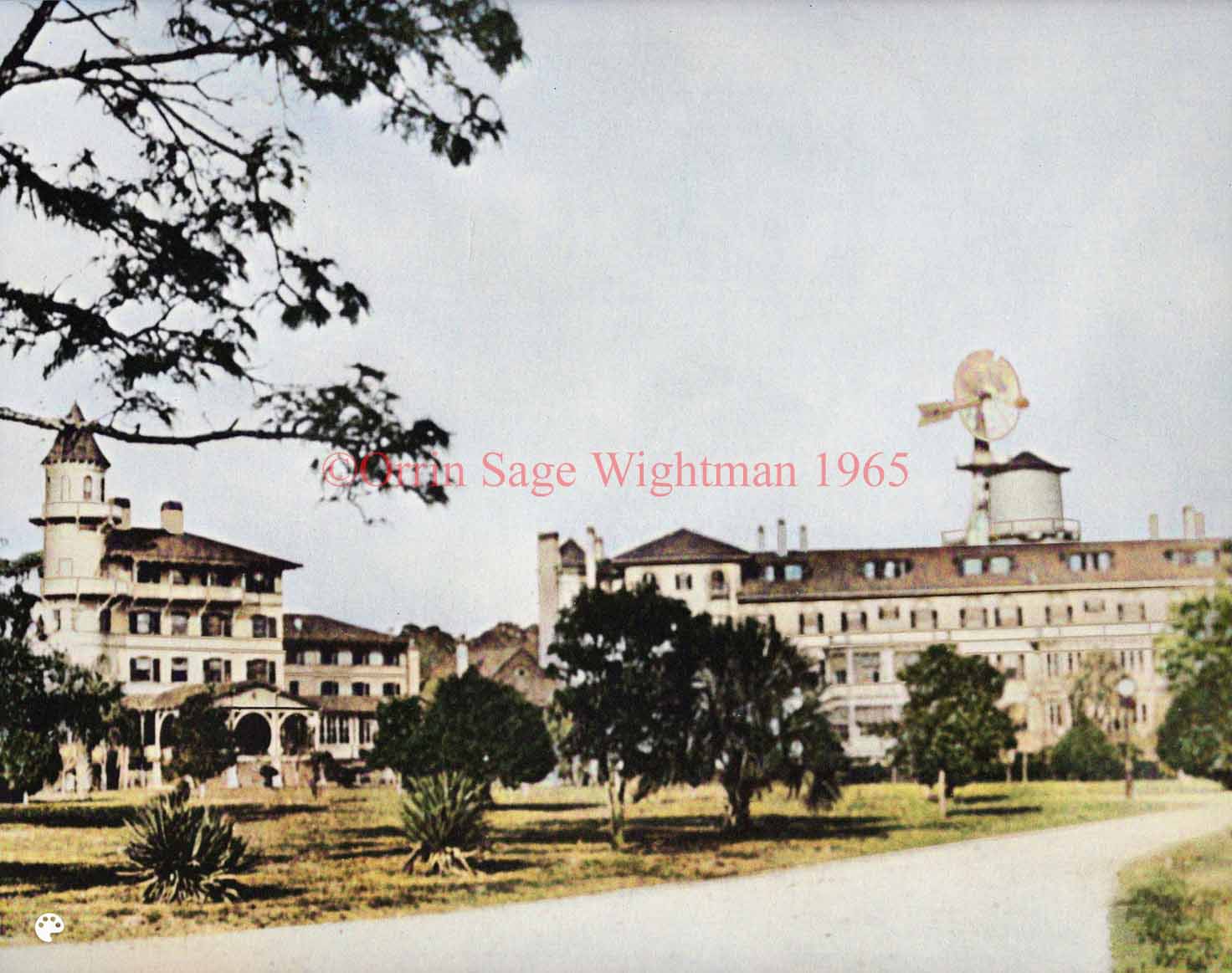

| Oglethorpe Hotel, Brunswick |

97 |

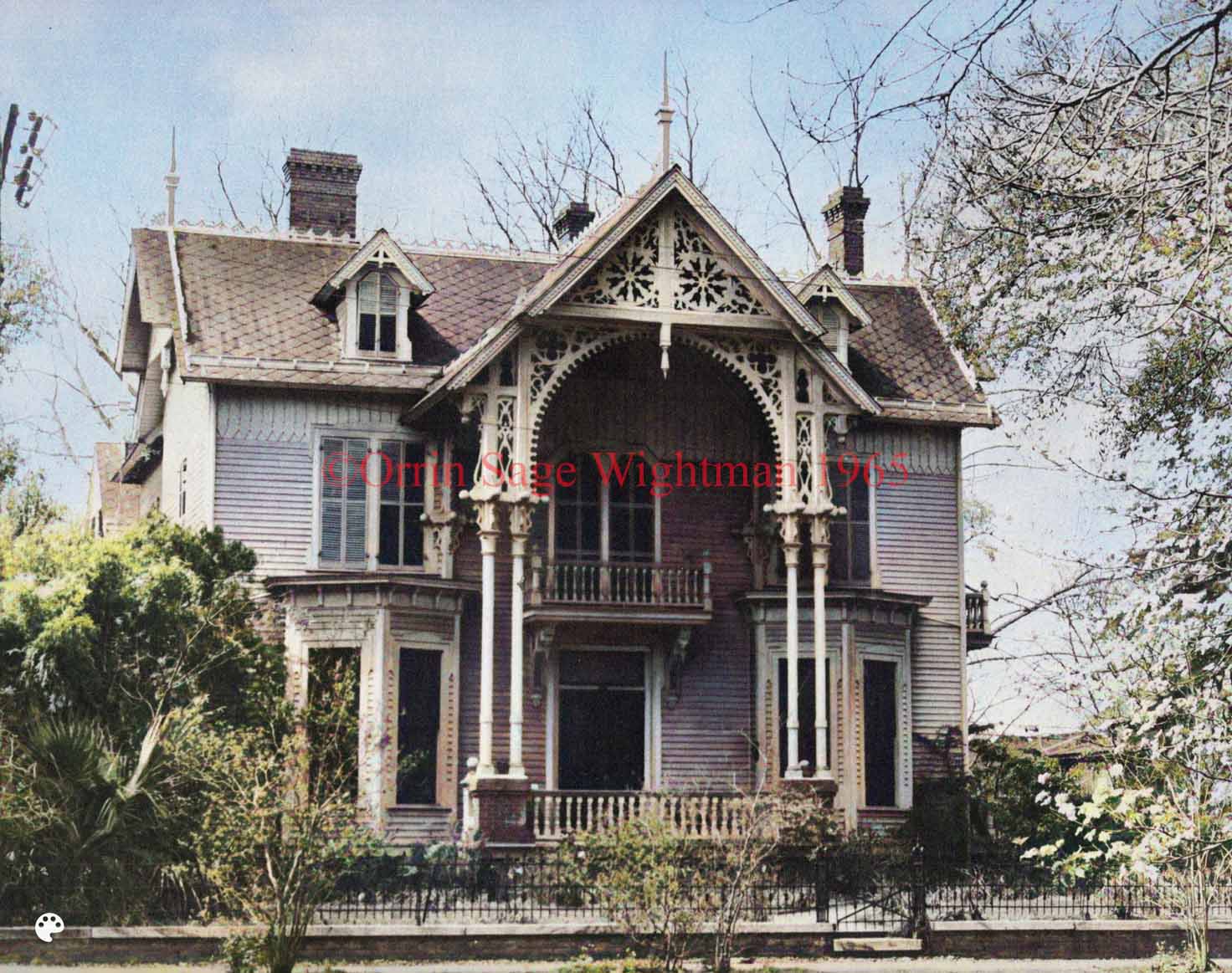

| Mahoney House |

99 |

| Jekyll Island Club |

101 |

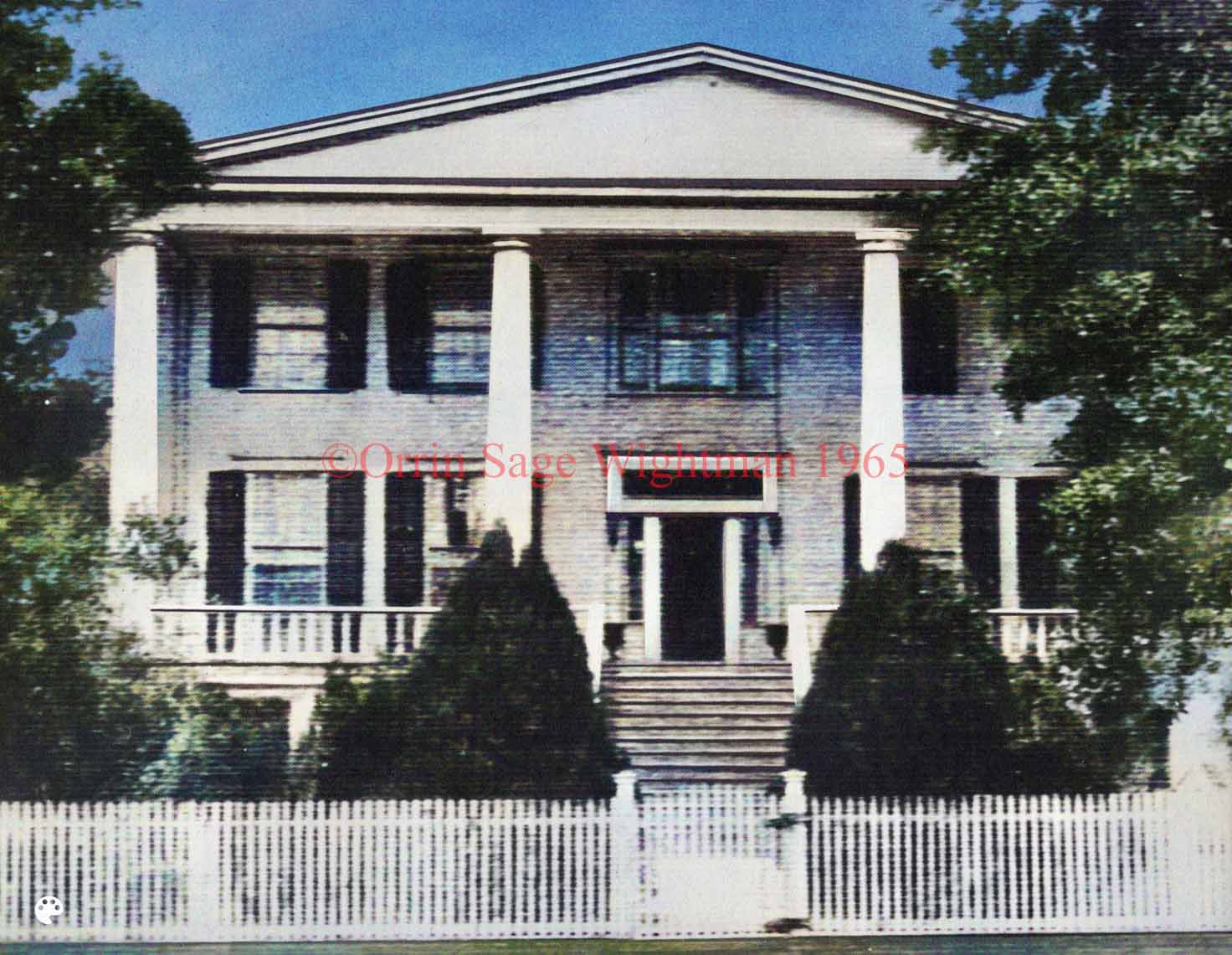

| Orange Hall, St. Marys, Georgia |

103 |

| Residence of Major Archibald

Clark, St. Marys, Georgia |

105 |

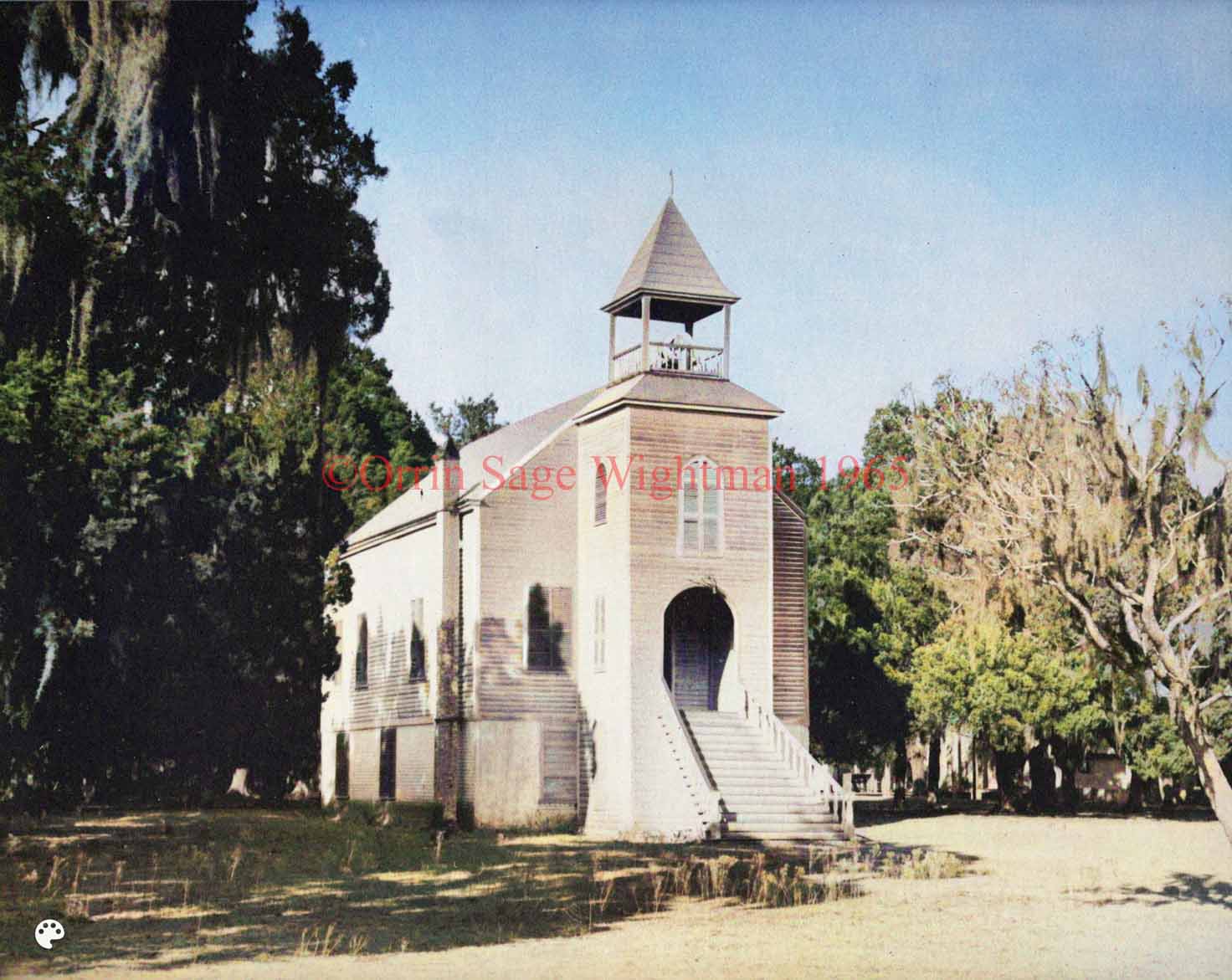

| St. Marys Presbyterian Church |

107 |

| Oak Grove Cemetery, St. Marys,

Georgia |

109 |

| The French at St. Marys |

111 |

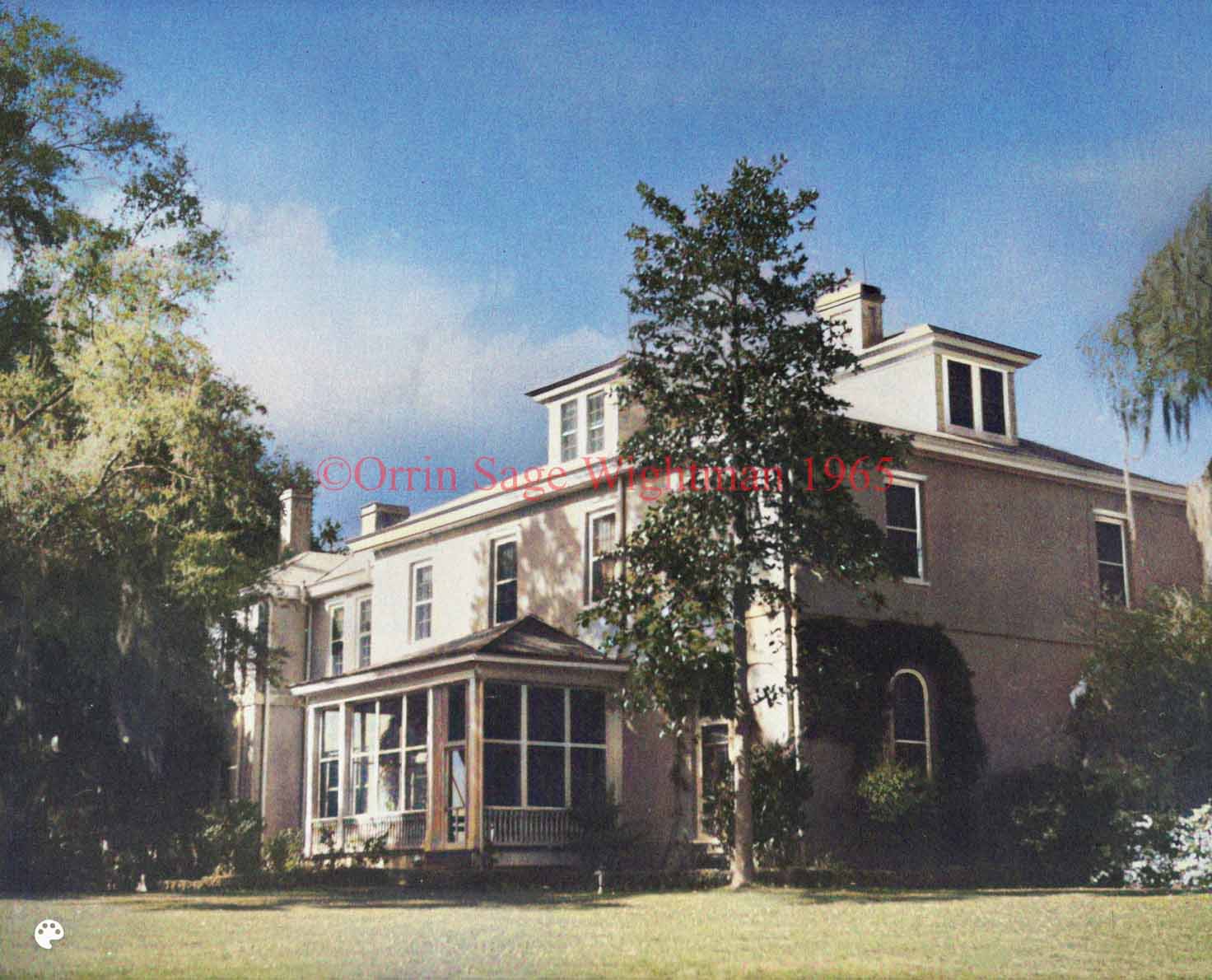

| Hofwyl Plantation |

113 |

| Altama |

115 |

| Old Rice Mill on Butler Island |

117 |

| Rice Mill Chimney on Butler

Island |

119 |

| Rice Field Canal |

121 |

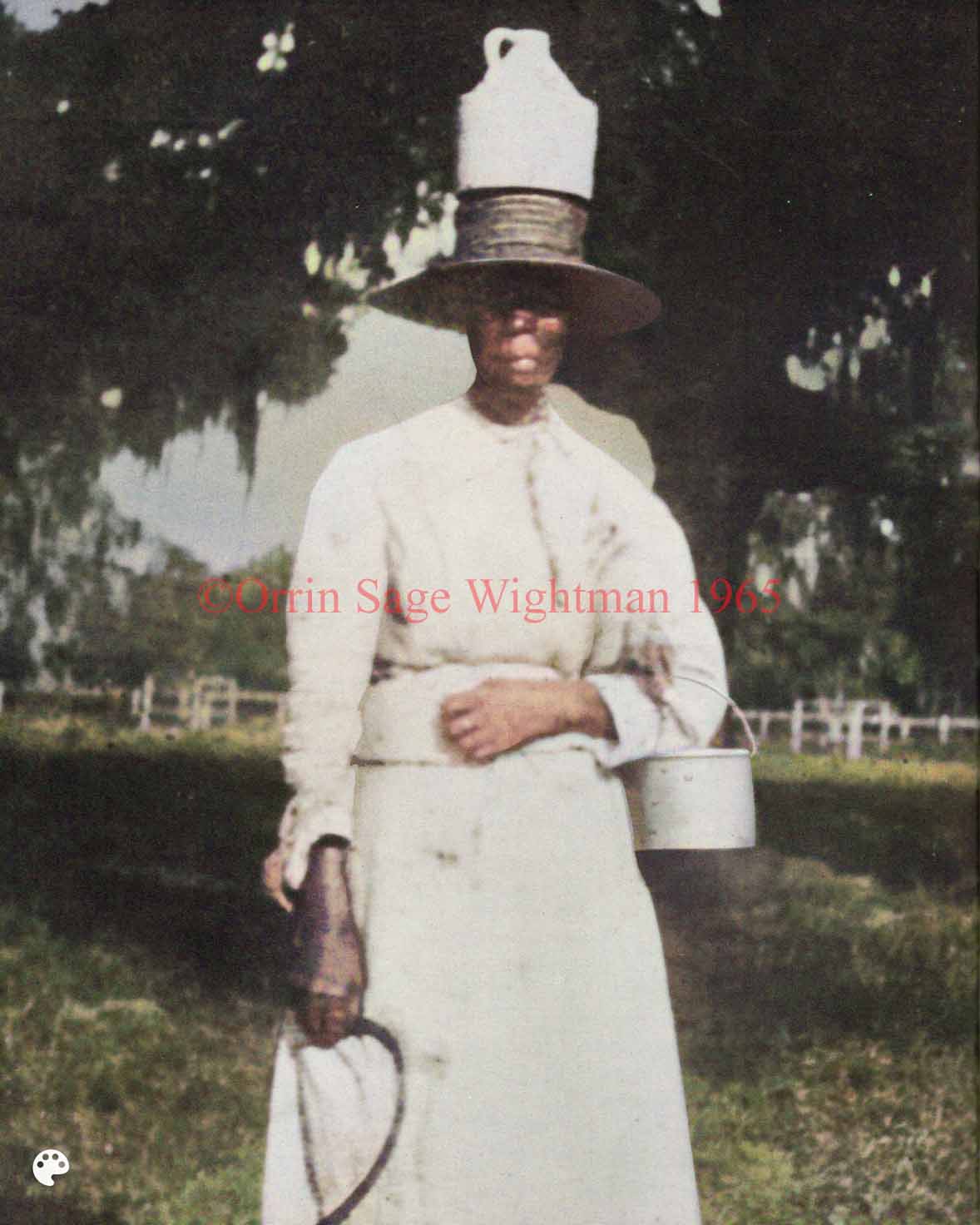

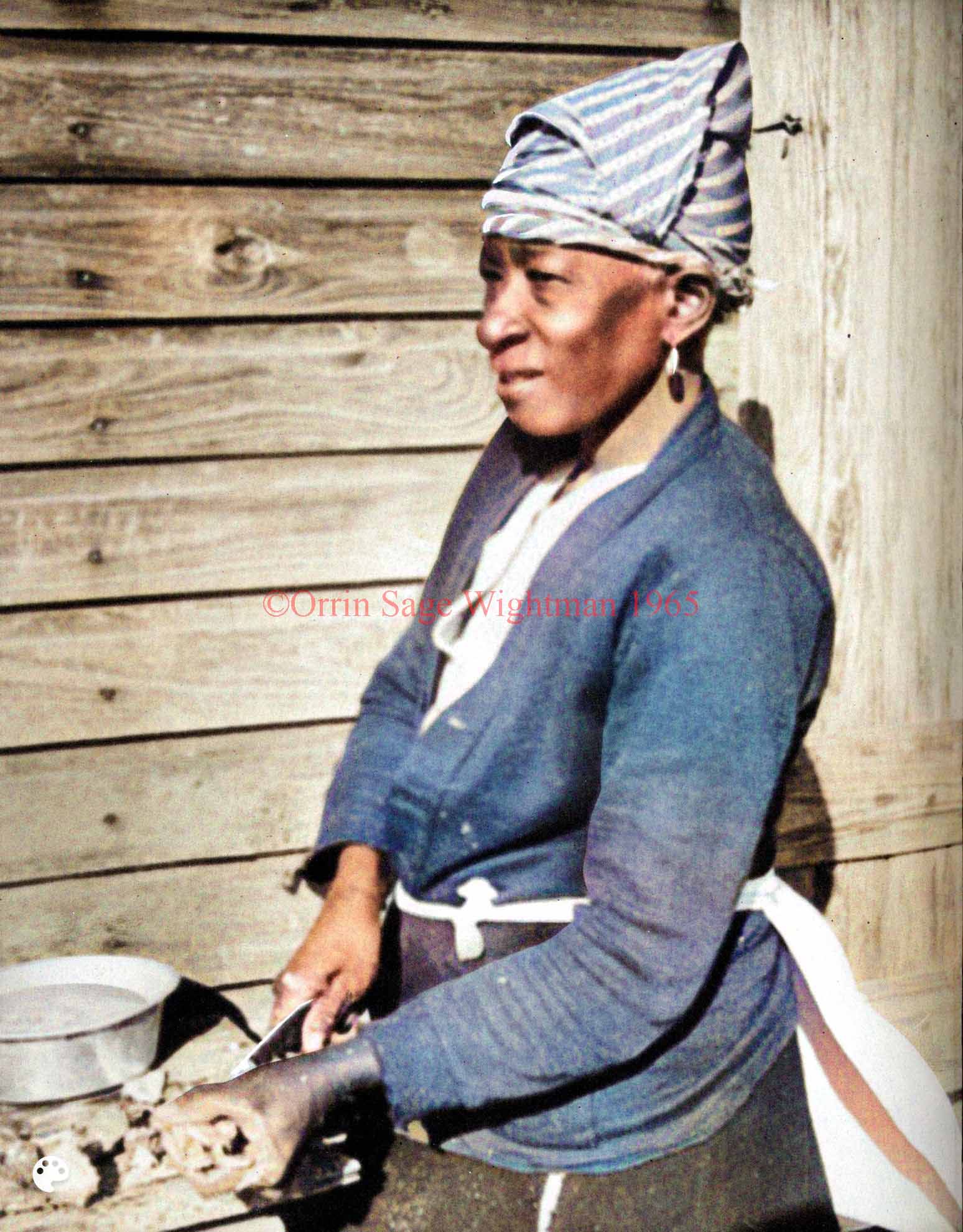

| Dido, a Rice Field Worker |

123 |

| Fort King George |

125 |

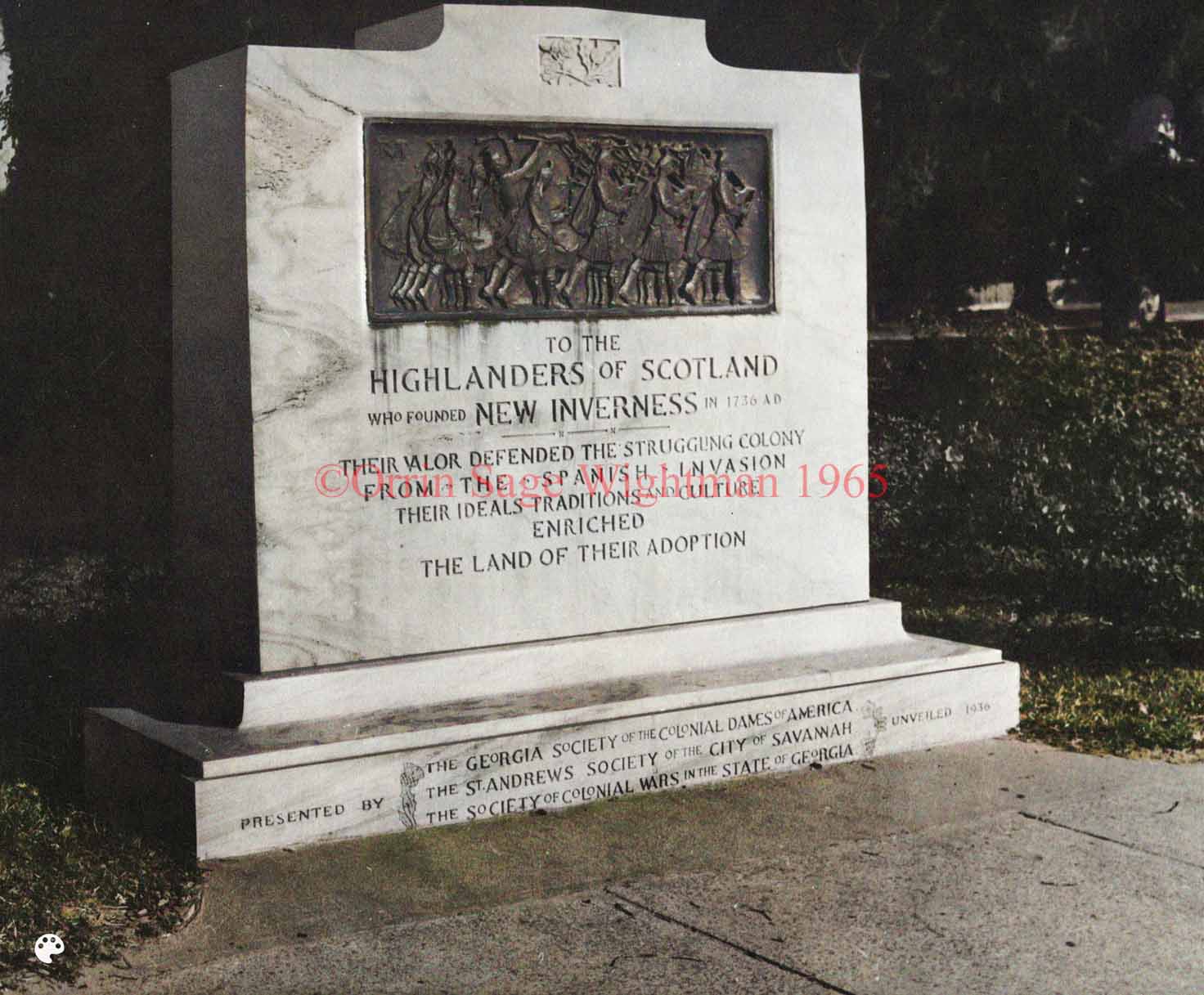

| The Highlanders of Darien |

127 |

|

Ashantilly |

129 |

| Downey Home, the Ridge, Darien |

131 |

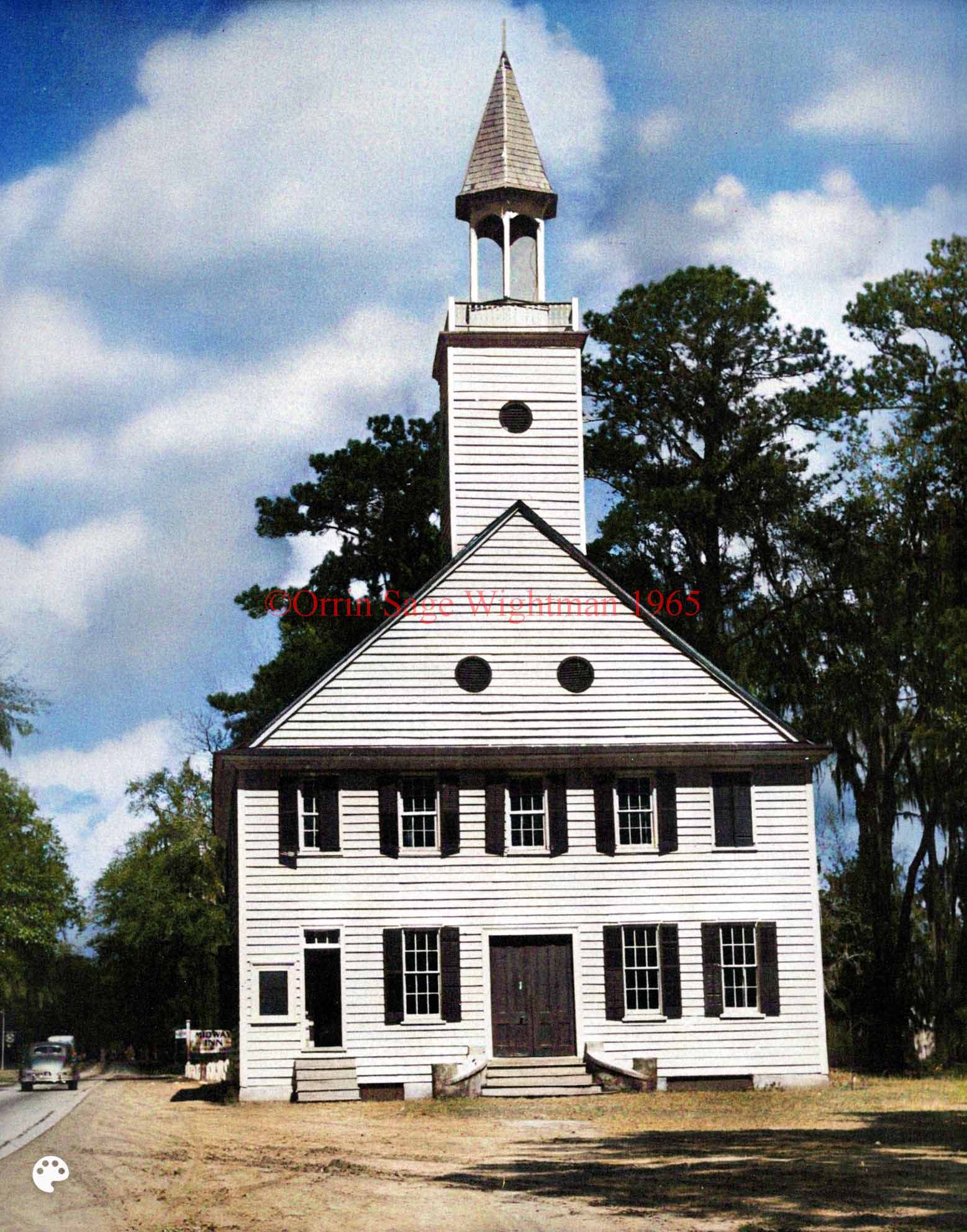

| Midway Church |

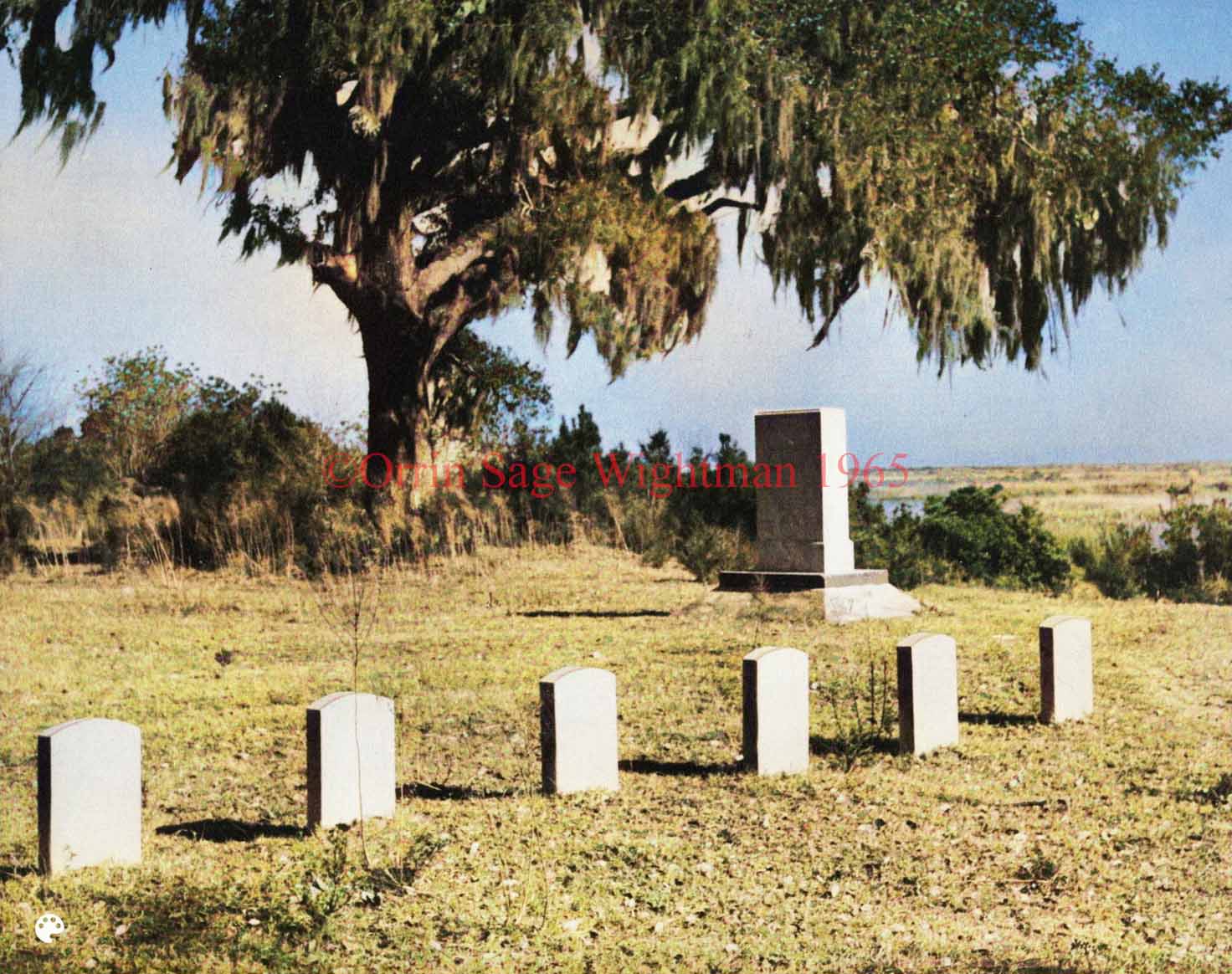

133 |

| Midway Cemetery |

135 |

| Old Screven House at Sunbury |

137 |

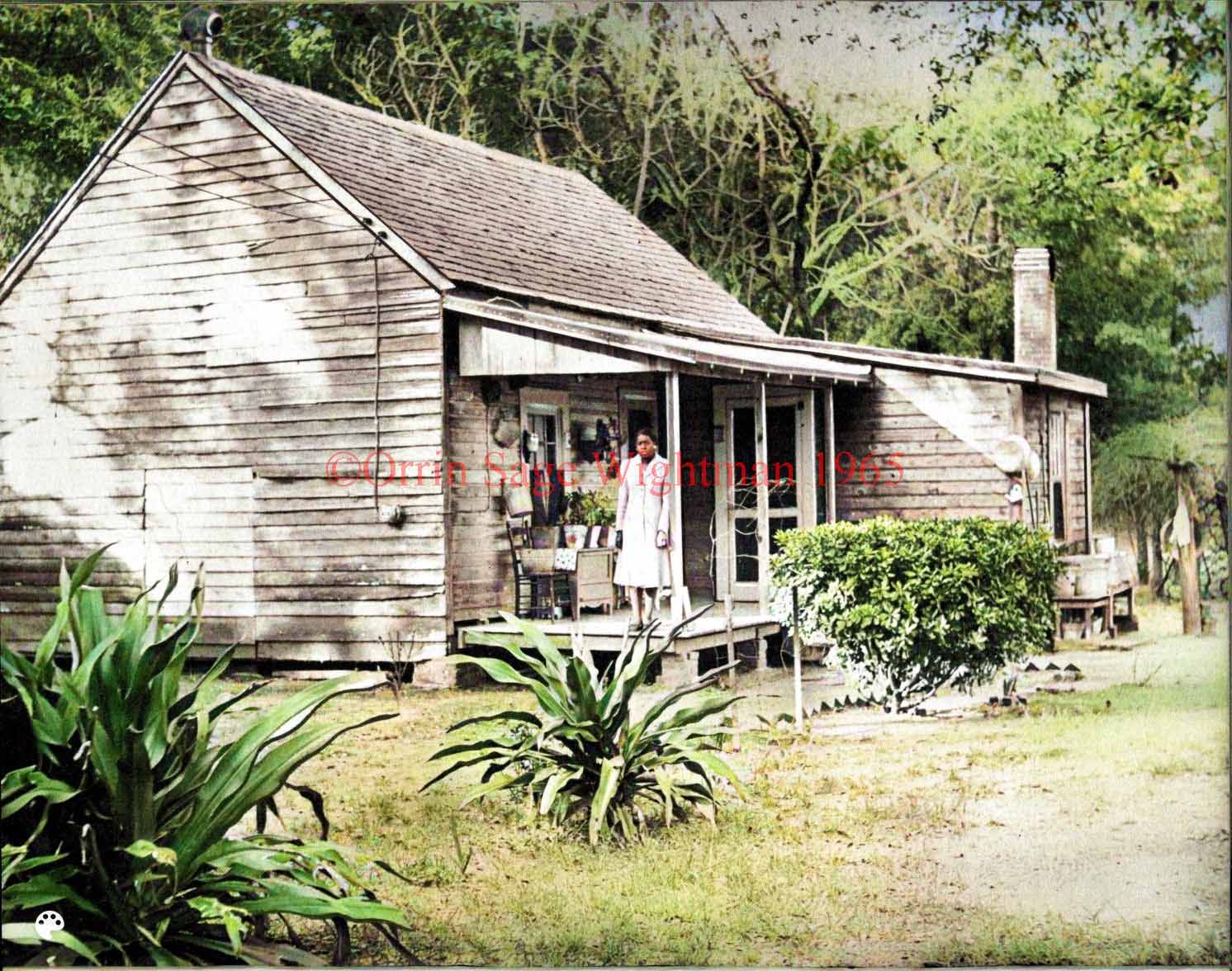

| A Negro Home in Jewtown |

139 |

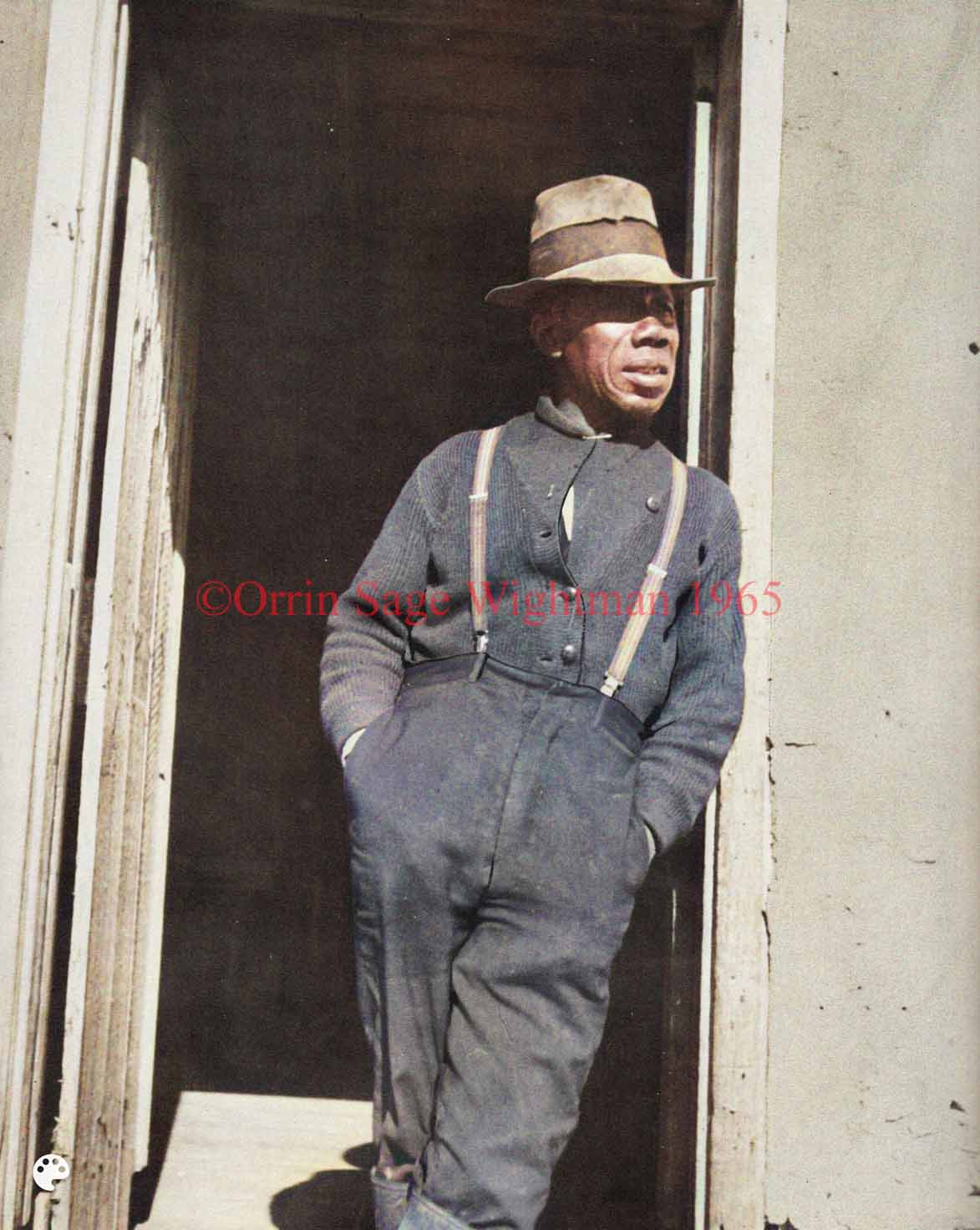

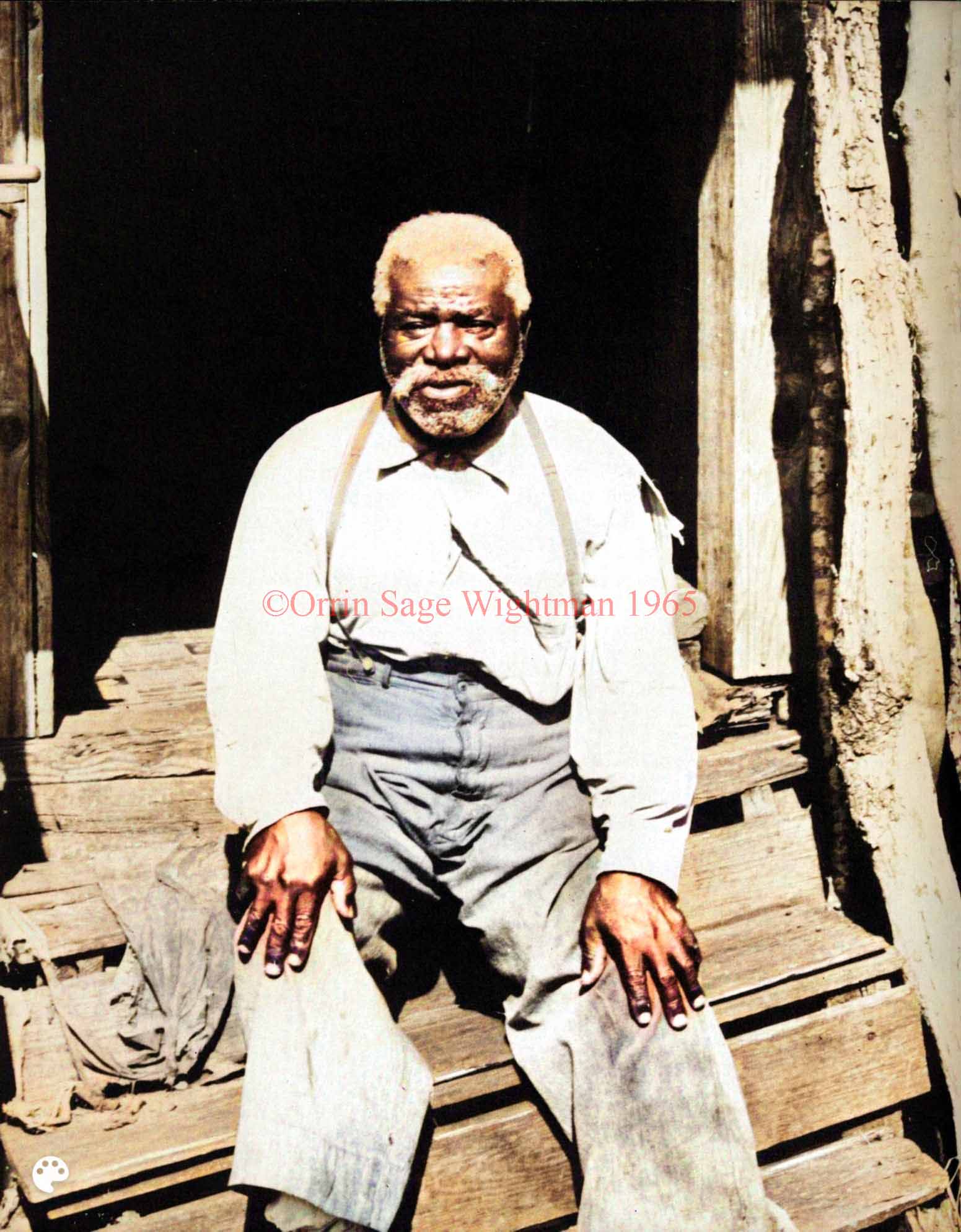

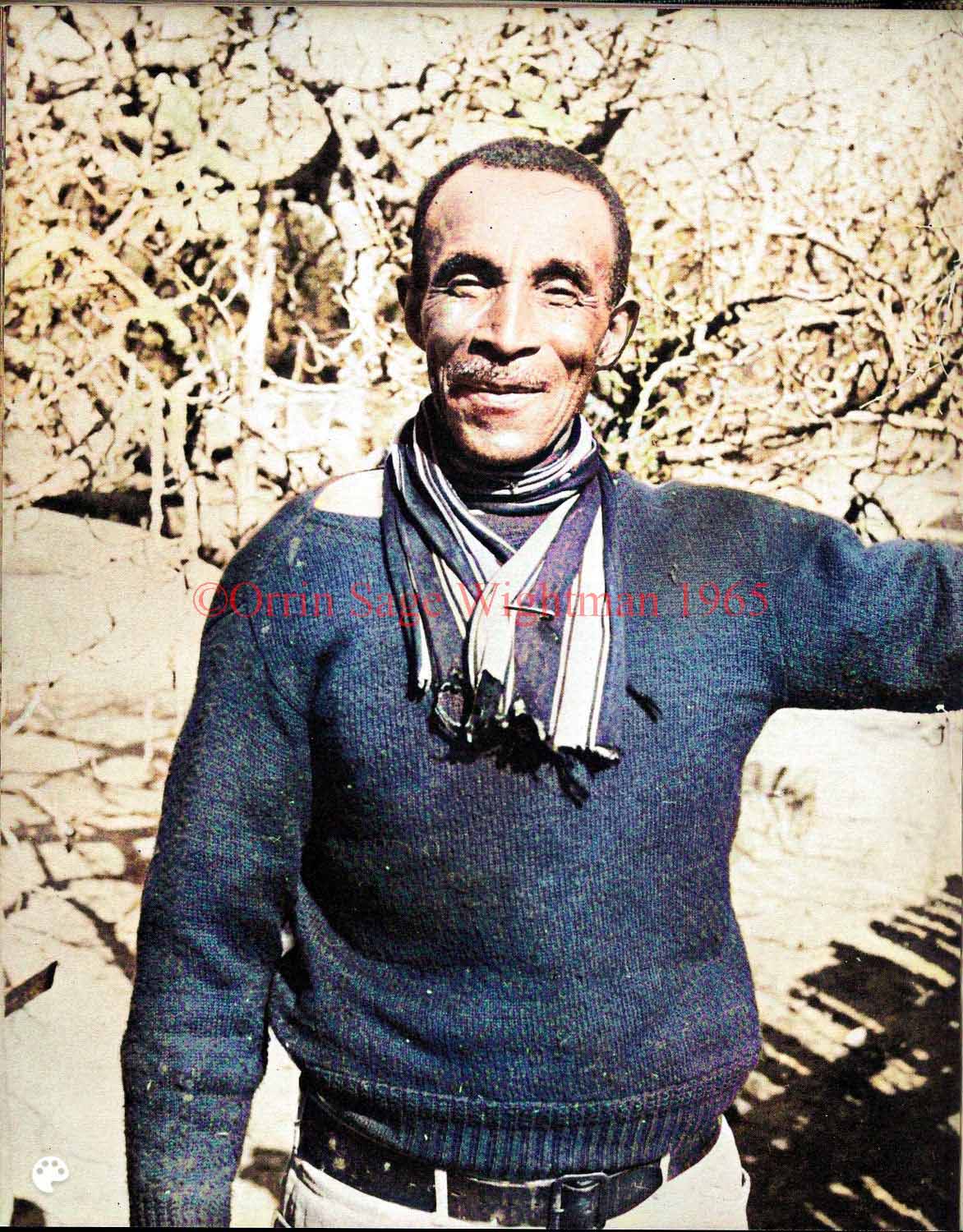

| Bacchus Magwood |

141 |

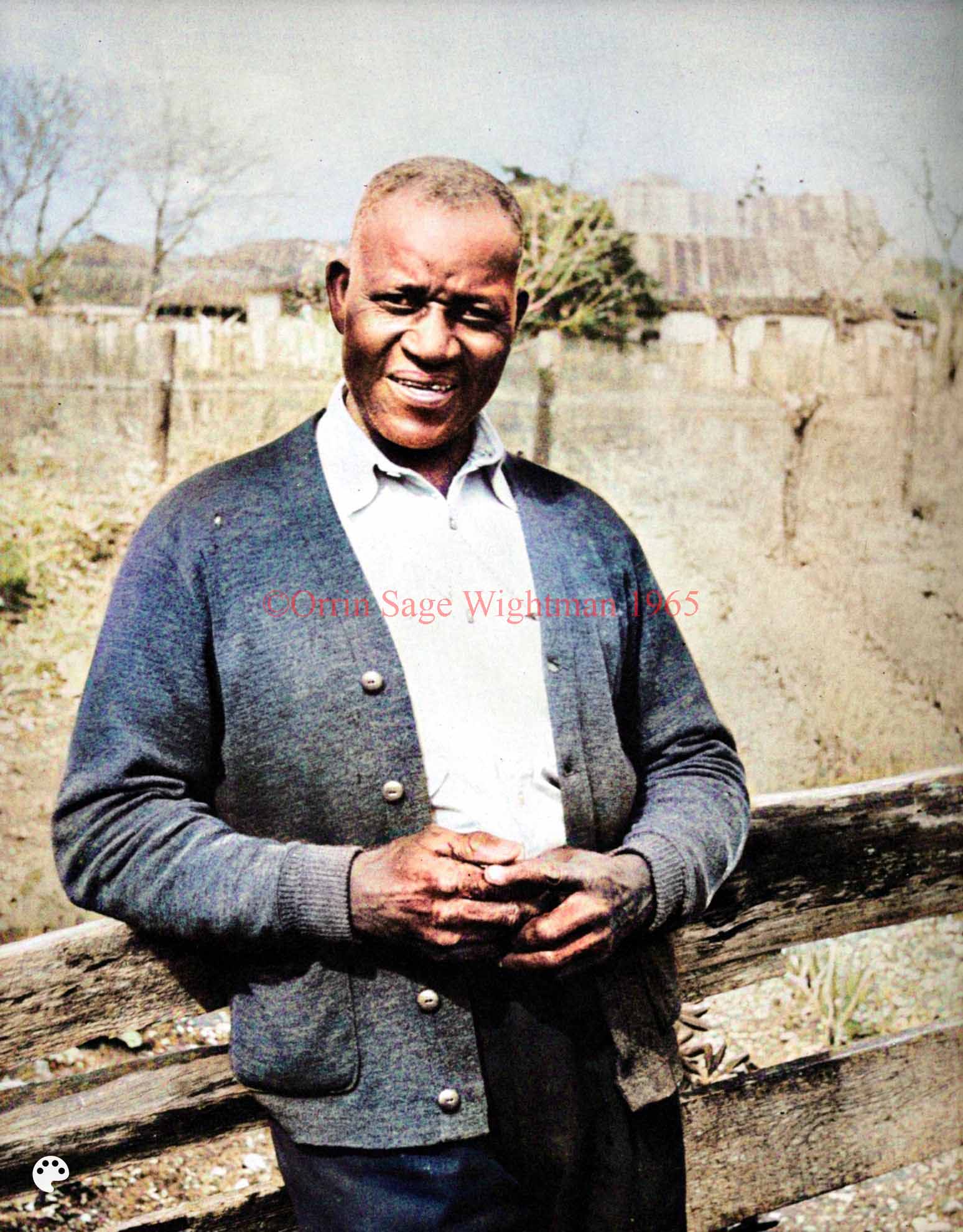

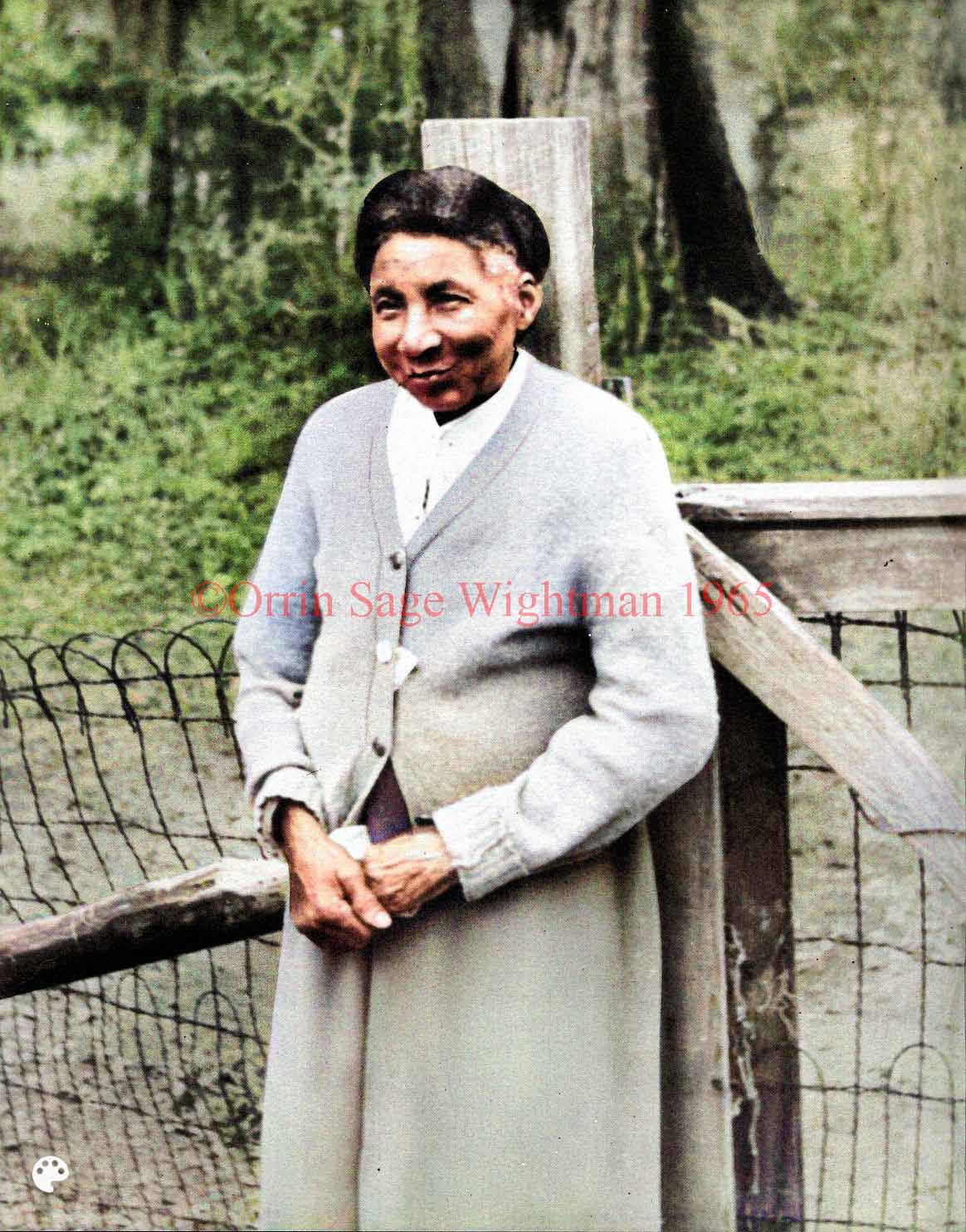

| Willis Proctor |

143 |

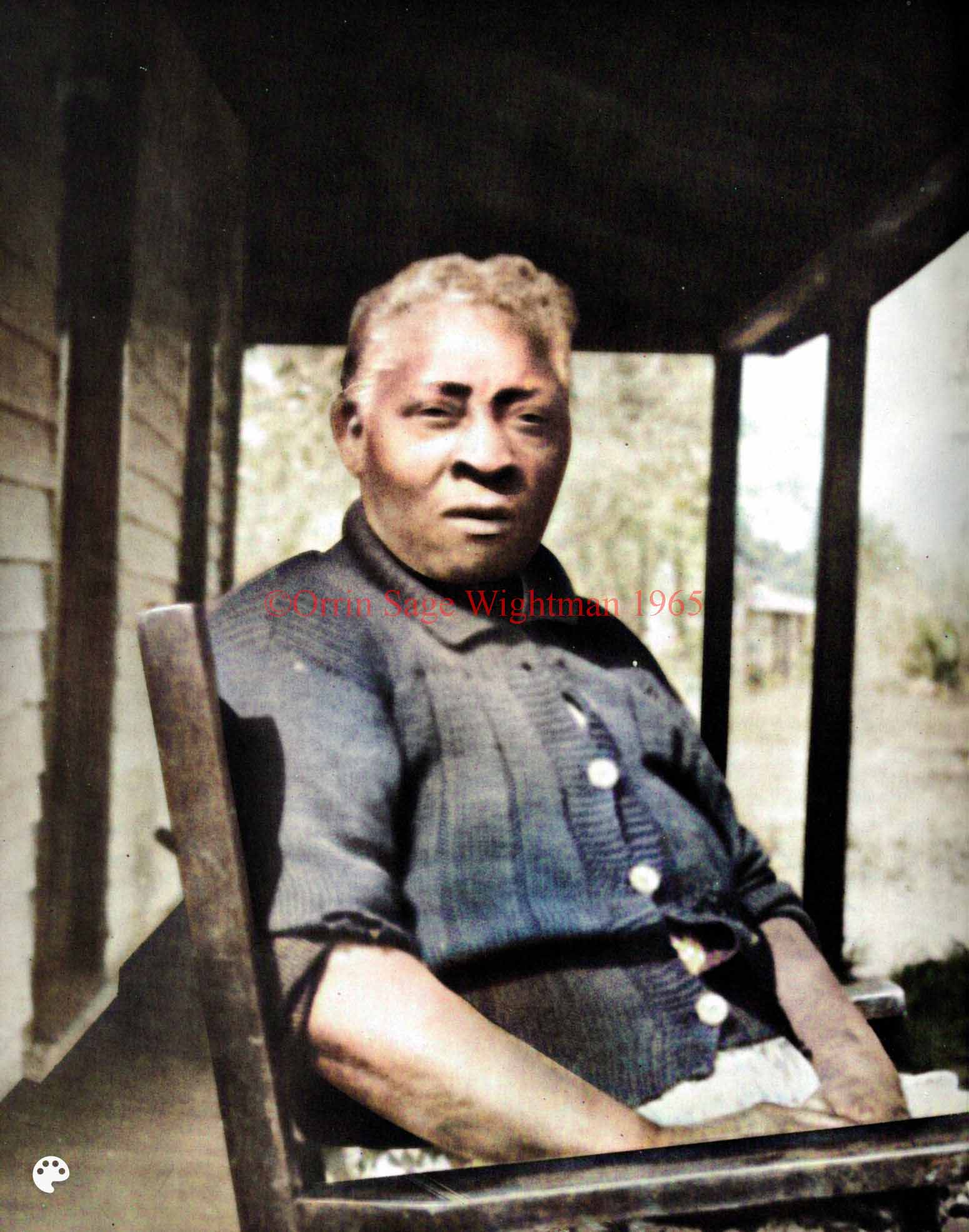

| Julia Armstrong |

145 |

| Joe Armstrong |

147 |

| Edith Murphy |

149 |

| The House that Neptune Built |

151 |

| Lavinia Abbott |

153 |

| Ben Sullivan |

155 |

| Charles Wilson, the Basket Maker |

157 |

|

Pg. 9

Blank

Pg. 10

Blank

Pg. 11

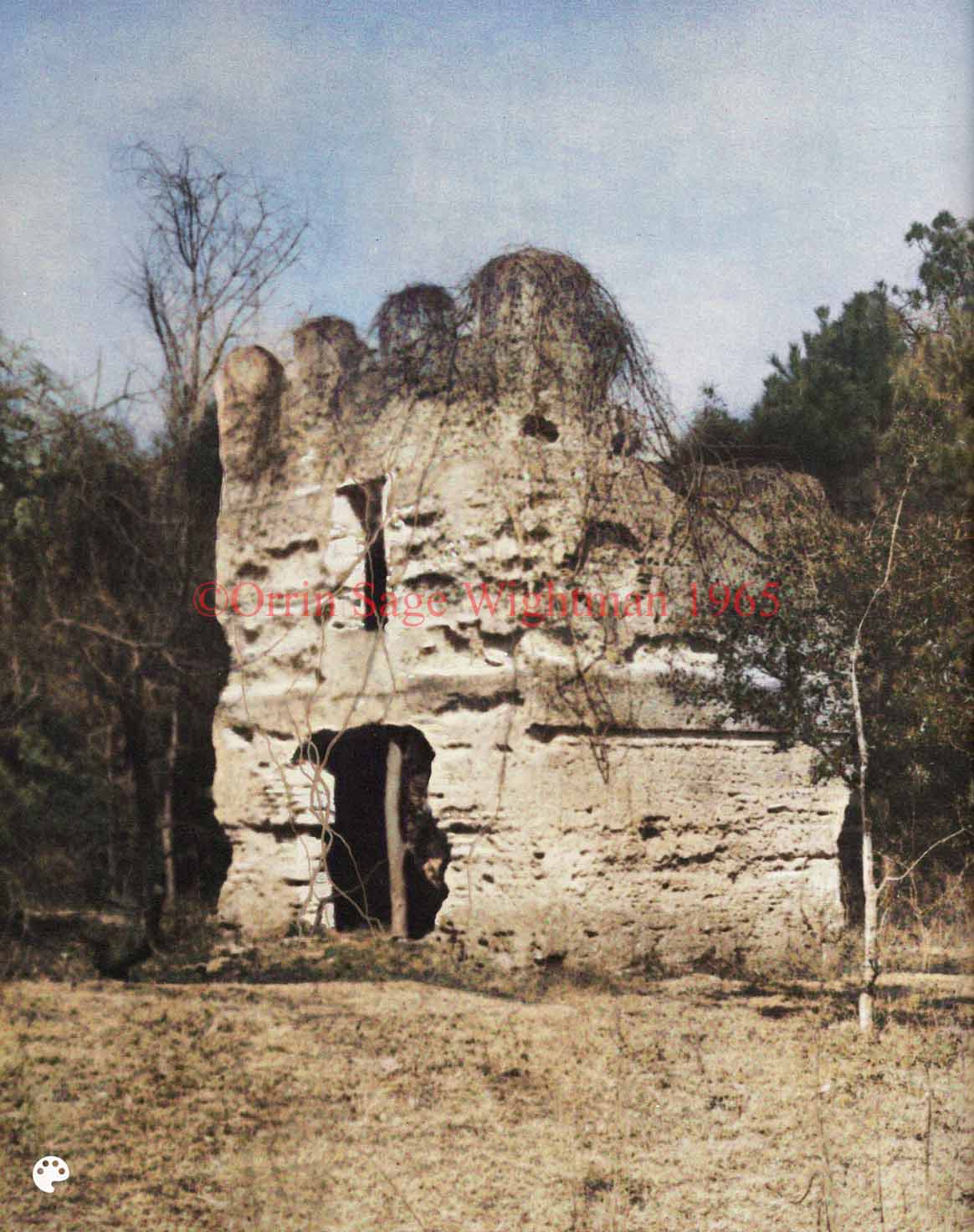

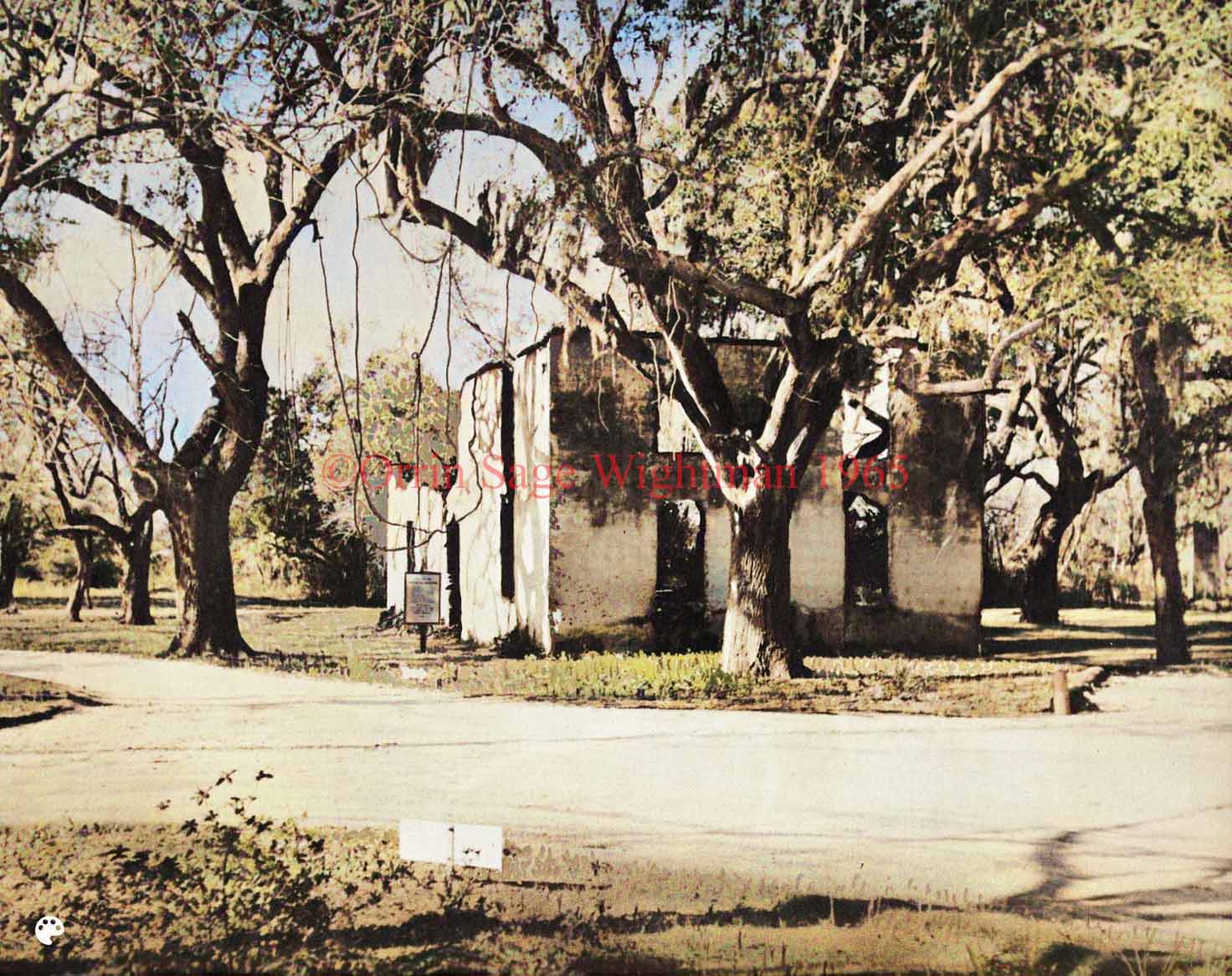

Fort Frederica, St. Simons Island,

Georgia

Built in 1736 by British settlers

under the direction of James Edward Oglethorpe, founder and

first Governor of Georgia, Fort Frederica was the most expensive

fortification built by the British in North America and became the

military headquarters of this Southern Frontier for Britain’s

Colonies in the New World against the Spaniards in Florida.

Oglethorpe named this place Frederica in honor of

Frederick, Prince of Wales, son of George II and

father of George III. Augusta was named in honor of the

Princess of Wales, while the naming of Cumberland Island and Amelia

Island honored William, Duke of Cumberland, and Amelia,

other children of the royal family.

Located on the western shore of St. Simons Island on

Frederica River, a part of the Inland Waterway which was the route

followed by coastwise vessels, this site was chosen by Oglethorpe

for his great fort because of its strategic position. Here the

river bends and turns so that an approaching vessel would be exposed

to the cannon of the fort without being able to return the fire.

Fort Frederica, a star-shaped work with four bastions

and walls of tabby faced with earth on the outside, was surrounded

by a moat, which was further protected by palisades. Oglethorpe

wrote that in the building of the fort he followed the plan of M.

Vauban, the great military engineer of France, whose work had

revolutionized the art of warfare.

Inside the fort there were several buildings of brick

and of tabby which were used as storehouses. The ruin of the

building shown here is “all that Time has spared” of these buildings

though tabby and brick foundations give evidence of the location of

others.

Another fortification, Fort St. Simons, was located at

the South End of St. Simons Island. A regiment of 650 British

soldiers, brought over in 1738, manned both of these fortifications

as well as the other forts and outposts in this area.

Fort Frederica was built for a purpose and it gloriously

achieved that purpose; its defenders turned back the tide of the

Spanish invaders and made this area secure for Britain.

Pg. 12

Pg. 13

Fort Frederica in the War of Jenkins’

Ear

The struggle between Spain and

England for control of this southeastern section of our country was

a part of the conflict which is generally known as the War of

Jenkins’ Ear. After the defeat of the Spaniards in the Invasion of

1742 and the termination of the war by the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle

in 1748, the regiment of British soldiers stationed here was

disbanded and Fort Frederica was abandoned.

As the houses fell into ruins, settlers from other parts

of St. Simons took away the bricks and pieces of tabby to use in

buildings they were erecting. The tabby walls of the Fort were

sawed into blocks and used in the first St. Simons Light House. As

time went on, this abandoned Frederica property came into the

possession of Capt. Charles Stevens, a native of Denmark, who

operated a coastwise sailing vessel on the Inland Waterway. Capt. Stevens built a home for his family on top of the building

shown here. Later, the Stevens family occupied a house

located a short distance east.

In 1903 the president of the Georgia Society, Colonial

Dames of America, was Mrs. Georgia Page King Wilder who had

been born at Retreat Plantation, St. Simons, and had known of Fort

Frederica and its history all her life. Through Mrs. Wilder’s

friendship with Mrs. Belle Stevens Taylor, who now owned this

land, Mrs. Taylor gave this building and a small piece of

ground surrounding it to the Georgia Society of the Colonial Dames

of America, who repaired the ruins and rebuilt this room shown in

the picture. The large pieces of tabby lying on the ground were

placed in their original position and the ceiling of the room

rebuilt with new brick. The other room located on the right still

has its original ceiling of old English brick brought from England

in 1736. So to the Georgia Society of the Colonial Dames of America

goes the honor of having saved this ruin from destruction.

Through the efforts of

Judge and Mrs. S. Price

Gilbert and Mr. Alfred W. Jones of Sea Island, the Fort

Frederica Association was organized in 1941 and funds were raised

for the purchase of the lands occupied by the old Fort and the Town

of Frederica. In 1947 this area was formally dedicated as Fort

Frederica National Monument.

Pg. 14

Pg. 15

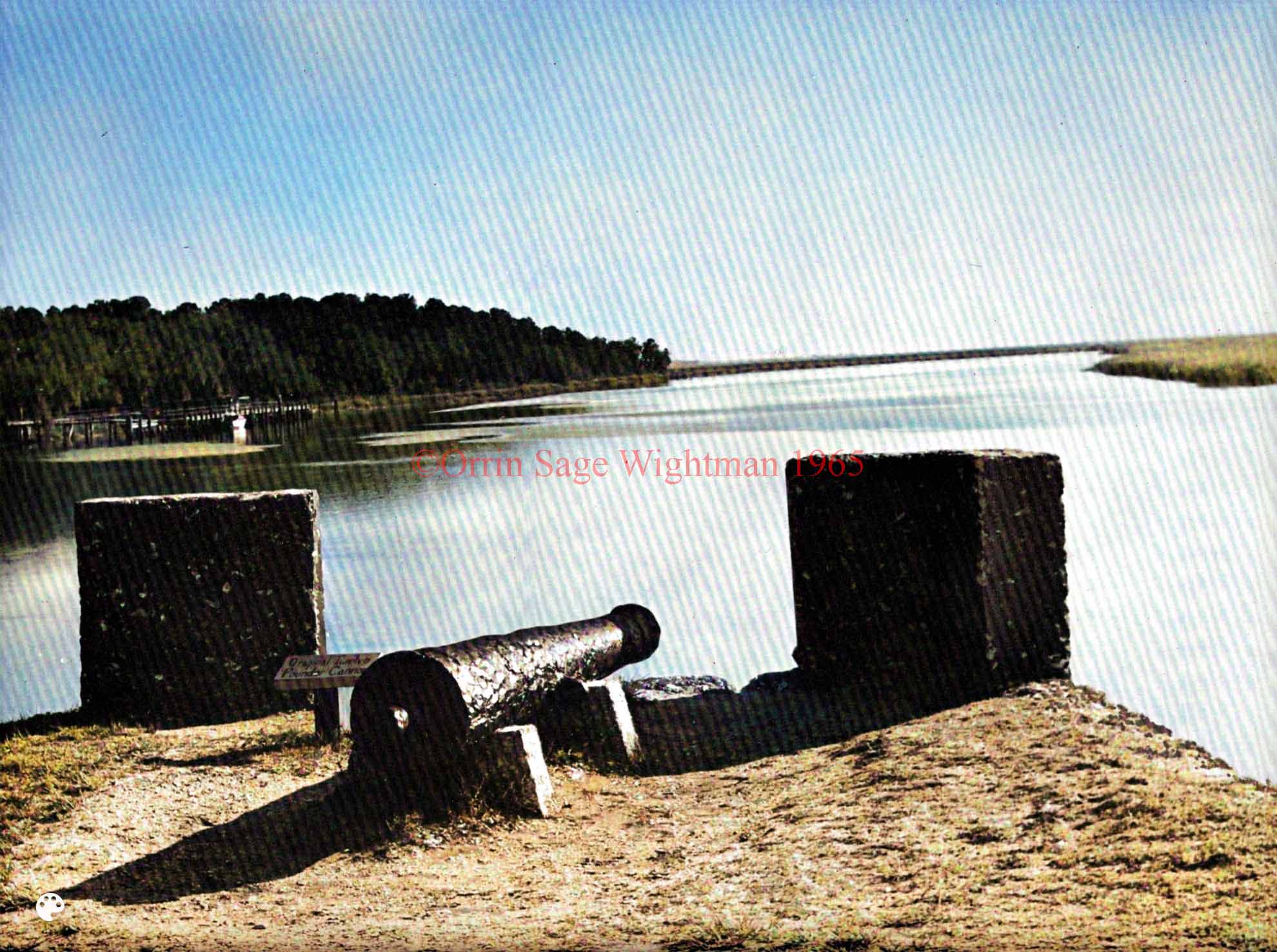

Old Frederica Cannon

This old cannon is the only one of

the original Fort Frederica cannon still here. It is what was known

as a twelve-pounder, the size of the cannon being determined by the

weight of the cannon ball. When in use, this gun was mounted on a

wooden carriage so that it could be moved from place to place. It

is believed that it was never mounted on top of this building. When

the Colonial Dames acquired this ruin, the cannon was on the ground

near the southeast corner. In order to protect it more adequately

it was placed on top of the building.

In its day Fort Frederica had many cannon.

Oglethorpe’s first engineer at Fort Frederica was Samuel

Augspourger, a Swiss emigrant who had come to Purysburg, S.C.,

and from there to Georgia. Augspourger wrote that there were

fifty cannon at Frederica, some of them being eighteen-pounders.

His map made in 1736 (original manuscript in John Carter Brown

Library, Providence, R.I.) shows the “spur work” on the river where

the cannon…are on a level with the water’s edge, and make it

impossible for any boat or ship to come up or down the river without

being torn to pieces…” Other cannon were mounted on the bastions of

the fort and at the Point Battery located on the lower part of the

bluff.

Even after Fort Frederica was abandoned, a guard was

stationed here to protect the place and prevent the guns from being

taken away by pirates. In 1755 a dozen twelve-pounders that had

been mounted in the “spur work” were removed and carried to Cockspur

Island in the Savannah River where they were used to fortify Fort

George. During the Revolutionary War some of the Frederica cannon

were taken to Sunbury and used in fortifying Fort Morris, but this

one has been here at Frederica for more than two centuries.

Fort Frederica was so well situated that the Spaniards

never succeeded in attacking it, so its cannon were never fired

except on special occasions, one of which was the salute to Gen.

Oglethorpe when he returned from a voyage to England.

Pg. 16

Pg. 17

The Barracks Building

This barracks building, erected to

house the soldiers of Oglethorpe’s Regiment, was ninety feet

square, had a shingle roof, and was built in the form of a hollow

square with the rooms opening on a court yard. The only part of the

building which was two stories high was this tower on the north side

containing the entrance to the building.

In addition to the accommodations for the soldiers,

there were facilities for the hospitalization of the troops and

quarters for political prisoners.

One of the famous prisoners incarcerated here was

Christian Priber, who for some years lived among the Indians in

the upper part of South Carolina. There he attempted to set up a

communistic form of government, a Utopia which he called “Paradise,”

and designated himself as its Prime Minister.

In 1743 Prime Minster

Priber was captured by the

British, brought to Frederica, and incarcerated there. During his

imprisonment the magazine at the fort exploded. With bombs flying

through the air in every direction, the officer in charge threw open

the doors of the prison and told the occupants to flee for their

lives. When the danger had passed and the people returned to

Frederica, inquiry was made as to the whereabouts of Priber

whom no on had seen during the excitement. A search disclosed that

the Prime Minister of Paradise had not left his prison but had

stayed there taking refuge under a feather bed!

Charles H. Fairbanks, Archeologist of the

National Park Service, recently excavated the area covered by two

rooms of the barracks building. One of these was the kitchen in

which were found pieces of dishes, spoons, and other ware used by

the soldiers. A most interesting item was the brass name-plate from

the gun-stock of Capt. William Horton’s gun. Horton,

who came to Frederica with Oglethorpe I n1736, had a

plantation on Jekyll Island, and in time became an officer in Oglethorpe’s Regiment, going from lieutenant to major. When

Oglethorpe finally returned to England, Horton succeeded

to the command of the military forces in this area.

Pg. 18

Pg. 19

The Town Moat

Adjoining Fort Frederica on the

east lay the Town of Frederica, which was half a hexagon in shape

and contained eighty-four lots on which the Frederica settlers built

their homes.

After the outbreak of war with Spain in 1739,

Oglethorpe strengthened his defenses by fortifying the town. It

was enclosed within a moat two-thirds of a mile long which was

flooded by tidal water fro Frederica River, the moat touching the

river at either end. At the corners of the moat were bastions, on

each of which was a two-story tower capable of holding a hundred

men. Flanking the moat on either side were palisades while the

walls of the moat formed the ramparts of the town.

In the center of the east wall of the town was located

the Town Gate over which was a tower containing sentry boxes.

Leading from this tower was the bridge over the moat which gave

entrance to the Town of Frederica. This entrance on the east was

known as the “Landport,” while the western entrance located near the

river was called the “Waterport.”

Oglethorpe sometimes used the moat for target

practice. In 1743 when he was preparing to invade Florida, the

soldiers who were to make the invasion “…marched out of the Town,

and each Platoon fir’d at a Mark, before His Excellency for the

Prize of a Hat and Machet, to the Man who made the best Shot at an

hundred yards Distance, in the Fosse round the Fortifications. He

afterwards gave Beer to the Soldiers…”

During the centuries which have passed the moat was

abandoned, great trees of pine and live oak have grown up on its

banks. Today, their moss-draped forms present a peaceful scene

which is very different from that contemplated when the threat of

the Spanish Invasion brought about the construction of the moat.

Pg. 20

Pg. 21

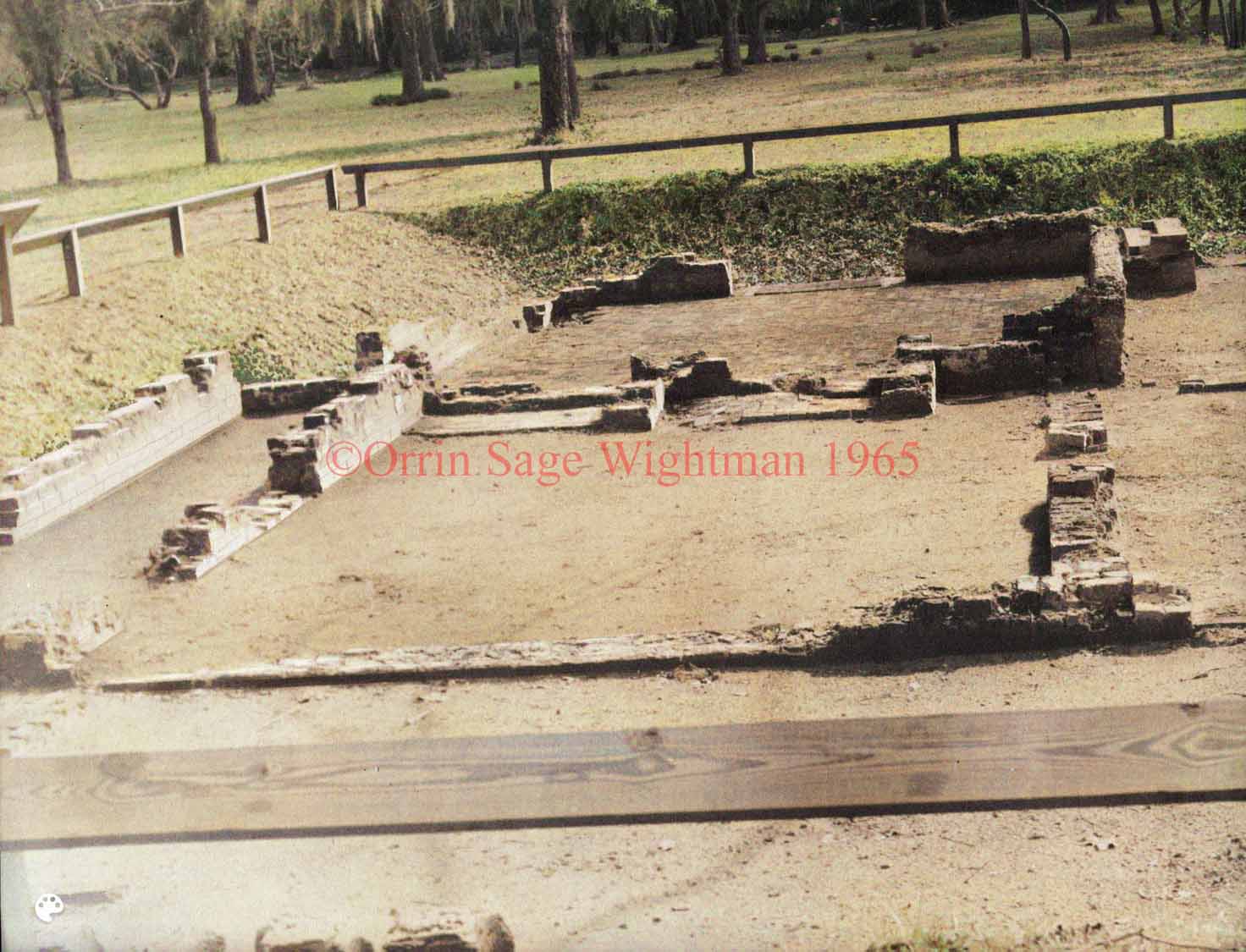

Foundations of Frederica’s Old Houses

During the Military Era the old

Town of Frederica was a thriving settlement. Its streets were lined

with houses built of tabby, of brick, and of wood. Some were

substantial dwellings, two were log cabins, and some were described

as “huts.”

Here the settlers lived and conducted their businesses,

which included taverns, an apothecary shop, and several stores, in

one of which iron goods were sold. Among the trades and professions

represented were those of shoemaker, cordwainer, brazier,

husbandman, dyer, tallow candler, baker, tanner, coachmaker,

carpenter, bricklayer, woodcutter, blacksmith, millwright, miller,

pilot, accountant, surveyor, recorder, magistrate, tithingman,

constable, doctor, and officers of Oglethorpe’s Regiment.

After the Regiment was disbanded, Frederica became a

“dead town.” The shopkeepers and professional men who had depended

on the soldiers for their livelihood had no customers. Abandoned by

their owners, the houses fell into decay, the brick walls tumbled,

and the brick and tabby were hauled away to be used in buildings

erected on other parts of St. Simons and by a new generation of

settlers. New families came to live on the site of the old Town and

every trace of its buildings and streets was lost. Gone, also, were

the beautiful orange trees that had line Broad Street. It was only

in musty records that this old town lived.

Through old maps and the letters and records of these

first settlers it has been possible to locate the town lots and

streets, and through archeological excavations to prove that these

homes had existed. In 1952 this program was inaugurated under the

direction of Charles H. Fairbanks, Archeologist of the

National Park Service, who excavated lots #1 and #2 of the South

Ward.

The rooms in the foreground of this picture were in the

house on lot #1 which was the home of Dr. Thomas Hawkins, the

medical doctor for the Frederica community; later, the surgeon of Oglethorpe’s Regiment. To the left can be seen the walls of the

stairwell for the outside stairs which led to the Hawkins’

front door on the main floor. In the background can be seen the

brick of the floor in the Davison house located at lot #2.

Pg. 22

Pg. 23

Hawkins-Davison Houses

With all the lots in Frederica

available, it was decided to excavate these two houses first because

they were built with a common wall which lay along the line between

the lots. By locating this wall it would be possible to fix the

location of all the lots in the old town. These houses, built of

brick and three stories high, were among the best of the Frederica

houses. Lot #1 had been granted to Dr. Thomas Hawkins, who,

with his wife, Beata, accompanied the first settlers to

Frederica.

Lot #2 was granted to

Samuel Davison, who with

his wife, Susannah, and their year-old daughter, Susannah,

was also among the first settlers. Later, the Davisons had

two more children born here. Davison was a “chairman” and

was brought over at this time because, in addition to making

carriages, he “had been bred to making stocks for guns.” Although

Davison was a Presbyterian, John Wesley said he was

one of the best of his parishioners. He was a “good Samaritan” to

Charles Wesley, nursing him during a severe illness. Davison kept a tavern in his house but said he never suffered

“any disorderly meeting or late hours.” The floor shown in this

picture was in his kitchen; and, as it had been set in tabby mortar,

the bricks are still in place.

During the excavation of these buildings many

interesting artifacts were found that told of the way of life of

these people. In the Davison house were hundreds of pieces

of dishes, clay pipes, bottles, and other items to be expected in a

tavern. The excavations also showed that Davison had a

well-built house. The inside of this room was finished with a

“studding” on which were nailed laths to which plaster was applied.

The

Hawkins house, however, was of cheaper

constructions, the plaster being applied directly to the brick

walls. Also, the brick of the floor, set in sand, has been carried

off along with the brick of the walls. In this house were found

some fine pieces of porcelain with the gold decoration still intact;

also, bottles of many sorts—a snuff bottle, an ink bottle, medicine

bottles, ointment jars, and an enema tube made of ivory. Just what

you would expect to find in a doctors house.

As these houses and furnishings were in sharp contrast,

so were the families. Everyone spoke well of the Davisons,

but the Doctor’s wife was known as a mean woman; in fact, it was she

who made life so miserable for John and Charles Wesley.

Pg. 24

Pg. 25

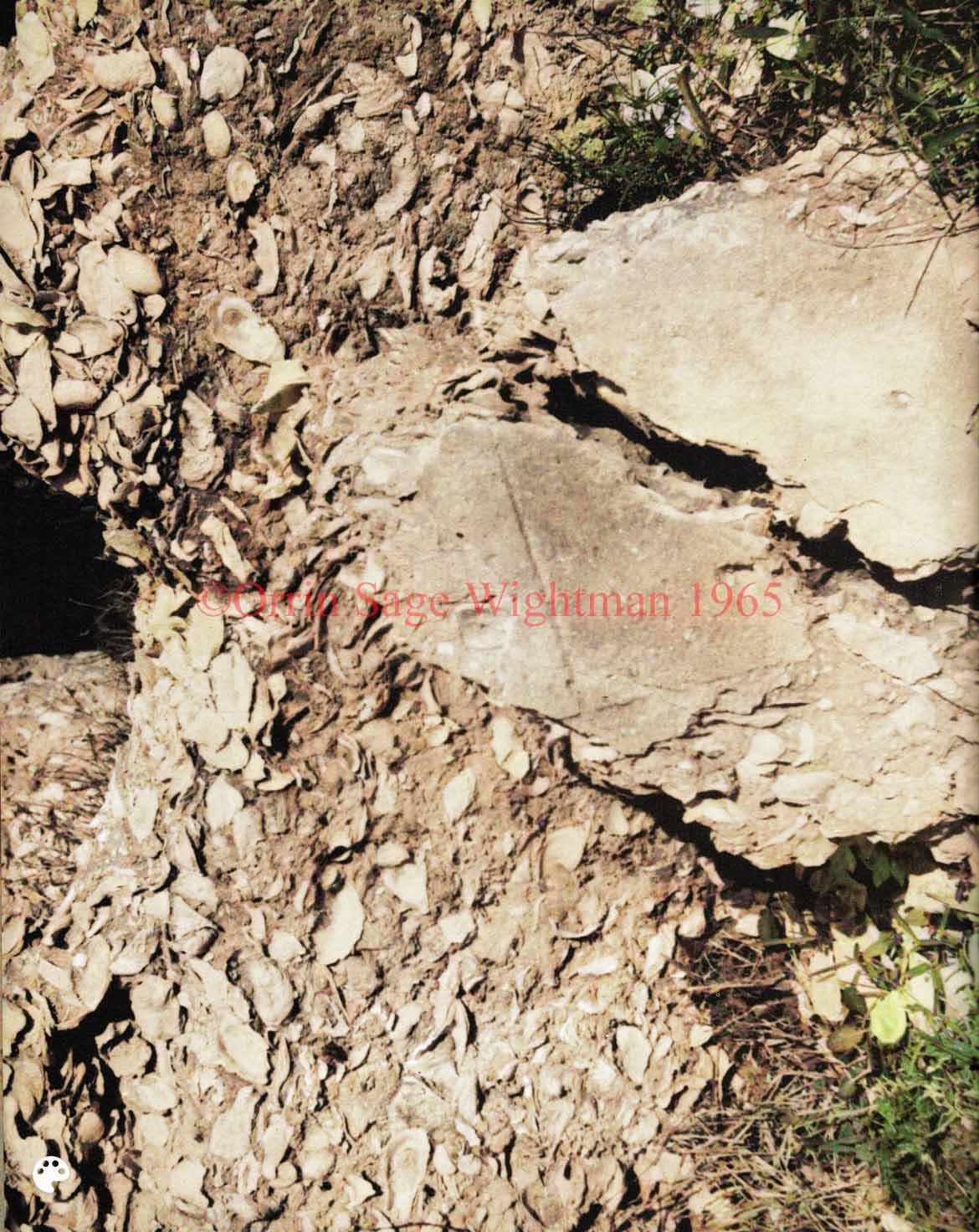

Tabby

Tabby was the building

material for walls, floors, and roofs widely used throughout this

section during the Military Era and the Plantation Era. It was

composed of equal parts sand, lime, oyster shell and water, mixed

into a mortar and poured into forms. Those forms were set up just

one board high and for the entire outline of the building, being

held firmly in place and the proper distance apart by wooden pins.

The mortar was poured into the forms, firmly packed, and

allowed to harden. The wooden pins and forms were then removed and

placed in position for the next layer, and so on until the walls

reached their full height. The pouring of two layers a week was

considered good work.

After the tabby walls were completed, they were given a

stucco finish of mortar made of lime and sand. This was considered

necessary in order to make the buildings water-proof since tabby was

very porous and absorbed water readily; this coat of stucco also

covered the streaks which showed the width of the boards used as

forms, and the round holes made by the wooden pins.

The lime used in tabby was made by burning oyster shell

taken from Indian Shell mounds or “Kitchen Middens,” the trash piles

of the Indians. Into the lime kilns were piled wood and oyster

shell, layer on layer, into a great mound, with as much as two

hundred to three hundred bushels of shell at each burning. When it

was time to start the fire, musicians would appear and food and

drink were brought forth. Indeed the affair was a festive occasion

that, as a social community gathering, ranked with cock fights and

wrestling matches or celebrations of the King’s Birthday and of St.

Andrew’s Day. Some of the men watched the fire throughout the night

and the resulting pile of powdered shell was lime. The Lime Kiln on

St. Simons was south of the German Village and about four miles from

Frederica.

The word

tabby is African in origin, with an

Arabic background, and means a wall made of earth or masonry. This

method of building was brought to America by the Spaniards.

However, when the coquina (shell-rock) quarries near St. Augustine

were opened, hewn stone superseded tabby for wall construction

there. Coastal Georgia has no coquina, so tabby continued to be

used here even as late as the 1890’s.

Pg. 26

Pg. 27

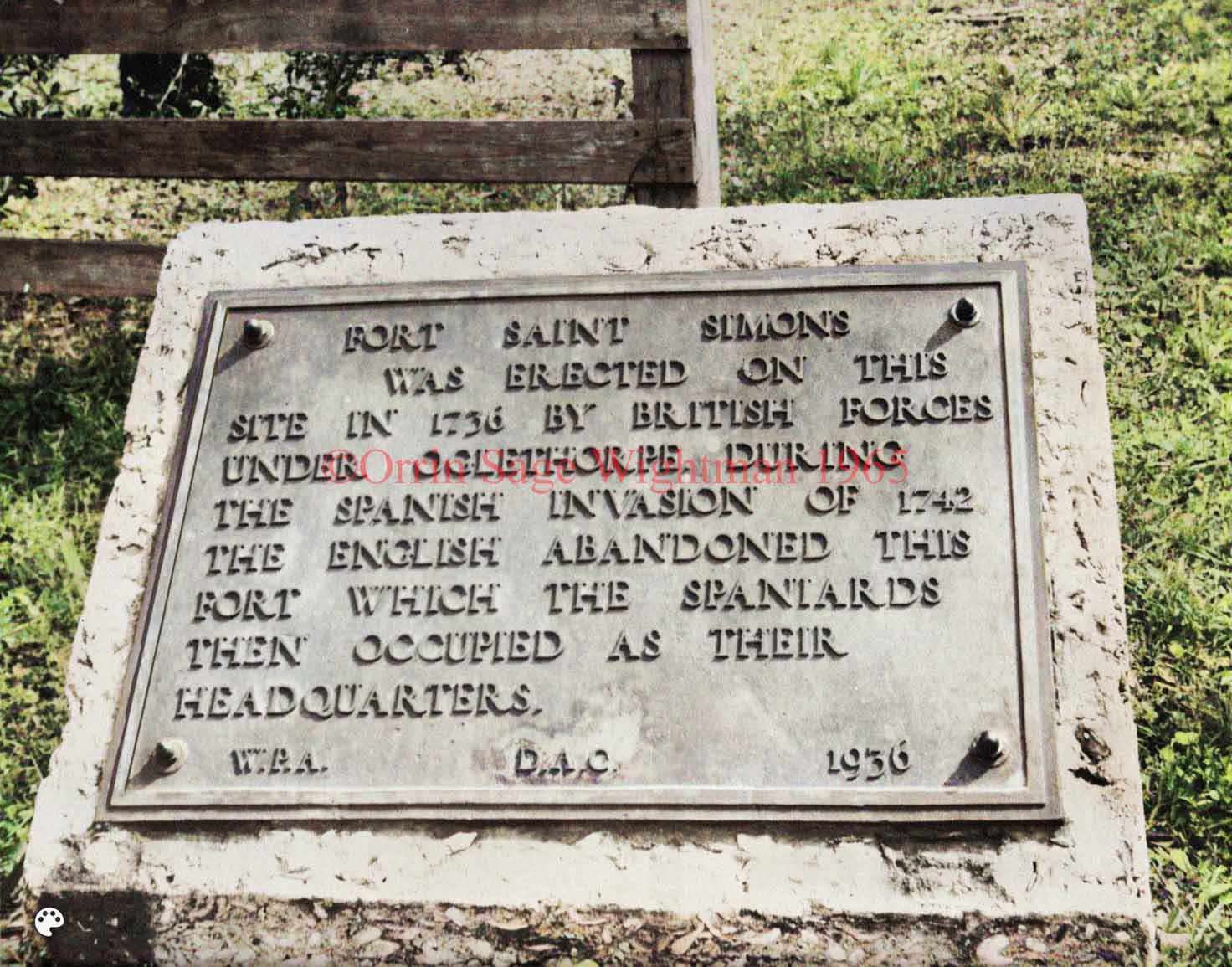

Fort St. Simons

A few weeks after the Frederica

settlers reached St. Simons and established themselves in their new

home, a group of thirty soldiers arrived here. These were part of

the Independent Company who had been stationed at Port Royal, S.C.,

under the command of Lieut. Philip Delegal.

Oglethorpe posted them on the southeast point of

St. Simons at a place which projected into the sea so that the

position commanded the entrance to the harbor. He chose this site

because all ships that came in must pass “within shot” of this

place, “the channel lying under it by reason of a shoal that runs

off from Jekyll Island.”

This was known as

Delegal’s Fort at Sea Point and

was fortified “with gabions filled with sandy earth,” between which

were mounted thirteen cannon: in a short time the garrison numbered

one hundred men.

Oglethorpe then went back to England to obtain

the necessary men and equipment to fortify Georgia adequately,

returning in 1738 with a regiment of 650 British soldiers. Oglethorpe was named Colonel of this regiment and General and a

Commander-in-Chief of the military forces of South Carolina and

Georgia.

A larger and stronger fortification, known as Fort St.

Simons and sometimes called the Soldiers’ Fort, was now built here

and the soldiers of the Independent Company stationed at Delegal’s Fort were taken into the regiment. At this tie

British regiments were not numbered, the only designation used being

Oglethorpe’s Regiment.

The area around Fort St. Simons presented the appearance

of a neat village, with streets regularly laid off, and with more

than one hundred clapboard houses occupied by the soldiers and their

families.

The land occupied by

Delegal’s Fort and Fort St.

Simons has been washed away, leaving no trace of either.

Pg. 28

Pg. 29

Marker on Military Road

As soon as the Independent Company

was stationed at Delegal’s Fort at Sea Point, Oglethorpe

arranged that “a communication was opened with Frederica,” a

distance of about nine miles. No doubt this path followed an Indian

trail and was sufficient for the needs of that time, but it could

not have been very well marked. On his third visit to Frederica,

John Wesley and his friend, Mark Hird, walked from

Frederica to Delegal’s Fort and on the return trip in the

late afternoon were lost and had to spend the night in the woods,

sleeping on the ground.

When

Oglethorpe’s Regiment reached St. Simon’s, a

better means of communication was necessary; so Oglethorpe

laid out a road which led from the Town Gate of Frederica due east

by the old Burying Ground and across the marsh and Gully Hole

Creek. Here it turned in a southeasterly direction for about two

miles, passing Oglethorpe’s cottage, continuing in this

southeasterly direction through the present Negro settlement known

as Harrington, and touching the eastern marsh of St. Simons, a short

distance north of Black Banks. From this point the road followed

the edge of the marsh to a place which was to become famous as the

site of the Battle of Bloody Marsh. From Bloody Marsh the road

again followed high land and led in a direct line to Fort St.

Simons.

At the point where this Military Road crossed the

present Frederica Road, this marker was erected in 1936 by the

Brunswick Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution as a part of

the community program to celebrate the founding of Fort Frederica.

Pg. 30

Pg. 31

Military Road Near Bloody Marsh

In laying out this Military Road to

connect Fort Frederica and Fort St. Simons, Oglethorpe

planned that “…two men only can march up abreast…” and it was laid

out so as to be “very convenient for ambuscades all the way.”

Oglethorpe engaged the Frederica settlers to cut

the road. They went out on September 25, 1738, “with the General at

their head,” and in three days had completed the task. They did

this work without pay but Oglethorpe rewarded them with

drinks at the Frederica tavern to the extent of a shilling apiece!

Thus this military highway, the location of which played such an

important part in making possible a British victory in the Spanish

Invasion of 1742, was built at a cost of seventeen shillings!

Through the woods the path had to be cut and “through

the marshes rais’d upon a Causeway.” Near Frederica the road

crossed the marsh and Gully Hole Creek where Oglethorpe found

“it was necessary to build a clapper or wooden foot bridge across a

watery savanna near half a mile across and till it was done the

people going to the Fort [Frederica] were…obliged to wade up to

their knees.” This “clapper” was constructed by Samuel Davison,

one of the Frederica settlers, who was paid six pounds for his work.

Communication between these two settlements, an

important contribution toward the happiness of the people, was

further heightened when Oglethorpe established mail service.

William Forrester, the postman, made daily trips between Fort

Frederica and Fort St. Simons, his pay being twelve pence per day.

Another mail messenger carried mail from Frederica to Savannah and

on up to Augusta, so that St. Simons had direct mail service to all

parts of the Colony of Georgia and the other American Colonies, as

well as with Europe.

A small part of the Military Road is still in use, being

that part of Demere Road from the Bloody Marsh monument to its

intersection with Ocean Boulevard. Today, mail is carried over this

part of the old Military Road as it was in the 1740’s, making it one

of the oldest mail routes in Georgia.

Pg. 32

Pg. 33

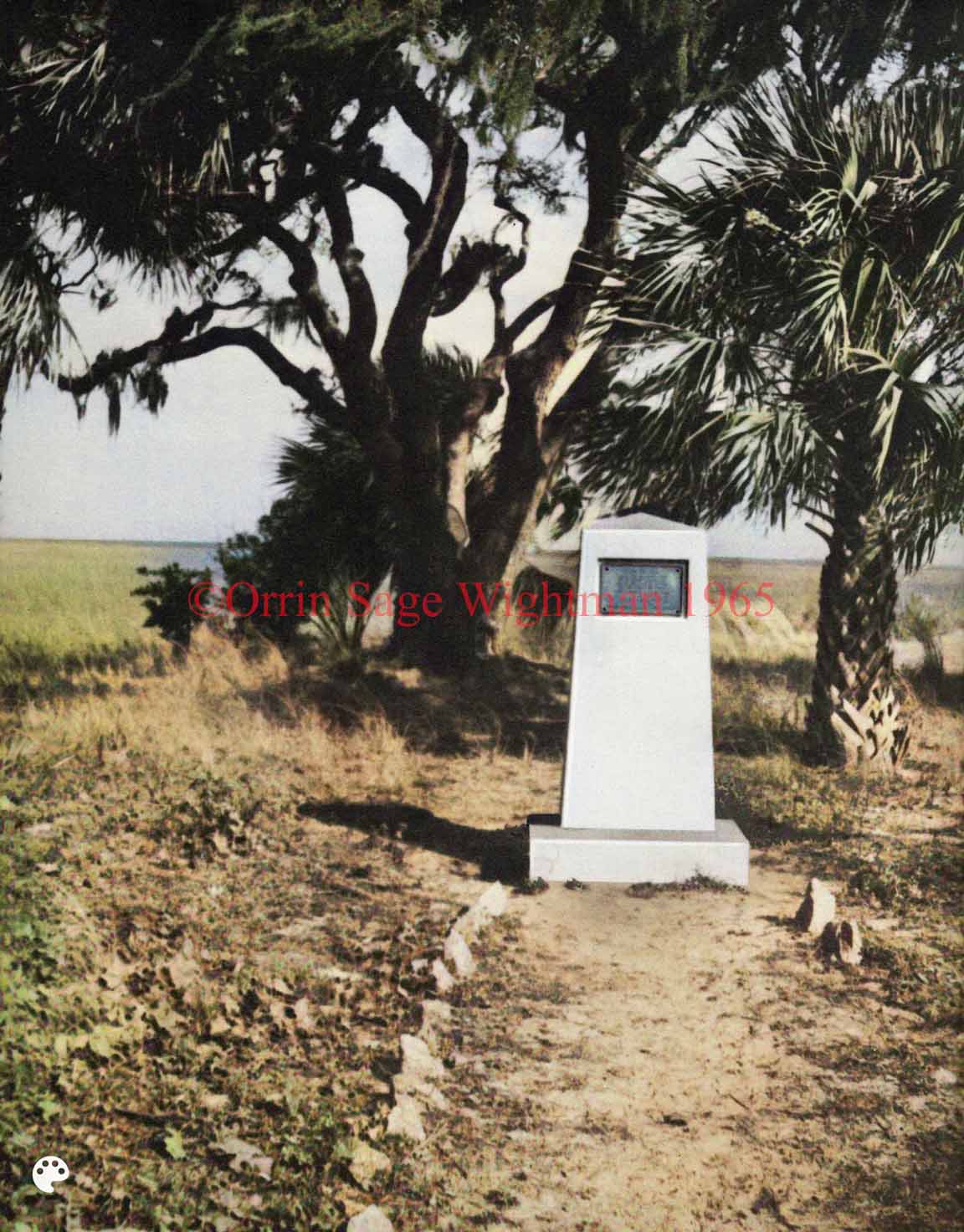

Bloody Marsh Monument

In June, 1742,

Oglethorpe

learned that the Spaniards were assembling a fleet at St.

Augustine. Knowing this meant an attack against Georgia, he sent

messengers asking for assistance. From Savannah came Noble Jones

and the Rangers; from Darien, the Highlanders; and from Carr’s

Fields, the present site of Brunswick and the Hermitage, Capt.

Mark Carr and his Marine Company of Boatmen. These, added to

the soldiers of the Regiment, gave Oglethorpe about nine

hundred men with which to oppose a Spanish Invasion of fifty-one

vessels and three thousand men.

Oglethorpe hoped that the guns of Ft. St. Simons

would be sufficient to prevent the enemy from entering the harbor.

However, the Spaniards succeeded in passing the Fort and sailed up

to Gascoigne Bluff where they landed. Oglethorpe then

abandoned Fort St. Simons and concentrated his entire army at Fort

Frederica, while the Spaniards took possession of Fort St. Simons.

On the morning of July 7th and enemy force of about two

hundred men, sent out as a reconnoitering party, proceeded up the

Military Road to within a mile or so of Frederica. Here an

engagement took place; the enemy retreated with Oglethorpe in

pursuit. About a mile from the Spanish camp Oglethorpe

halted and stationed his forces in a good location while he returned

to Frederica to check on conditions there. The Spaniards then sent

out three hundred Grenadiers to attack the British force. The

British retreated; but, later, fifty of their number formed an

ambuscade where they destroyed the entire Spanish force.

Though the small number lost in this Battle of Bloody

Marsh could not have crippled the enemy force, it did create in

their minds some doubt as to the possibility of victory. By the

clever use of a letter which he wrote to a soldier who had deserted

to the enemy, Oglethorpe succeeded in making the Spaniards

believe that he had superior forces and that assistance would

shortly arrive from Virginia. Thereupon the Spanish commander

hastily withdrew his forces. This was the turning point in the

struggle which made this southeastern section of our country safe

for Britain.

In 1913 this monument was erected on the edge of the

battlefield by The Georgia Society of the Colonial Dames of America

and The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Georgia.

Pg. 34

Pg. 35

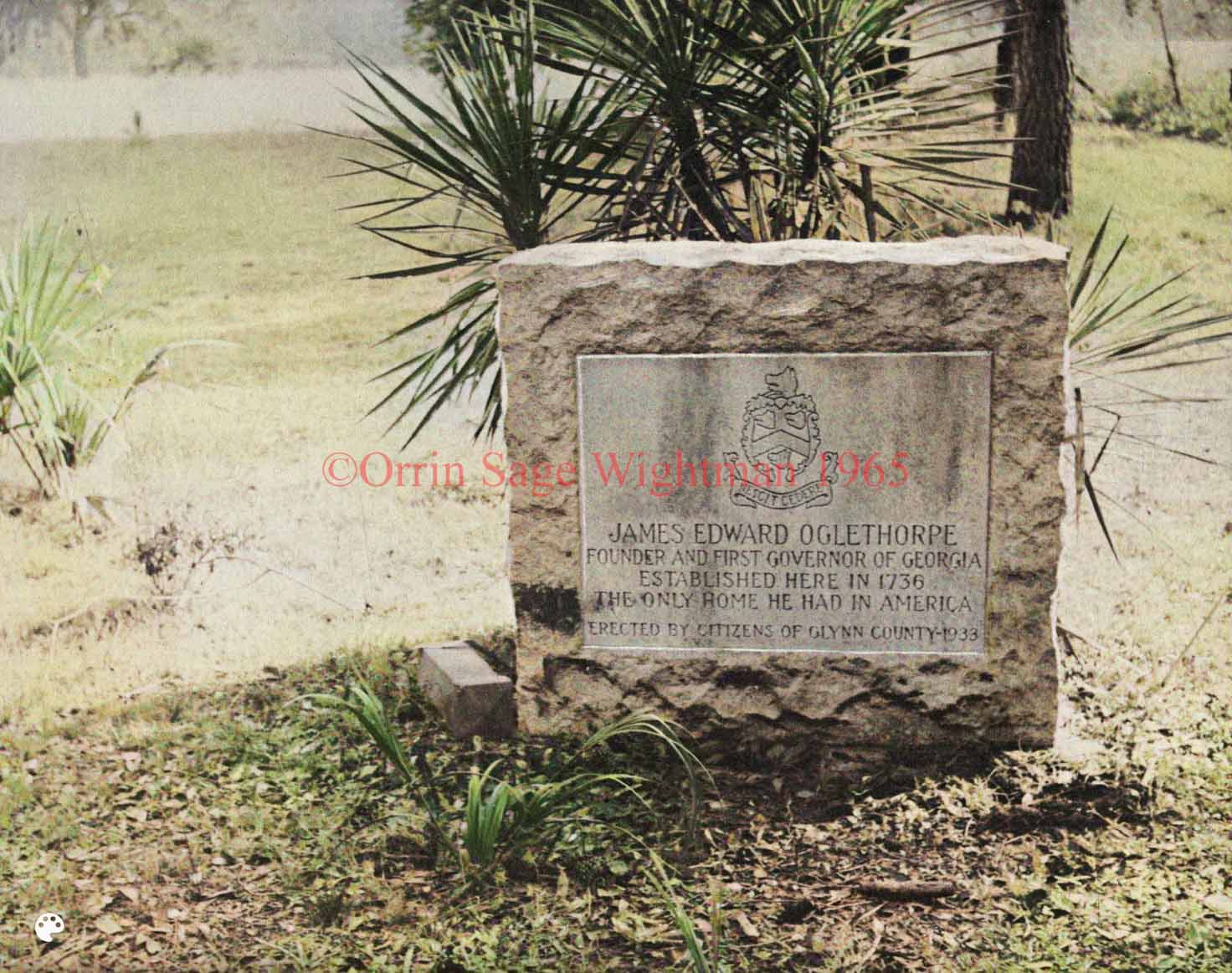

Oglethorpe’s Home

This monument, erected in 1933 by

the citizens of Glynn County to commemorate the Bicentennial of the

founding of the Colony of Georgia, marks the site of the only home

Georgia’s founder had in America.

Oglethorpe’s home, a modest tabby cottage, was

located on a three hundred-acre tract known as “the farm,” sometimes

“the General’s farm.” Though it was called a cottage, it is thought

to have been a story and a half with bedrooms in the half-story. In

1740 Stephens wrote that Oglethorpe was suffering from

“…a lurking Fever that hanged o him for a long Time past had worn

away his Strength very much; so that he indulged himself pretty much

on his Bed, and seldom came down Stairs…”

A visitor to St. Simons in 1743 stated that the

settlement “…at Distance, looks like a neat country Village, where

the Consequences of all the various Industries of an European Farm

are seen. The Master of it has shewn what Application and unabated

Diligence may effect in this Country.” The best description,

however, is from the pen of Thomas Spalding of Sapelo who was

born in this house and stated, “I am only describing a scene

traveled over by infant footsteps and stamped upon my earliest

recollections.” He wrote that, located on the Military Road “just

where the road entered the wood, Gen. Oglethorpe established

his own humble homestead. It consisted of a cottage, a garden, and

an orchard for oranges, figs, and grapes. The house was

overshadowed by oaks of every variety. It looked to the westward

across the prairie…upon the entrenched town and fort, and upon the

beautiful white houses…”

After

Oglethorpe’s return to England this cottage

was perhaps occupied by Major William Horton, who succeeded

as commander of the military forces stationed here and whose home

was on Jekyll Island.

In 1771 this home and fifty acres of land on which it

stood were granted to James Spalding, father of Thomas

Spalding. In 1786 Spalding sold the tract to Thomas

Clubb, whose father had been a soldier in Oglethorpe’s

Regiment; later, it was owned by one Mazoe, too, was

descended from one of Oglethorpe’s soldiers.

Pg. 36

Pg. 37

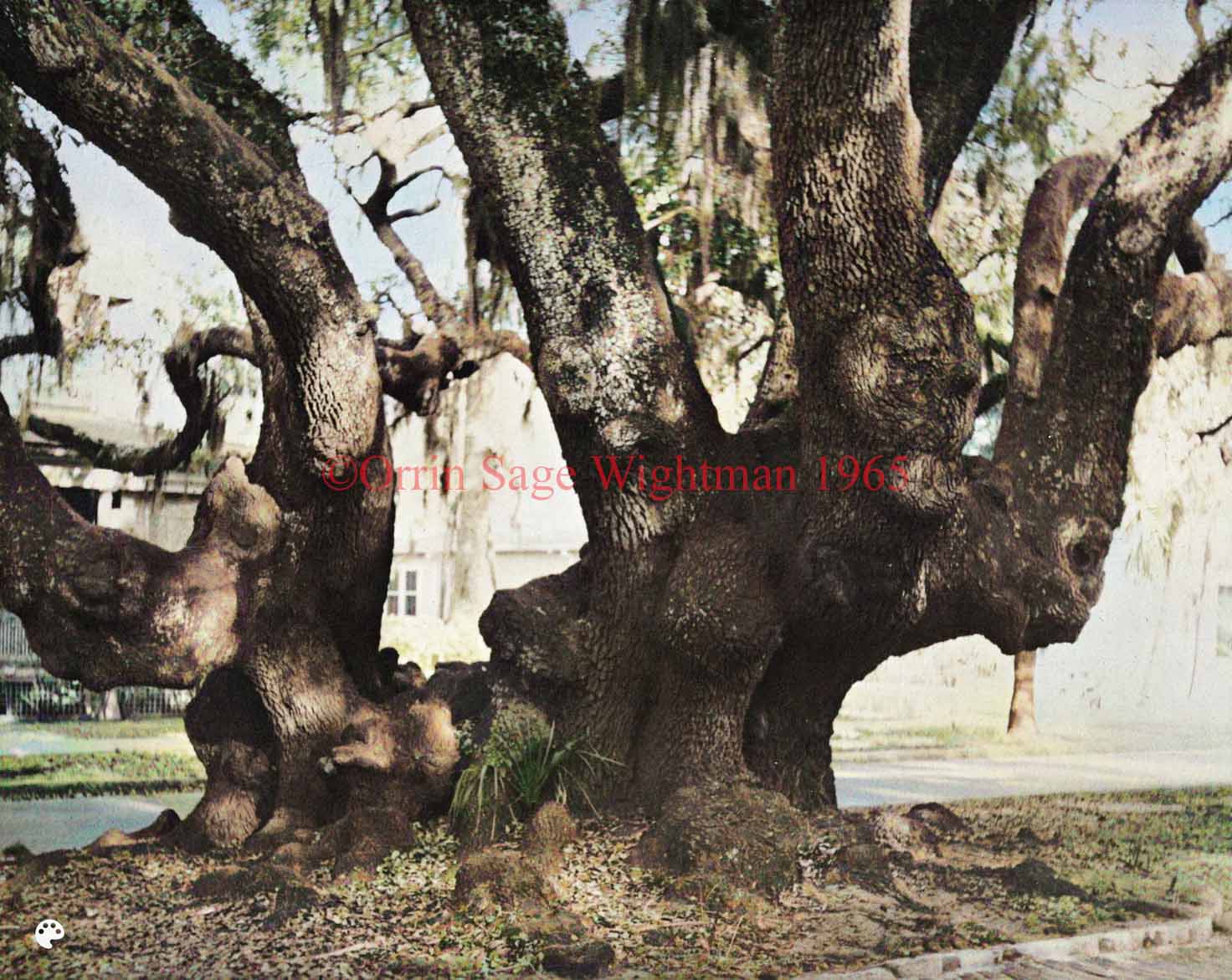

Frederica’s Oaks

When

Oglethorpe first landed

at the bluff which he called Frederica, he gave orders that the

giant live oaks there should be left standing because of their

welcome shade. Though the live oaks which Oglethorpe spared

no longer stand at Frederica, there are others, younger trees, which

still give welcome shade. Indeed, one cannot think of Frederica

without thinking of live oaks, for they are beautiful and numerous.

Those pictured here have grown up on either side of this

winding road near the southeast bastion of the Old Town of Frederica

and they continue in an almost unbroken grove over the area

surrounding Frederica.

Pg. 38

Pg. 39

Frederica’s Old Burying Ground

In this grove of live oaks is

located the old burying ground where lie the bodies of many of those

first settlers who came to Frederica with Oglethorpe. Here

was preached the first funeral at Frederica, which was also the

first funeral of Charles Wesley’s great ministerial career.

The first death among the British settlers here was that

of a young boatman who had been firing the swivel gun in the bow of

the boat as a signal. He overloaded the gun and the explosion

caused a piece of metal to pierce his brain. Charles Wesley

sat up with him that night, ministered to him in his last moments,

and preached his funeral.

John Wesley preached many funerals here. On his

second visit to Frederica he noted in his diary that he buried Mr. Germain in the evening. A few days later he was with the

surgeon, Dr. Henry Lascelles, in his last illness, made his

will, and several days later buried him in the evening. A year

after, the son, Henry Lascelles, the only other member of the

family in Georgia “…was unfortunately Drown’d being in the River

with many Other Boys…and Buried by his Father…”

Some of these vaults of brick or of tabby are to be seen

in Frederica’s old burying ground, but there are no markers to tell

whose body lies in any of the graves.

Pg. 40

Pg. 41

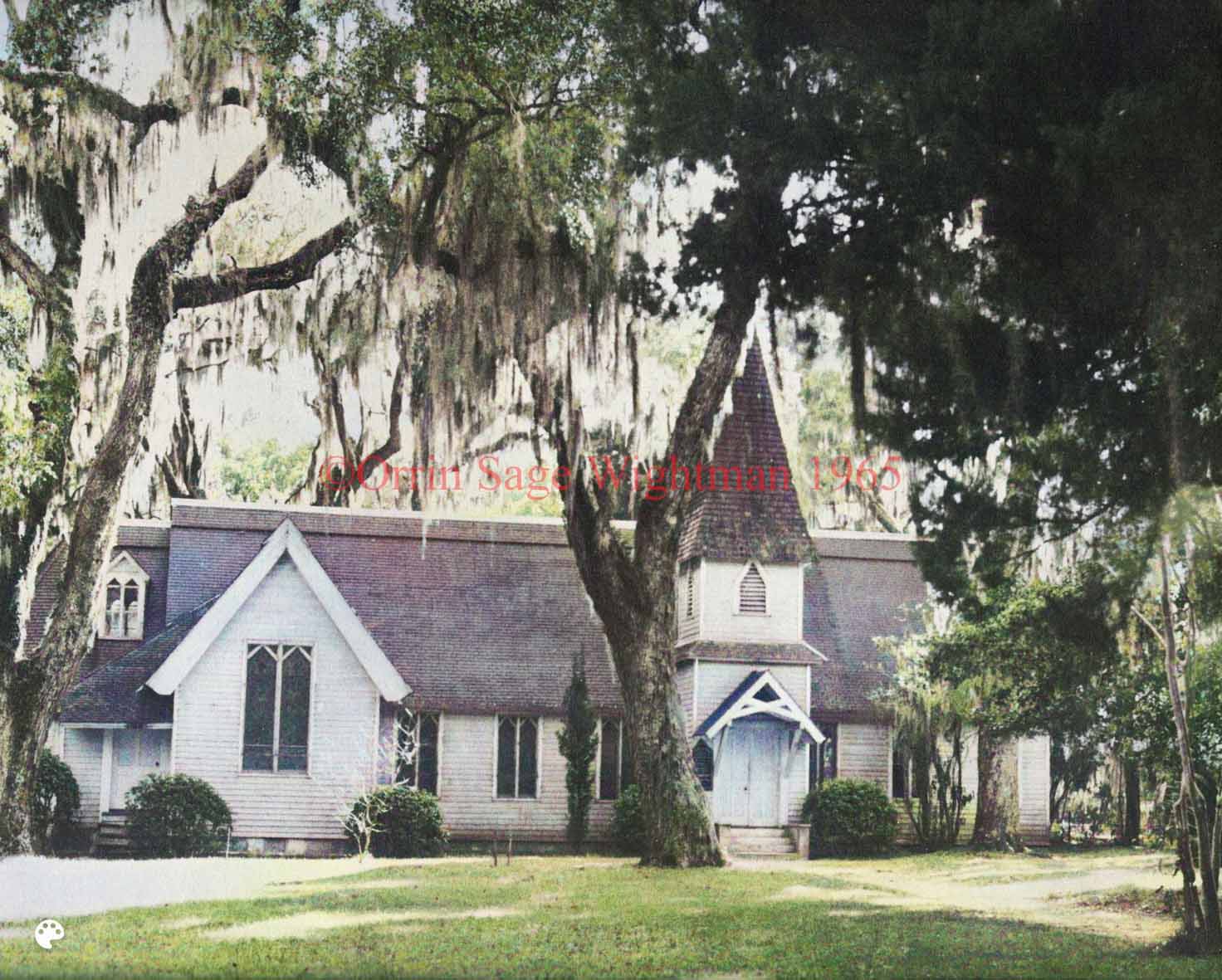

Christ Church Frederica

In the group which accompanied

Oglethorpe on his 1736 voyage to Georgia, brining the Frederica

settlers, were John and Charles Wesley, founders of

Methodism.

These

Wesley brothers came as missionaries of the

Church of England, their salaries being paid by the Society for

Propagating the Gospel in Foreign Parts. John Wesley had

charge of the religious affairs of the Colony and was stationed

primarily at Savannah. Charles Wesley, who had received holy

orders just before sailing from England, came to Frederica as Oglethorpe’s secretary and as Secretary for Indian Affairs, in

addition to his duties as minister for the Frederica settlers.

Charles Wesley was at Frederica little more than

two months and John Wesley made five trips here. While at

Frederica the Wesleys preached in the storehouse within the

confines of Fort Frederica and in the open under the great oaks.

After the Wesleys returned to England, others took their

place.

In 1808, lands which had formerly been garden lots of

the old Town of Frederica were granted to Christ Church and a

building was erected here by the plantation owners of St. Simons.

During the Civil War St. Simons was occupied by Federal forces and

Negro troops desecrated the church, destroying the altar, burning

the pews, and breaking the windows. After the war, though there was

no house of worship, the parishoners [sic] kept their church alive

by meeting in their homes with the services of lay readers and

occasional visiting ministers from Brunswick or Savannah.

This building was erected in 1884 by

Anson Green

Phelps Dodge, Jr., in memory of his bride, Ellen Ada Phelps

Dodge, who had died in India. Returning to St. Simons where his

family had business interests, Mr. Dodge decided that the

rebuilding of this ruined church would be a fitting memorial for his

wife whose body was placed in a brick vault under the chancel.

Mr. Dodge then took holy orders and became the rector of this

church which he had built, serving it until his death in 1898.

Pg. 42

Pg. 43

Couper Tombstones, Christ Church

Cemetery

There are many interesting and

impressive tombstones in Christ Church Cemetery, but none is more

beautiful than these of Italian marble which mark the graves of John Couper; his wife,

Rebecca (Maxwell) Couper, and

their daughter, Isabella Hamilton (Couper) Bartow.

Mr. Couper, a native of Scotland, came to America

in 1775, living in Savannah and in Liberty County before coming to

St. Simons in 1796. Here, he located at the North End of the Island

at a place known as Cannon’s Point, which had been granted more than

half a century earlier to one of the first settlers of the Town of

Frederica, Daniel Cannon. Cannon and his two sons,

Joseph and Daniel, were the carpenters who built some of

the first houses at Frederica. The Cannons left St. Simons

in 1741 and moved to Charleston, where they continued to build good

houses.

At Cannon’s Point

John Couper developed

one of the finest plantations in the South. Though Sea Island

cotton was his staple crop, he was interested in the diversification

of his crops; and, among other things, he brought in dates fro

Persia and olives from France. Thomas Jefferson interested

him in olives and a quarter of a century after their importation

there were 250 bearing trees in the Cannon’s Point olive grove.

These trees were killed in a freeze in 1886 and, today, the only

reminder of this grove is the landing on Jones Creek, which is still

known as “Olive Grove Landing.”

In the lower left-hand corner of this picture we see the

dead stump of one of Mr. Couper’s old live trees. From this

stump came the tree which stands at the left. Today, that, too, is

gone, but from its root came another—the third generation of Mr.

Couper’s olive trees grow over his grave. A proper monument to

a great planter!

Pg. 44

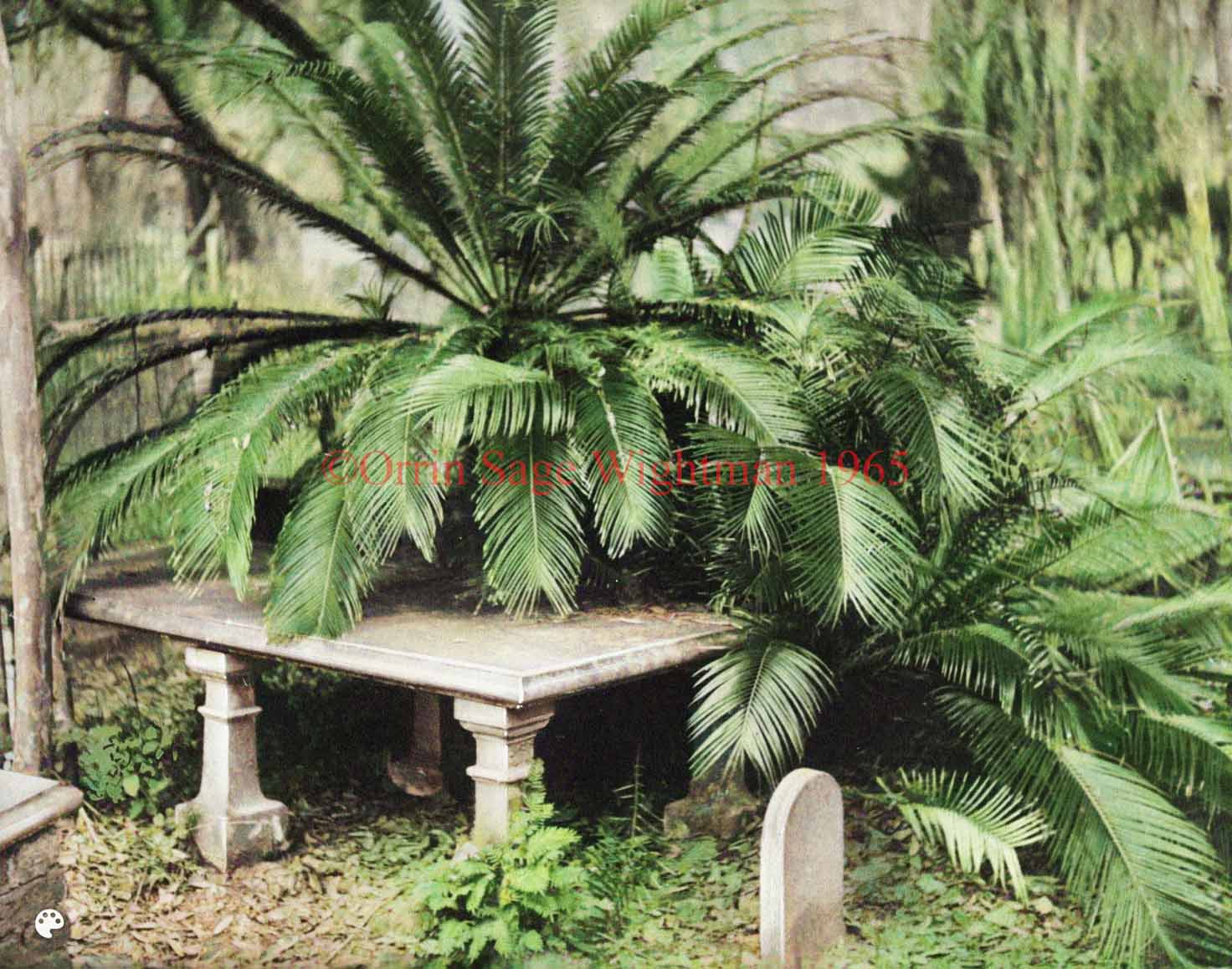

Pg. 45

Armstrong Tomb, Christ Church

Cemetery

The

Armstrong family had

lived in the American Colonies before the Revolutionary War, but

during that struggle they remained loyal to the Mother Country and

refugeed in the Bahama Islands. While living there, William

Armstrong died and his widow Mrs. Ann Armstrong, whose

tombstone is pictured here, returned to this land and settled on St.

Simons Island.

It is said that she brought from the Bahamas to St.

Simons the sago palm Cycas revoluta which, in time, was

planted in every local plantation garden. Indeed, if one should try

to find just one plant which would typify such a garden, it could

well be the sago palm. Mrs. Armstrong died in 1816 and a

sago palm has been planted at her grave.

The

Armstrongs married into the other plantation

families here. The oldest son of Mrs. Ann Armstrong, William, had married in the Bahamas. His daughter,

Ann,

married Benjamin Franklin Cater of Kelvin Grove Plantation

and their only child, Ann Armstrong Cater, married James

Postell.

Mrs. Armstrong’s youngest child, Margaret,

married Alexander Campbell Wylly, who lived at the Village,

and whose children married into the families of the Spaldings

of Sapelo Island, the Coupers of Cannon’s Point, and the Frasers of Darien.

Perhaps there is no one person who lived on St. Simons

Island during the Plantation Era who was connected with as many

families as was Mrs. Ann Armstrong, whose beautiful marble

tombstone, with its lovely sago palm, is pictured here.

Pg. 46

Pg. 47

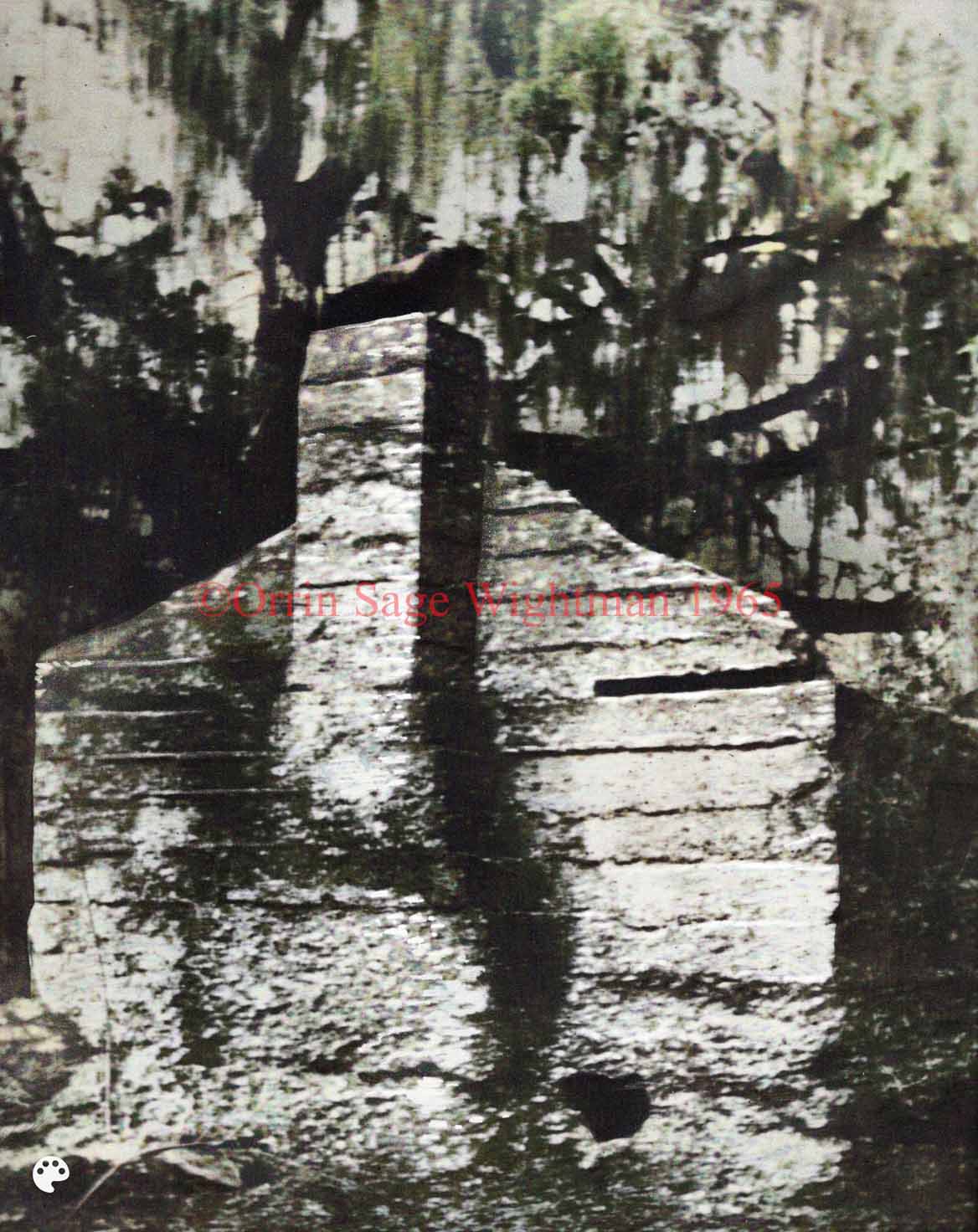

Hazzard Vault, Christ Church Cemetery

Built in 1813, this

Hazzard

family vault has been in ruins since the Civil War, when it was

desecrated by Negro troops of the United States Army stationed on

St. Simons Island at that time.

Even though St. Simons Island and the waters surrounding

it were occupied by Federal forces, Capt. William Miles Hazzard

of the Confederate States Army led a group of nine soldiers in a

successful raid against Federal installations on St. Simons, burning

the coaling wharf at Gascoigne Bluff and causing other damage. In

addition to Capt. Hazzard who was the son of Col. William

Wigg Hazzard of West Point Plantation, several members of this

small group of Confederates lived on St. Simons and they knew how to

move around the island without being detected. So successful were

they in accomplishing their objectives in spite of overwhelming

odds, that they were cited for bravery.

While on this raid

Capt. Hazzard saw the damage

which had been done to his family vault at Christ Church and

addressed a communication to the officer in command of the Federal

forces:

I have more than once

been informed…that the graves of our family and a friend had been

desecrated by your forces…This rumor I could not believe, as the

custom, even of the savage, has been to respect the home of the

dead. But the sight which I now behold convinces me of the truth of

the report I shuddered to think of…let me tell you, sir, that beside

these graves I swear by heaven to avenge their desecration. If it

is honorable to disturb the dead, I shall consider it an honor, and

will make it my ambition to disturb your living. I fancy, sir, the

voice of the departed issues from their desecrated homes exclaiming

that such a nation may truly say to corruption, thou art my father;

to dishonor, thou art my mother; to vandalism, thou art my ambition.

William Miles Hazzard

The commander of the Federal

forces, finding this note attached to a stick and placed in a

prominent position in the road, sent it to his commanding officer

with the acknowledgement that “the complaint of the writer is but

too true” and that the Negro troops “committed grave outrages,

firing upon the church, pulpit, gravestones, etc.”

Pg. 48

Pg. 49

John Wylly’s Tombstone

This broken shaft, emblematic of

early death, marks the grave of John Armstrong Wylly, who was

killed Dec. 3, 1838, by Dr. Thomas Fuller Hazzard. Bad

feeling had existed for some time between these men and, of course,

there are many tales about the cause. It is known that they did

have differences about the boundary line between their property.

The Wylly family owned the German Village tract, generally

called “The Village,” on the eastern shore of St. Simons, while the

Hazzards lived on the western shore of the Island, with their

lands joining in a north-south line.

In those days plantation owners used dams of earth to

mark the boundaries of their property. Erected by slave labor these

earthen dams, several feet high and as many feet wide, are to be

found all over St. Simons. The Wyllys built their earthen

dam on the line they claimed, while the Hazzards constructed

a dam on what they claimed was the correct line. Today, these

Hazzard and Wylly dams stills stand, in some places being

only a few feet apart.

Several months before the fatal encounter,

Dr.

Hazzard challenged Mr. Wylly to a duel; Mr. Wylly

refused to fight, whereupon Dr. Hazzard “posted him” by

attaching a notice to a tree telling of Mr. Wylly’s refusal

to accept the challenge. A letter describing this stated this

notice was posted on a pine tree “as the road turns in to

Frederica…Poor tree…at the rising of the sun the next morning was

found prostrate with the ground and cut up into billets and this

work of noble revenge was done by some fairy friend of Mr. W’s—for

no human creature knows anything about it…”

The death of

Mr. Wylly took place in Brunswick

where these men happened to meet on the steps of the Oglethorpe

House. After exchanging a few words, Mr. Wylly struck

Dr.

Hazzard with a cane. Friends intervened and separated them.

However, a short time afterward they chanced to meet in the entry of

the Oglethorpe House, when Mr. Wylly spat in Dr. Hazzard’s

face; whereupon Dr. Hazzard pulled a pistol and shot Mr.

Wylly, the bullet passing directly through the heart. Dr.

Hazzard was arrested and charged with manslaughter, but the jury

failed to convict him.

The inscription on the tomb shown in this picture states

that John Wylly “fell victim to his generous courage.”

Pg. 50

Pg. 51

Pink Chapel, West Point Plantation

Following the death of

John

Armstrong Wylly, the two Hazzard families, those of Dr. Thomas Fuller Hazzard of Pike’s Bluff Plantation and his

brother, Col. William Wigg Hazzard of West Point Plantation,

found themselves cut off from the other plantation families of St.

Simons Island.

The

Wyllys were one of the old families of the

Island and were connected by blood or marriage, with almost every

other plantation family in the area. John Armstrong Wylly’s

older brother had married the daughter of Thomas Spalding of

Sapelo Island, while his younger sister had married James

Hamilton Couper of Cannon’s Point. Another of his sisters had

married into the Fraser family and the Frasers had

married into the Couper and Demere families; in

addition, Wylly’s first cousin had married Benjamin F.

Cater of Kelvin Grove Plantation. With this solid wall of

relatives and family connections to take the part of the dead man,

the Hazzard families were practically ostracized.

Rather than attend and worship at Christ Church,

Frederica, in the hostile atmosphere of their critical neighbors,

the Hazzards erected their own family chapel at West Point

Plantation. Built of tabby and only large enough for the use of the

people of their own plantations, it still stands, though in ruins.

A beautiful pink lichen,

Chiodecton sanguineum,

which grows only in dense shade on old walls and tress, now colors

the old tabby ruins of the Hazzard Chapel, giving it the name

Pink Chapel.

Pg. 52

Pg. 53

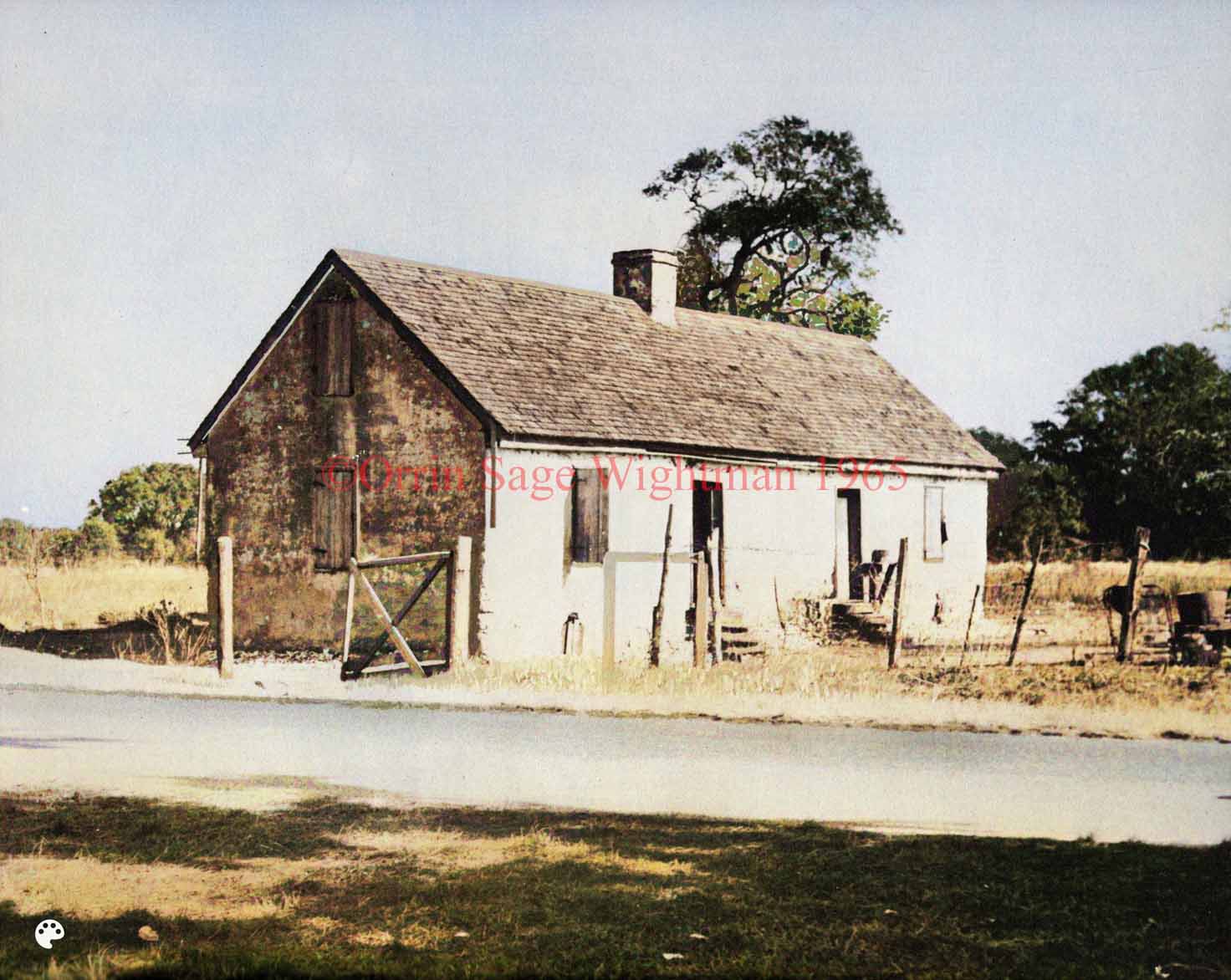

Slave Cabin, West Point Plantation

The tabby ruin shown here was one

of the slave cabins of West Point Plantation, the home of Col.

William Wigg Hazzard.

These

Hazzards were from South Carolina and the

first to move to St. Simons Island was Major William Hazzard

of the Revolutionary War. Major Hazzard died in 1819, but

his two sons continued to live here and made their homes on

adjoining plantations. Col. William Wigg Hazzard of the War

of 1812 and of the Mexican War, with his wife Mary Blake (Miles)

Hazzard, made his home at West Point, while his brother, Dr.

Thomas Fuller Hazzard, and his wife Sarah Turner (Richardson)

Hazzard, lived at Pike’s Bluff. Both of these men died about

the time of the Civil War; but Col. Hazzard’s son, Capt.

William Miles Hazzard of the Confederate States Army, continued

to live at West Point until “after the War.”

This picture, taken in 1936, has preserved for the

record a tabby cabin with a tabby chimney. Generally, these tabby

houses had brick chimneys since it was easier to build a chimney of

brick than to change the shape and size of the forms for the chimney

with the pouring of each layer of tabby.

This cabin would have been the sort used to house a

small Negro family. Larger cabins had the chimney in the middle of

the house with a fireplace on either side. Soon after this picture

was made, the tree in the background was blown over, finishing the

ruin of the cabin.

Pg. 54

Pg. 55

Date Palm at Cannon’s Point

Date palms were among the plants

imported by John Couper for his Cannon’s Point Plantation.

They were brought from Bussora, Persia, and for many years produced

ripe fruit. This palm now growing at Cannon’s Point is not the

original. The old tree died in 1885 and from its root came a shoot

which grew into this palm. Standing near the eastern entrance to

the Couper residence, it is a silent reminder of days gone

by.

When

John Couper moved to St. Simons in 1796 to

make his home, he occupied the modest story-and-a-half house which

had been built by Daniel Cannon in 1738. Later, Mr.

Couper built a large two-and-a-half story house, the handsomest

plantation house on St. Simons, and here they Coupers

dispensed lavish hospitality. Their guests came from every part of

this country and from Europe.

Aaron Burr, vice-president of the United States,

came to St. Simons in 1804 after the duel which resulted in the

death of Alexander Hamilton. During his five-week stay at

Butler Point, he went over to visit the Coupers. In his

letters to his daughter Burr described life “in the

benevolent home of Mr. Couper.” In 1828, Capt. Basil Hall

of the British Navy, with his wife and daughter, spent some days

here. Capt. Hall’s Travels in North America describes

the operation of the plantation, while Mrs. Hall’s letters

(edited by Una Pope Hennessy and published under the title,

The Aristocratic Journey) give a picture of the social life.

Fanny Kemble, noted English actress and wife of Pierce

Butler of Butler Point Plantation, had nothing but kind words

for the Coupers, though little else that she saw in Georgia

met with her approval! Sir Charles Lyell, president of the

Geological Society of London, with Lady Lyell, was here in

1846. In A Second Visit to the United States of North America,

Lyell gives a vivid picture of life at the Couper

home.

Frederika Bremer, Swedish novelist and

abolitionist, made a pleasant visit here in 1851 and records that

fact in Homes of the New World.

After the Civil War the Cannon’s Point property passed

into the possession of the Shadman family and in 1890 the

house was struck by lightening and burned.

Pg. 56

Pg. 57

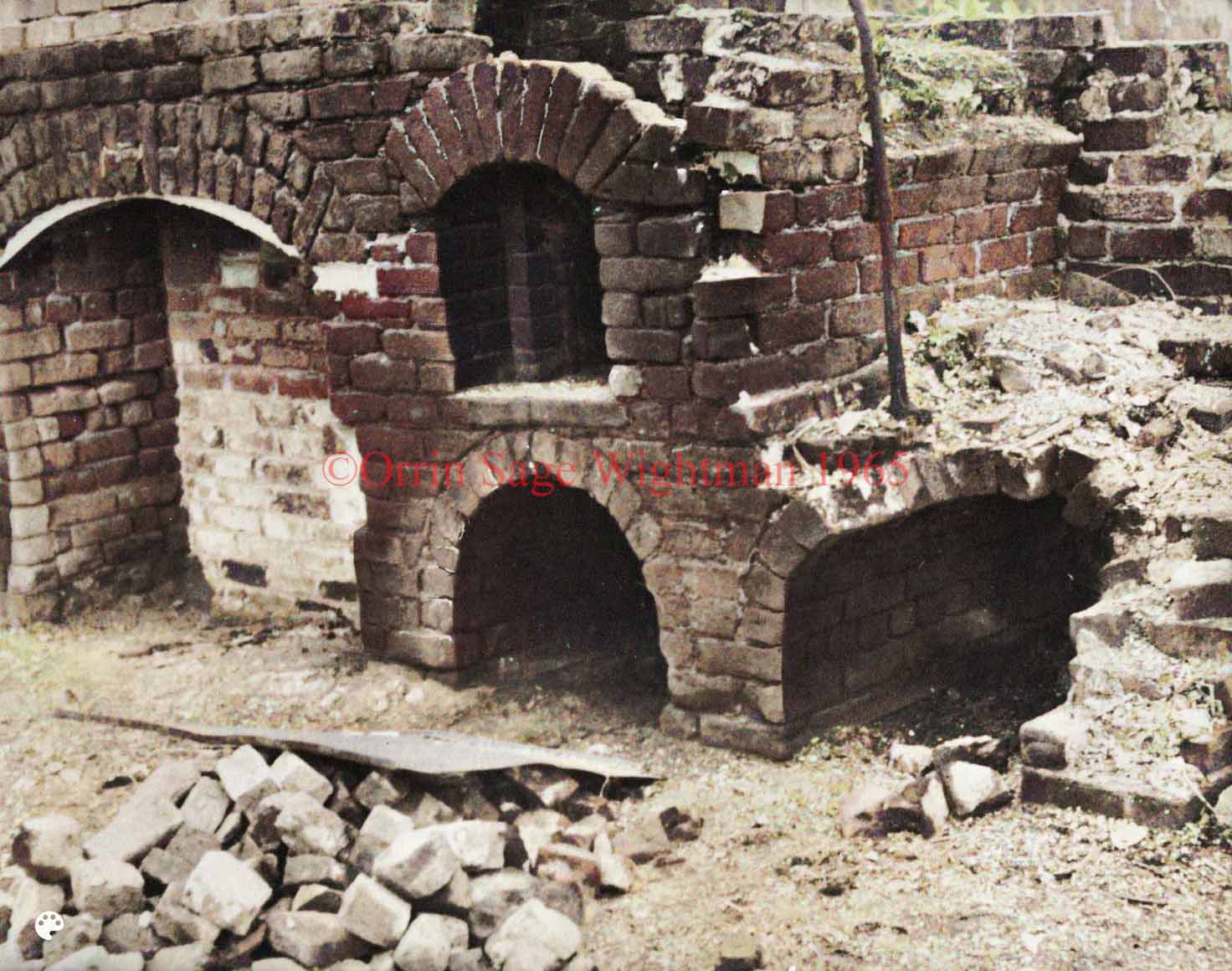

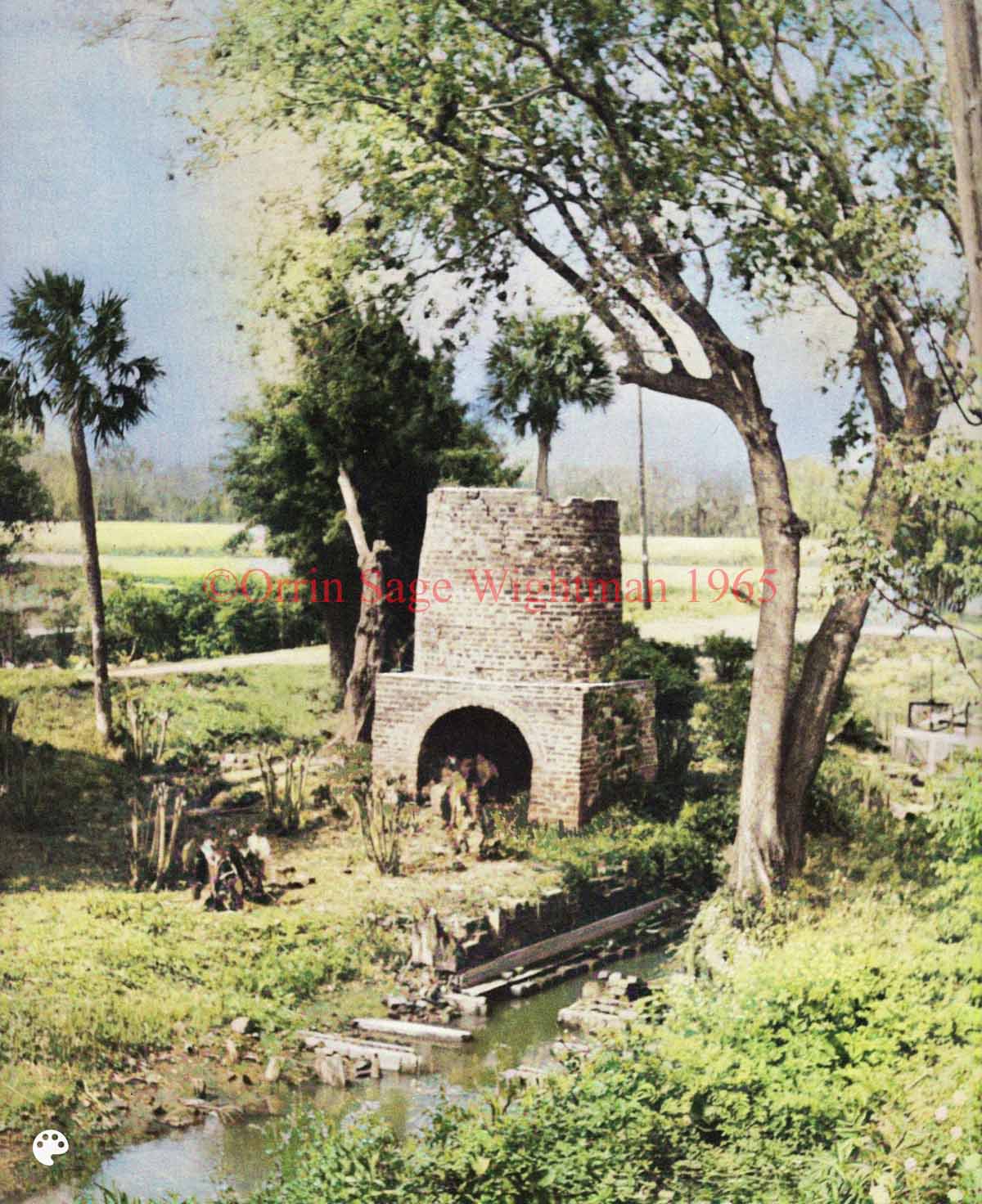

Ruins of the Kitchen, Cannon’s Point

Plantation

In this fireplace and in these

ovens of the old kitchen at Cannon’s Point, was prepared the food

served to the members of the Couper family and their guests.

As was customary on Southern Plantations, this kitchen was in a

separate building and a short distance from the plantation

residence, an arrangement which removed from the residence the noise

and confusion of preparing the meals and, in addition, lessened the

danger of fire.

From this kitchen the food was carried to the “Big

House,” where a door at ground level gave entrance to a small room

with stairs leading up to the butler’s pantry, adjacent to the

dining room on the main floor.

One of the famous cooks who presided over the Cannon’s

Point kitchen was Cupidon. Cupidon had been the slave

of the Marquis de Montalet, a refugee from San Domingo,

residing at the North End of Sapelo Island at the former home of de Chapedelaine, which he called “La Chalet”—a name which the

Negroes corrupted to “Chocolate.”

Montalet spent his days at La Chalet immersed in

his dreams and his memories. He and his friend, Chevalier de la

Horne, early in the morning and late in the afternoon, walked

through the live oak forests of Sapelo with a pig on a leash hunting

truffles! Oh, that one day they might find them!

When the

Marquis died, his will decreed that Cupidon should be freed, along with his wife,

Venus, and

their son, Hercules. When old Venus heard the news,

she was worried: “Nobody ter look atter us; no house ter lib in;

what we gwine do?”

Cupidon said: “Don’ you wrooy; we gwine ter St.

Simons ter lib wid Mr. John Couper!” And so they came to

Cannon’s Point and adopted Mr. Couper as their master.

Cupidon presided over the kitchen and trained many others in the

culinary arts of which he was master.

Pg. 58

Pg. 59

Slave Cabin, Butler Point

This slave cabin was one of a row

of cabins standing at Hampton, or Butler Point, when Fanny Kemble

was here during the winter of 1838-39.

In December, 1838,

Pierce Butler came to Georgia

to take over the management of these estates from Roswell King,

who was moving to North Georgia, where he founded the town of

Roswell. On this trip he was accompanied by his wife, Fanny

Kemble, and their two children, Sarah, aged three years,

and Fanny, aged seven months.

Arriving at the close of the year 1838, they went first

to the rice plantation in the delta of the Altamaha River, Butler

Island, where they stayed about two months after which they moved to

Butler Point. Here, on St. Simons, they remained until the middle

of April before returning to Philadelphia. This four-month stay was

the only trip Fanny Kemble ever made to Georgia.

While here she kept a journal of the daily happenings on

the plantation. Published in 1863 as Journal of a Residence on a

Georgia Plantation 1838-39, it throbs and burns with a fine

hatred of slavery, and is said to have caused more criticism of the

South than any book that was ever written except Uncle Tom’s

Cabin.

Though

Fanny Kemble was extremely critical of all

she saw that man had done, she reveled in the beauties of Nature.

From the house at Butler Point she looked out “on these green woods,

this unfettered river, and sunny sky” and was fascinated by the

beauty of the scene.

While walking in the woods she stood still to admire the

beauty of the shrubbery and felt that “the wood paths…were really

more beautiful than the most perfect arrangement of artificial

planting in an English park.” The beauty of the sky brought forth

high praise and she decided that “Italy and Claud Lorraine

may go hang themselves together!” “The moonlight slept on the broad

river,” she wrote, and, all in all, “It was lovely.”

Pg. 60

Pg. 61

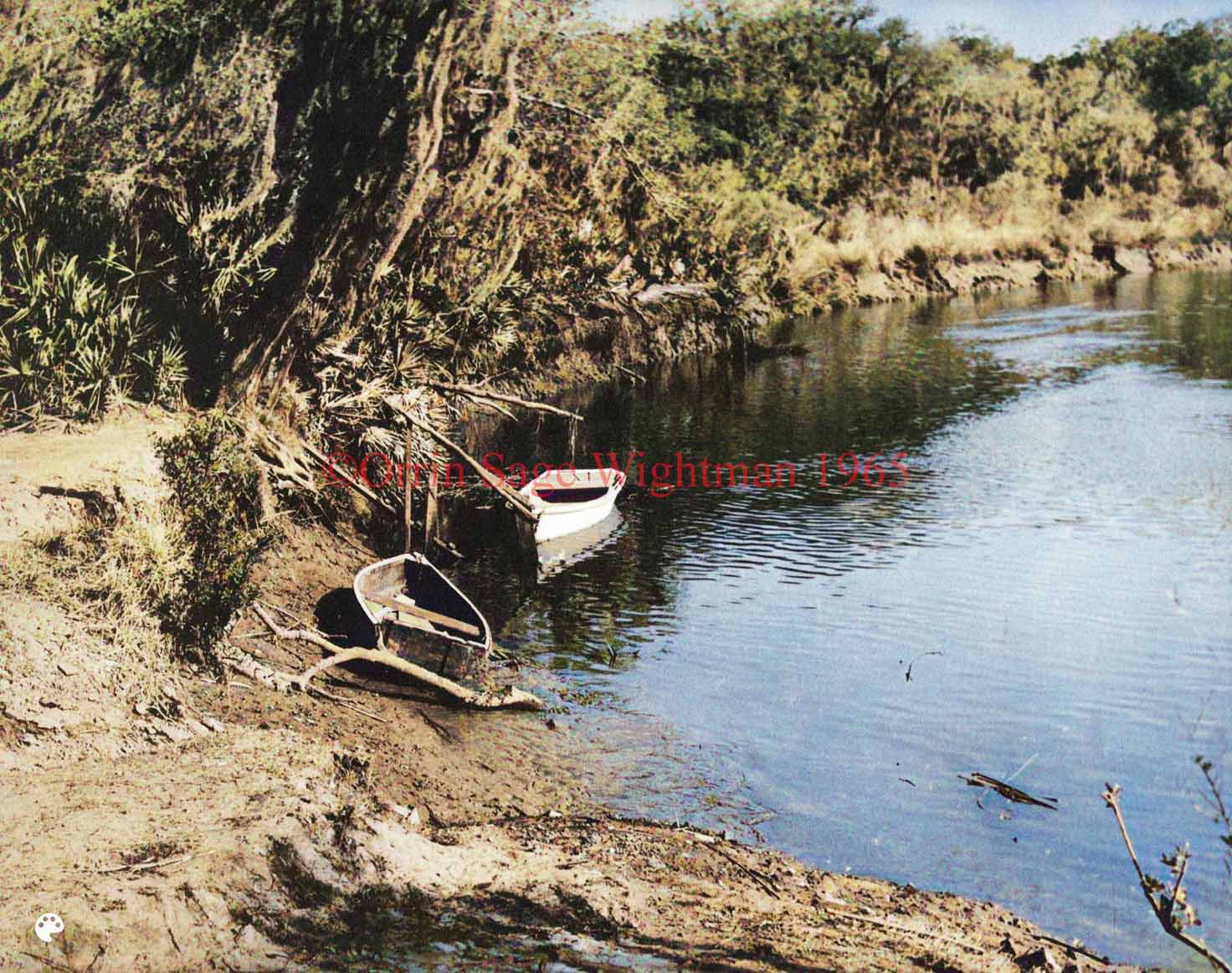

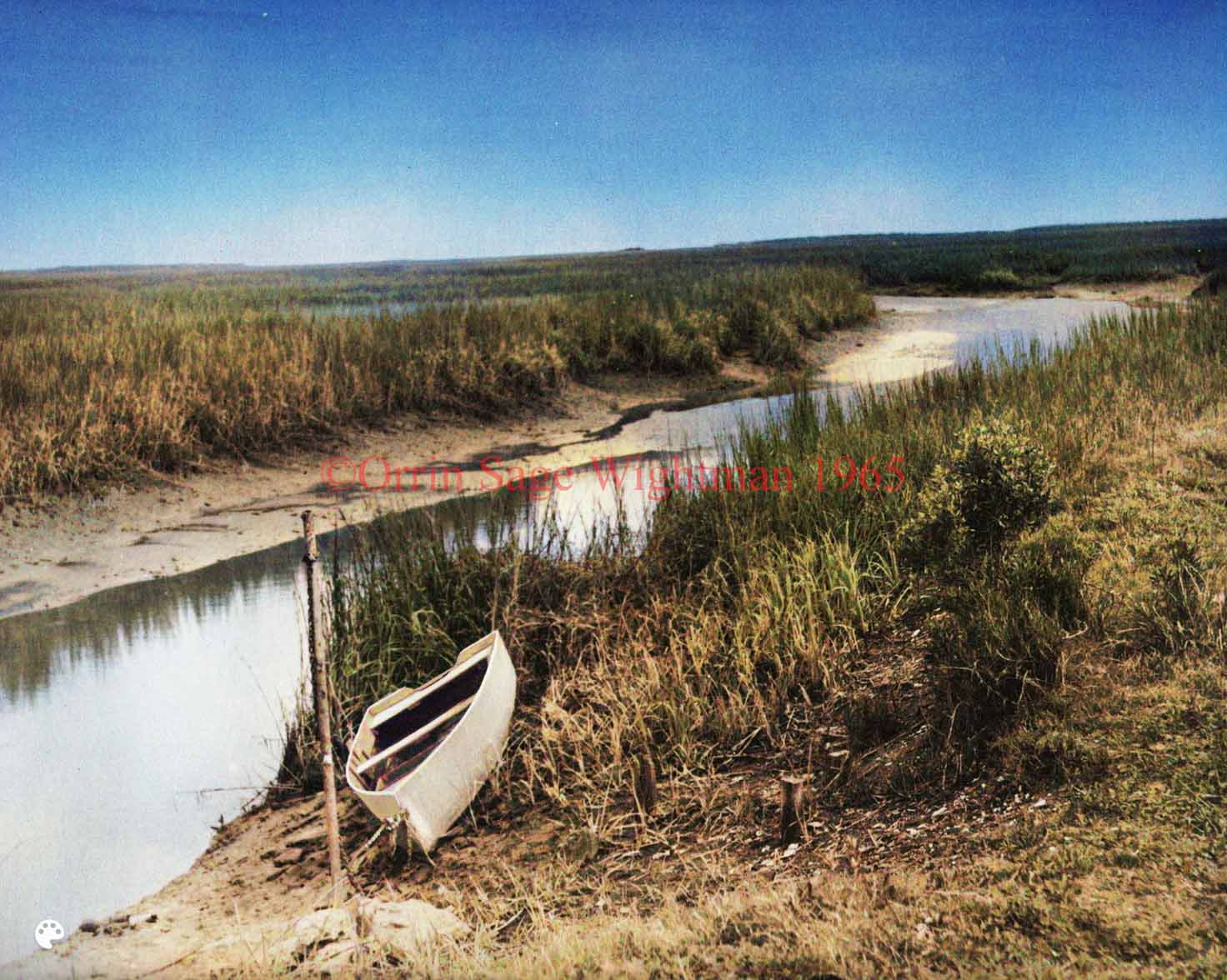

Hampton River at Butler Point

When

Oglethorpe fortified

St. Simons Island he stationed soldiers of his regiment at various

bluffs so that they might give the alarm if the enemy attempted to

land at any of these places. Nineteen soldiers received grants of

fifty acres each at the northwest point of the island and here they

lived with their families. They called the place Newhampton, but

soon it was shortened to Hampton; even that name is lost today,

though the river which flows past is still known as Hampton River.

The invention of the cotton gin brought about the

development of great cotton plantations throughout this section and

this tract of land was acquired by Major Pierce Butler.

Major Butler was the younger son of Sir William Butler

and was descended from the Dukes of Ormond. He came to America in

1766 as the Major of the 29th British Regiment and was stationed in

the New England Colonies. After his marriage in 1771 to Mary

(“Polly”) Middleton, daughter of Col. Thomas Middleton of

South Carolina, he resigned his commission in the British Army and

took up life as a South Carolina planter.

During the Revolutionary War he became an officer in the

American Army and later was prominent in South Carolina politics,

being a member from that State to the Convention which framed the

Constitution of the United States and a signer of that document.

Major Butler was then elected Senator from South Carolina and

sat in that first Senate of the United States, which met in New York

City. When the Capital was moved to Philadelphia, he moved with it;

and from then on, Philadelphia was home.

In his will,

Major Butler stipulated that his

Georgia estates should become the property of his two grandson,

provided they would take the name Butler. These grandsons,

John Mease and Pierce Butler Mease, were the sons of

his daughter Sarah, who had married Dr. James Mease of

Philadelphia. This grandson, Pierce Butler Mease, now

Pierce Butler, married the noted English actress and violent

abolitionist, Fanny Kemble.

Pg. 62

Pg. 63

Mackintosh Vaults

Here, in the deep forest of

Sinclair Plantation, are two brick vaults which entombed the bodies

of John Lachlan and Sarah, the only children of Major William Mackintosh of the Revolutionary War.

This tract of land was first granted to

Archibald

Sinclair, tithingman of the South Ward of the Town of

Frederica. Sinclair built here a tabby house which became

his plantation home. After the disbanding of Oglethorpe’s

Regiment, St. Simons Island was practically deserted and Sinclair

abandoned his plantation, which in 1765 was granted to Donald

Forbes as bounty land for his services in Oglethorpe’s

Regiment. Forbes sold these lands to Gen. Lachlan

McIntosh of Revolutionary fame, whose son, Major William

Mackintosh, lived and died in the old tabby house. Major

Mackintosh’s body lies near those of his children whose vaults

are pictured here. The marker for his grave was erected in 1940 by

the Brunswick Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution. Later,

this tract became the property of Major Pierce Butler of

Butler Point Plantation.

In 1832, the plantation masters of St. Simons formed an

organization, known as The Agricultural and Sporting Club of St.

Simons Island, who used Sinclair’s old tabby home as their

Club House. This Club held regular meetings and, in addition,

celebrated special anniversaries, such as the Centennial of the

Founding of Fort Frederica. For this event they invited the members

of the Camden Hunt Club “and their ladies” to be special guests.

At meetings of The Agricultural and Sporting Club,

papers were read by the members which were published later in the

agricultural periodicals of the day, and included John Couper’s

talk on The Culture of the Olive Tree; Thomas Spalding’s

papers on The Mode of Constructing Tabby Buildings and The

Origin of Sea Island Cotton, and Dr. Thomas Fuller Hazzard’s

paper on The Culture of Flowers as Conducive to Health, Pleasure,

and Rational Amusement. The Club House had a well-stocked

library, as well as facilities for quoits and billiards, and also

was used as an informal meeting place where deer drives and fishing

excursions were arranged.

Pg. 64

Pg. 65

Slave Cabins of Hamilton Plantation

This plantation, located at

Gascoigne Bluff, was the property of James Hamilton of

Scotland who came to America with his friend John Couper

about the time of the Revolutionary War. Here he made his home in a

two-story tabby house, later removing to Philadelphia where he died

in 1829.

This property then came in to the

Corbin family

through the marriage of Agnes Rebecca Hamilton to Francis

P. Corbin. The Corbins lived in Paris where the

daughters married into the French nobility. However, they

considered themselves citizens of the State of Georgia. When their

State cast her lot with the Confederate States of America, the son,

Richard W. Corbin, was not content “in these stern times,

with a horizon bounded by the Bois de Boulogne and the Jockey Club”;

but felt that he must “act as it becomes a man who wishes to earn

the respect of his countrymen” and offered his services to his

country. He slipped into the port of Wilmington, N.C., on a

blockade runner, made his way to Virginia and became Aide on Gen.

Field’s staff of Gen. Longstreet’s Corps, and gave

devoted service to the cause of the Confederacy. With Lee’s

surrender, he returned to France, secure in the knowledge he had not

been found wanting when duty called.

In 1874 a lumber mill operated by

Urbanus Dart of

Brunswick and his sons was erected at the lower end of Gascoigne

Bluff. In 1876 the Dodge, Meigs Co., later the Hilton, Dodge Lumber

Co., operated a ill at the upper end of the Bluff, occupying the

site of Hamilton Plantation and utilizing the plantation buildings,

including the tabby barn, the slave cabins and the tabby house which

had been the Hamilton residence. Vessels from every part of

the world lined the wharves to load cargoes of long-leaf yellow pine

and cypress lumber until the mills ceased to operate and were

dismantled in 1903.

Hamilton Plantation was purchased in 1927 by

Mr.

and Mrs. Eugene W. Lewis of Detroit, Michigan, who made it

their winter home. In 1949 the South Georgia Conference of the

Methodist Church established here the Methodist Center,

Epworth-By-The-Sea.

These old slave cabins are now the home of the Cassina

Garden Club. Its members have carefully preserved the original

lines and character of the cabins and are developing an old

plantation garden.

Pg. 66

Pg. 67

Ebo Landing

The importation of Negro slaves

into the English Colonies began in 1619 when they were brought into

Virginia. Founded as a military colony, Georgia prohibited Negro

slavery since it was desired that all men brought into the Colony

should bear arms and no Negro slave was ever allowed a gun. This

was the only one of Britain’s Colonies in North America to prohibit

slavery and for the first twenty years of the life of the Colony

there were no Negroes in Georgia.

In 1798, Georgia prohibited the importation of Negroes

direct from Africa and about a decade later in the United States

passed similar laws. From that time all Negroes from Africa were

smuggled into the country and kept in hiding until they could be

disposed of to plantation owners.

The winding creeks and waterways of Coastal Georgia

afforded ideal landing places for such cargoes, just as in the

previous century they had harbored pirates, and a century later they

were to provide safety for bootleggers. Ebo Landing on Dunbar Creek

was one of the best of these. Sheltered from view of traffic in

Frederica River by the dense growth on Hawkins Island, Ebo offered

these slave traders a haven for their illicit merchandise.

Tradition says that a group of Ebo Negroes who were being held here

walked into the water and drowned themselves rather than be slaves,

saying “The water brought us here; the water will take us away.”

The Eboes were described as having “a sickly yellow

tinge in their complexion, jaundiced eyes, and prognathous faces

like baboons.” The women were said “to be diligent but the men

lazy, despondent and prone to suicide.” Slave traders avoided

cargoes of these Ebo Negroes and freighted them only when no others

were available.

So, be it fact or fiction, the story of Ebo Landing fits

into the known characteristics of this tribe and the name Ebo has

been attached to this site for a century and a half. In the olden

days no Negro would drop a hook to fish at Ebo. It was “ha’nted”!

Pg. 68

Pg. 69

Ruins of Retreat Plantation House

The first of the lands which became

Retreat Plantation in 1736 when Oglethorpe stationed John

Humble here and appointed him the first pilot for this harbor.

Humble’s home stood about where the Sea Island Golf Club

house now stands.

Later, these lands were granted to

John Clubb as

bounty for his service in Oglethorpe’s Regiment. Clubb

made his home here and in 1786 sold the property to Thomas

Spalding, son of James Spalding, of Ashantilly,

Perthshire, Scotland. The Spaldings lived at Retreat for

some years and then Thomas Spalding, having purchased Sapelo

Island, sold Retreat to Major William Page, who with his

wife, Hannah Timmons, had come to St. Simons to visit their

friend, Major Pierce Butler, of Butler Point. On this visit

which lasted a year, their only living child, all the others having

died young, grew healthy and strong, so they decided to make St.

Simons their home. This last child, Anna Matilda Page, grew

to womanhood at Retreat and was married to Thomas Butler King

of Massachusetts.

As

Mr. King was prominent in public life, he was

away from home much of the time, so that the management of the

plantation was in Mrs. King’s hands. The account books in

her handwriting record the receipts from the sale of the cotton, the

expenses of the family, and many interesting items connected with

the management of the plantation. In addition to running the

plantation, Mrs. King reared a family of nine children—five

boys and four girls. As the family grew, a four-room, two-story

addition was built on to the residence and used for the boys and

their tutor. These houses were destroyed by fire about 1905 and

nothing remains today except a brick chimney and some of the

foundation of the residence.

Retreat remained in the possession of the

King

family until 1926, when it was purchased by the Sea Island Company

for a Golf Course.

Pg. 70

Pg. 71

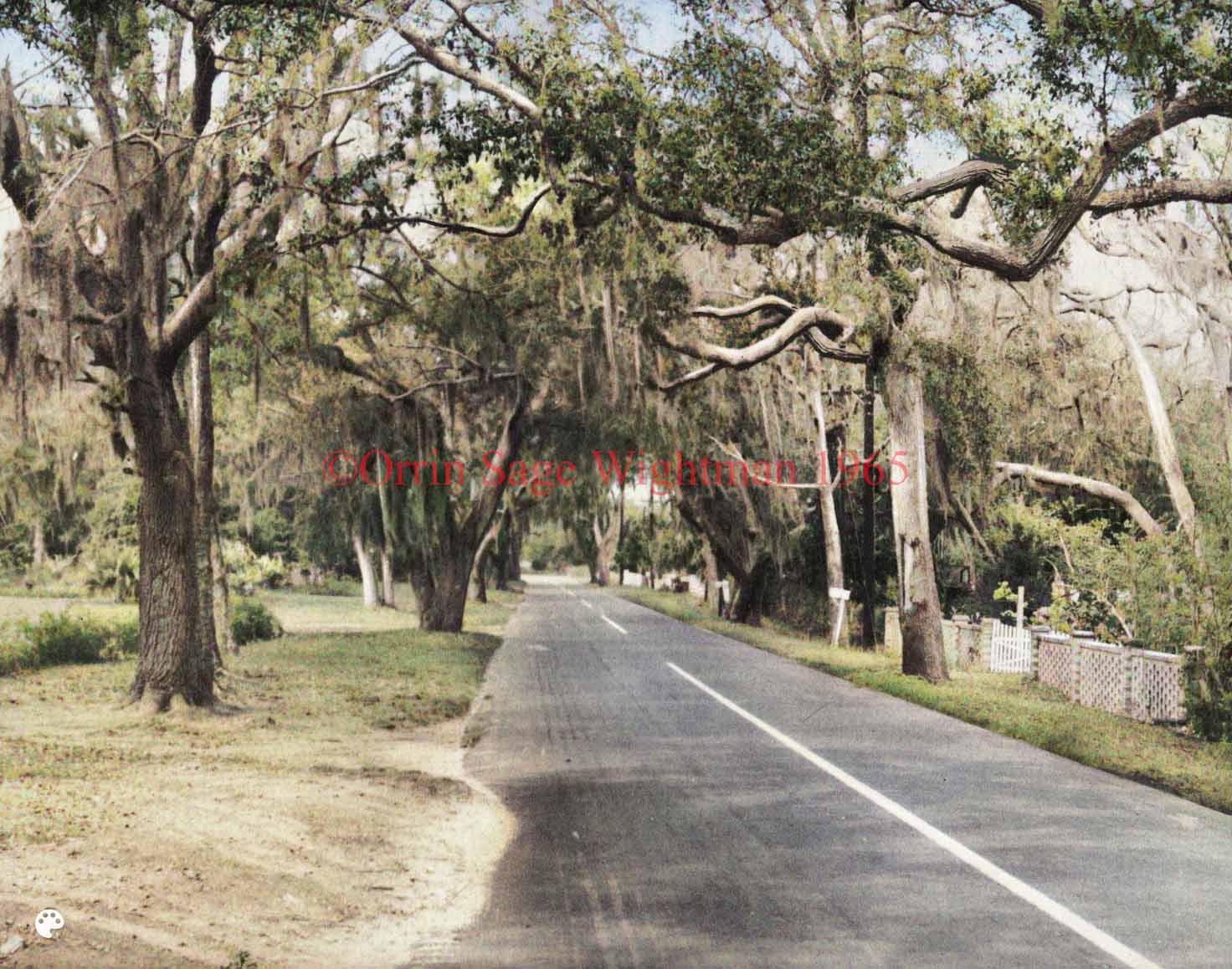

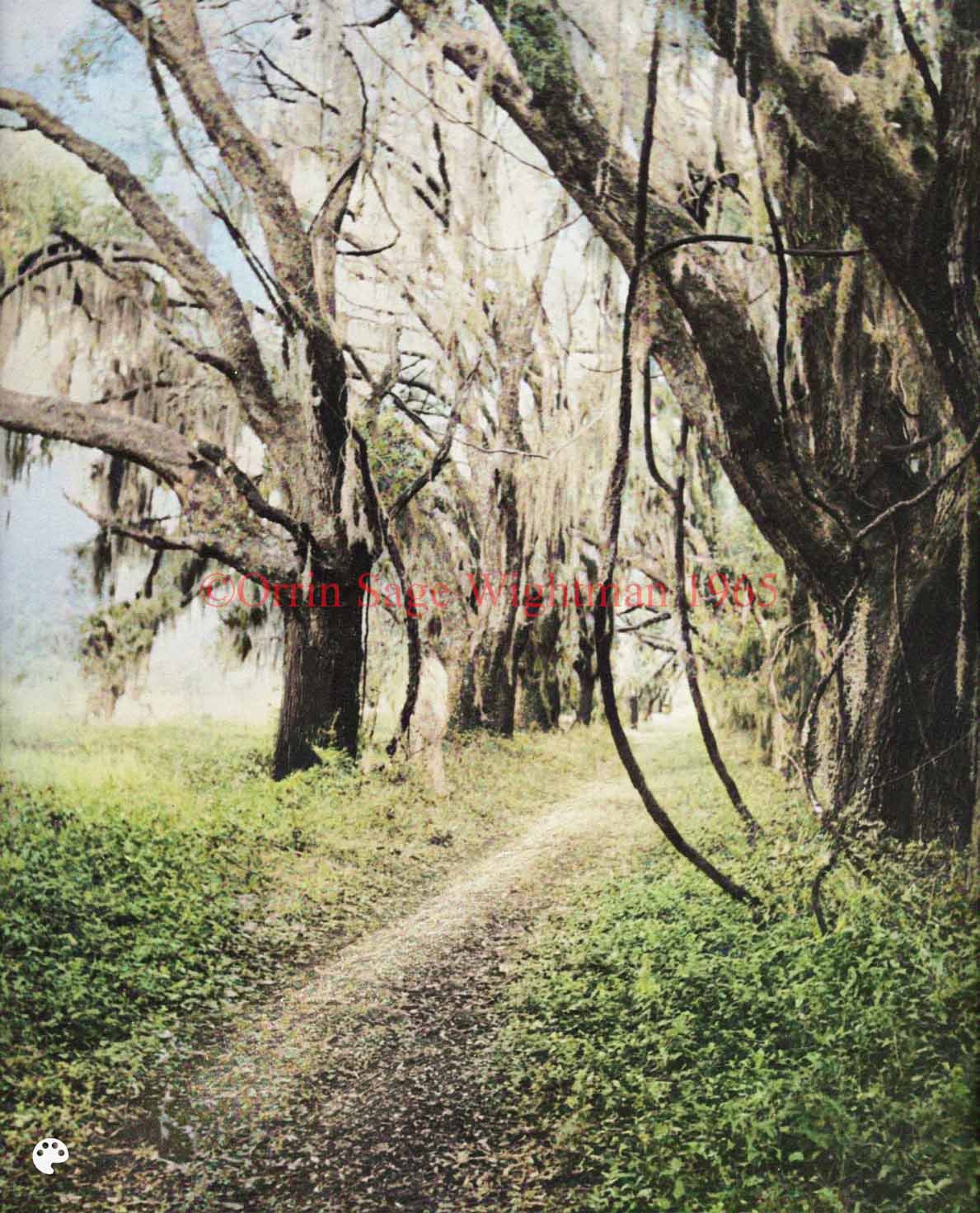

Retreat Avenue

This beautiful avenue of live oak

trees Quercus virens formed the entrance to Retreat

Plantation. In Plantation Days the road was wide enough for

carriages; but, for its use today, a paved road on either side of

the avenue leaves the trees, with the old plantation road, just as

they were “before the War.”

Among the

King family letters in the Southern

Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina Library at

Chapel Hill, there is one written by Anna Matilda (Page) King,

mistress of Retreat Plantation, to her teen-age son, Henry Lord

Page King, who was away at school, in which she tells of the

building of this road and the planting of these trees.

Work such as the building of roads was planned for the

seasons when the crops had been gathered and the slaves could be

spared from work in the fields.

In Georgia, men were required to do road work in the

militia district in which they resided in order to keep the public

roads in good condition. Mr. King obtained permission to use

The Retreat slaves in building this new road and let it suffice for

the road work required of them.

Writing on December 1, 1848,

Mrs. King announced

that a new road to New Field was being made and that all the field

hands had been at work on it. She said, “It goes in a direct line

from Sukey’s house and shortens the distance by a quarter of

a mile.”

Her letter continued: “The labor is great for there

were several low places to be filled up and once continuous mass of

palmetto roots to cut through.” She added that trees were being set

out “all along the road and it will take 500 trees to go the

distance.”

Time, and the relentless hand of man, have spared only

this short stretch of the century-old oaks of Retreat Avenue.

Pg. 72

Pg. 73

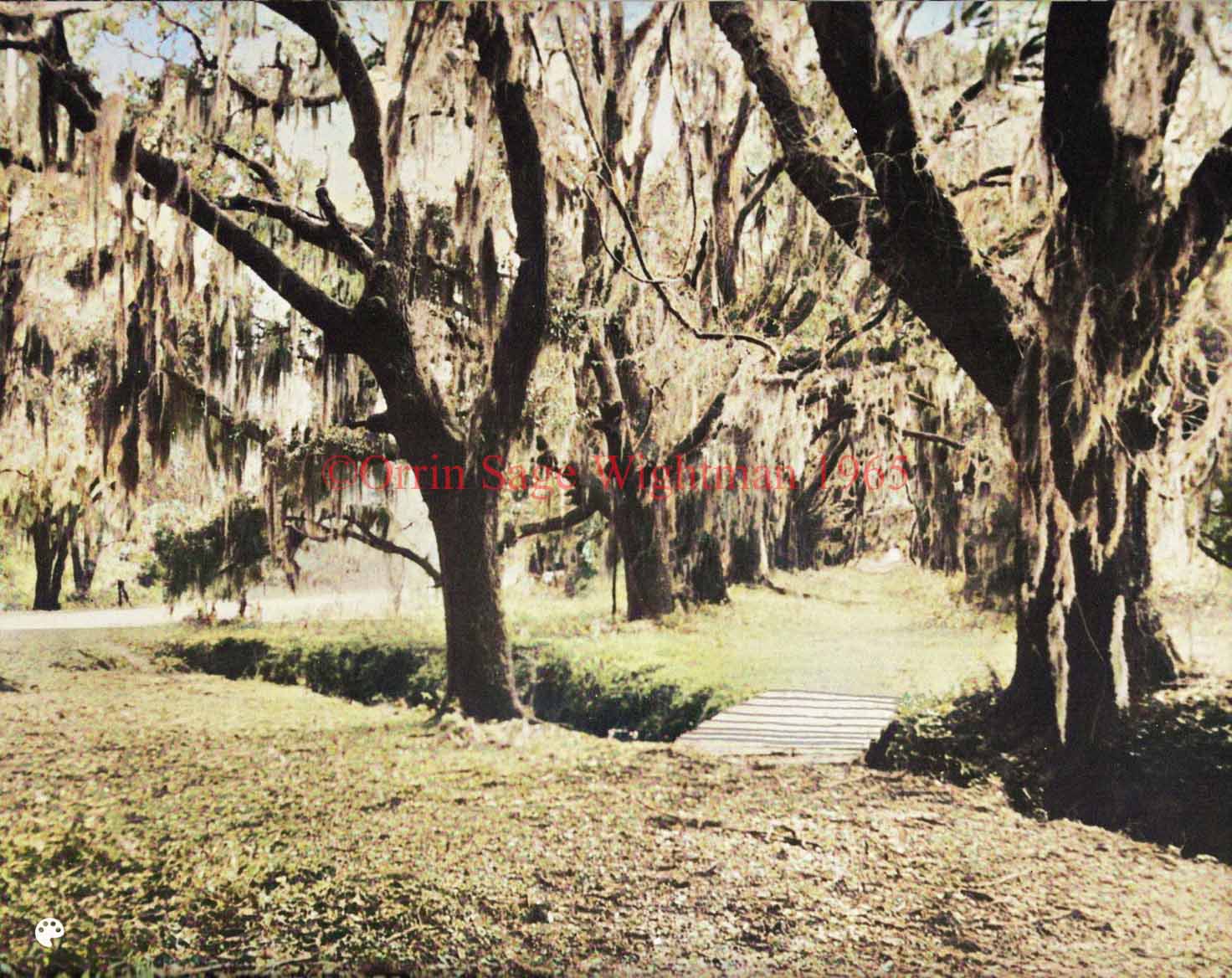

Retreat Avenue at Baldwin’s Ditch

This view of Retreat Avenue,

beautiful and serene, arouses no thought of the busy outside world;

yet, there is something here which tell another story.

Thomas Butler King of Retreat was a national

figure. After a term in the Georgia Legislature, he was elected to

the United States Congress, where he was chairman of the Committee

on Naval Affairs. While serving in this capacity, he instituted a

program for modernizing the Navy. He advocated setting up bureaus

so as to develop specialists in every branch—naval architecture,

armaments, etc.—and, under his plan, in 1842 the Navy was

reorganized practically as it is today. His progressive measures

were acclaimed by business men over the country and by the Navy.

In 1849 he was sent to California as the personal agent

of President Zachary Taylor to report on the advisability of

admitting California to the Union. A year later President Fillmore named him Collector of the Port of San Francisco. This

appointment brought about his second trip to California when he was

accompanied by his eldest son, Thomas Butler King, Jr., who

served as a clerk in the Customs House.

Mr. King’s work was along the line of internal

improvements, one of his projects being the building of a railroad

from Brunswick to the Gulf of Mexico. As a part of this project

there was to be a canal from the Altamaha River to the Port of

Brunswick. Boston interest bought stock in the railroad and canal

and the engineer sent down to make the survey was Loammi Baldwin,

a Yale graduate and son of a Revolutionary General, also an

engineer, but remembered best as the man who propagated the Baldwin apple.

Loammi Baldwin had worked on the Bunker Hill

monument, had designed and built the dry docks at Charlestown,

Mass., and Norfolk, Va., and came to be known as “The Father of

Civil Engineering in America.” While Baldwin was here to

make the survey for the railroad and the canal, Mr. King

utilized his services in surveying the drainage ditch for Retreat,

which is shown in the foreground of this picture. Dug in 1836 by

slave labor, this ditch still serves its purpose as do Baldwin’s

famous works elsewhere.

Pg. 74

Pg. 75

Retreat Hospital

This ten-room, tabby building was

the slave hospital of Retreat Plantation. The rooms on the ground

floor were used for the women, the second floor for the men, while

the attic rooms were occupied by the two nurses, who lived here.

The rooms were twelve by fifteen feet, each room having a fireplace

and two windows. The staircase was in the wide hall in the middle

of the house.

It was customary on all plantations in the South for the

slave hospital to be built near the residence of the plantation

owner. Of all the plantation buildings at Retreat the hospital was

nearest to the master’s home, the sick Negroes being the special

interest of the mistress of the plantation, who made frequent trips

to the hospital to supervise their care.

In

Mrs. King’s plantation record book she

itemized the births and deaths of the slaves, as well as causes of

illness. A list of twenty-eight children and two adults had measles

in 1856. A notation at the bottom of the page gave the names of

five who were “infants and did not take it.”

In recording the deaths of her servants

Mrs. King

paid tribute to them. The record of Hannah’s death is a fine

example: “My good and faithful servant Hannah after years of